When people asked psychology professor Paul Bloom what new project he was working on, he would reply “empathy” – adding the rider that he was “against” it. This, he was to discover, was like “being against kittens, a view considered so outlandish that it can’t be serious”. The remark sets the tone for his latest book. Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion is a deliberately maverick work – astringent, provocative, often witty and unabashedly against a prevailing culture that places so high a premium on the virtue of empathy that at least 1,500 books available through Amazon apparently have a version of the word in their title.

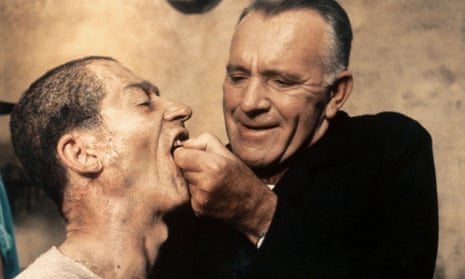

The basis of Bloom’s argument is that fine feelings, like fine words, butter no parsnips. Feeling your pain is all well and good but not necessarily the best trigger of an effective moral response. Indeed, he argues that an ability to intuit another’s feelings might well be an aid to some dubious moral behaviour. A low score on the empathy index is commonly believed to be a feature of psychopathy, but many psychopaths are supremely able to feel as others feel, which is why they make good torturers.

Bloom cites the character of O’Brien in Orwell’s 1984, whose capacity to discern his victim’s responses is exquisitely refined: “‘You are afraid,’ said O’Brien, watching his face, ‘that in another moment something is going to break. Your especial fear is that it will be your backbone. You have a vivid mental picture of the vertebrae snapping apart and the spinal fluid dripping out of them. That is what you are thinking, is it not, Winston?’” It is through this facility that O’Brien can divine Winston Smith’s greatest dread (a fear he himself has never articulated), rats, and deploy it to destroy him.

Bloom, it should be said, is not in favour of an indifferent heartlessness. Indeed, his trenchant stand against empathy is an attempt to encourage us to think more accurately and more effectively about our relationship to our moral terms. He pins his colours to the mast of rational compassion rather than empathy, and it is a central tenet of the book’s argument – I think a correct one – that there exists a confusion in people’s minds about the meaning of the two terms.

The mirroring of another’s anguish is not, Bloom would claim, the principal source of kindness, a quality that he is supremely in favour of. It is not empathy, he argues, that leads one to spring to the rescue of a drowning child or necessarily give to charity. Indeed, an over-identified response to another’s parlous situation could well lead to paralysis and inaction or, in causing an additional personal distress, only add to the general sum of human woe.

Worse still, “kindness motivated by empathy often has bad effects”. On that note he is interesting on the subject of parenting, pointing out that “good parenting involves coping with the short-term suffering of your child”. An over-identification with one’s child’s unhappiness can be disabling to both parent and child (it might be a longer-term benefit to your child to bear for a time the nasty cold of the swimming bath or the dentist’s chair). He points out that a doctor who felt their patient’s pain would be unlikely to be able to do their job – picture a surgeon empathising with your cancer as she cuts out your tumour. Nor, a rather different point, is empathy what we necessarily want. I recall the indignation I felt when having had my wallet stolen I was subjected to a “victim’s visit” from the local crime unit – a patronising and irritating substitute, I felt, for anyone actually tracking down my lost credit cards.

Bloom is especially vocal on the need for a rational objectivity in political and social policy and the dangers attendant on decisions prompted by empathy because it is “innumerate and biased”. Empathy, he suggests, narrows our focus in a self-regarding way – there is sustained evidence that we empathise more with those that either resemble us or those we find attractive. The picture of five-year-old Omran Daqneesh, pulled from the rubble in Aleppo, prompted widespread breast-beating, but Bloom would be sceptical of this having much effect on our willingness to give aid to Omran’s equally affected – but unknown – fellow citizens.

Much of Bloom’s argument is based on utilitarian principles where the effective allocation of resources trumps the warm glow of a more singular and intimate concern. There are many good arguments against utilitarianism, but the book for me raised a different question. There has been much research into the seeming capacity of small children to respond empathetically, but what children appear to feel is not so much empathy, when they perceive someone in distress, as sympathy. Typically, children will pat, touch, hug or offer a toy to another child or adult in distress but only rarely in this situation show signs of anguish themselves. This brings me to my own particular beef, which is to mistrust the validity of the whole concept of empathy. How can we really claim to “know” what another truly feels? And what was wrong with the perfectly serviceable word “sympathy”?

A sympathetic understanding is an imaginative attempt to sense another’s otherness without purporting to appropriate or own their existential uniqueness. The belief in a valid empathetic response suggests to me a form of wishful thinking that we are fundamentally knowable to one another – which we are not. Nor should we need to be. Our differences are to be respected and are what make us interesting. Bloom doesn’t go as far as this, but believes that rather than claiming emotional identification we should be cultivating our ability to stand back in order to provide a more rationally effective programme of care.

This is not a view shared by Peter Bazalgette, whose book The Empathy Instinct: How to Create a More Civil Society goes a long way to validate Bloom’s belief that there is a fundamental muddle about what empathy means. For if one were to substitute “compassion” or “sympathy” here for “empathy” there would be little to disagree with. Where Bazalgette does differ from Bloom is in perceiving the capacity to put oneself in another’s shoes as the sine qua non of morality.

I am staunchly with Bloom here: it is undoubtedly a valuable gift, but only provided it is fortified by a prior rational moral position and appropriately judged action. And there are many arguably moral actions that have nothing to do with empathy or even sympathy – paying one’s taxes, or picking up litter are not glamorous activities but they stem from a rational perception of what is for the general good.

As the outgoing head of the Arts Council, Bazalgette’s book is at its strongest on the role of empathy in the arts, if empathy is what is really at work. As a writer of fiction I would suggest that what I feel for my characters is not so much empathy as an imaginative conception, which includes a readiness to toss them to the lions if that is what the arc of their fate dictates.

Salley Vickers’s latest novel, Cousins, is published by Viking

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion