NASA has initiated a process that raises questions about the future of its Orion spacecraft. So far, this procedural effort has flown largely under the radar, because it came in the form of a subtle Request for Information (RFI) that nominally seeks to extend NASA’s contract to acquire future Orion vehicles after Exploration Mission-2, which likely will fly sometime between 2021 and 2023.

Nevertheless, three sources familiar with the RFI, who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity, told Ars there is more to the request than a simple extension for Orion’s primary contractor, Lockheed Martin. Perhaps most radically, the RFI may even open the way for a competitor, such as Boeing or SpaceX, to substitute its own upgraded capsule for Orion in the mid-2020s.

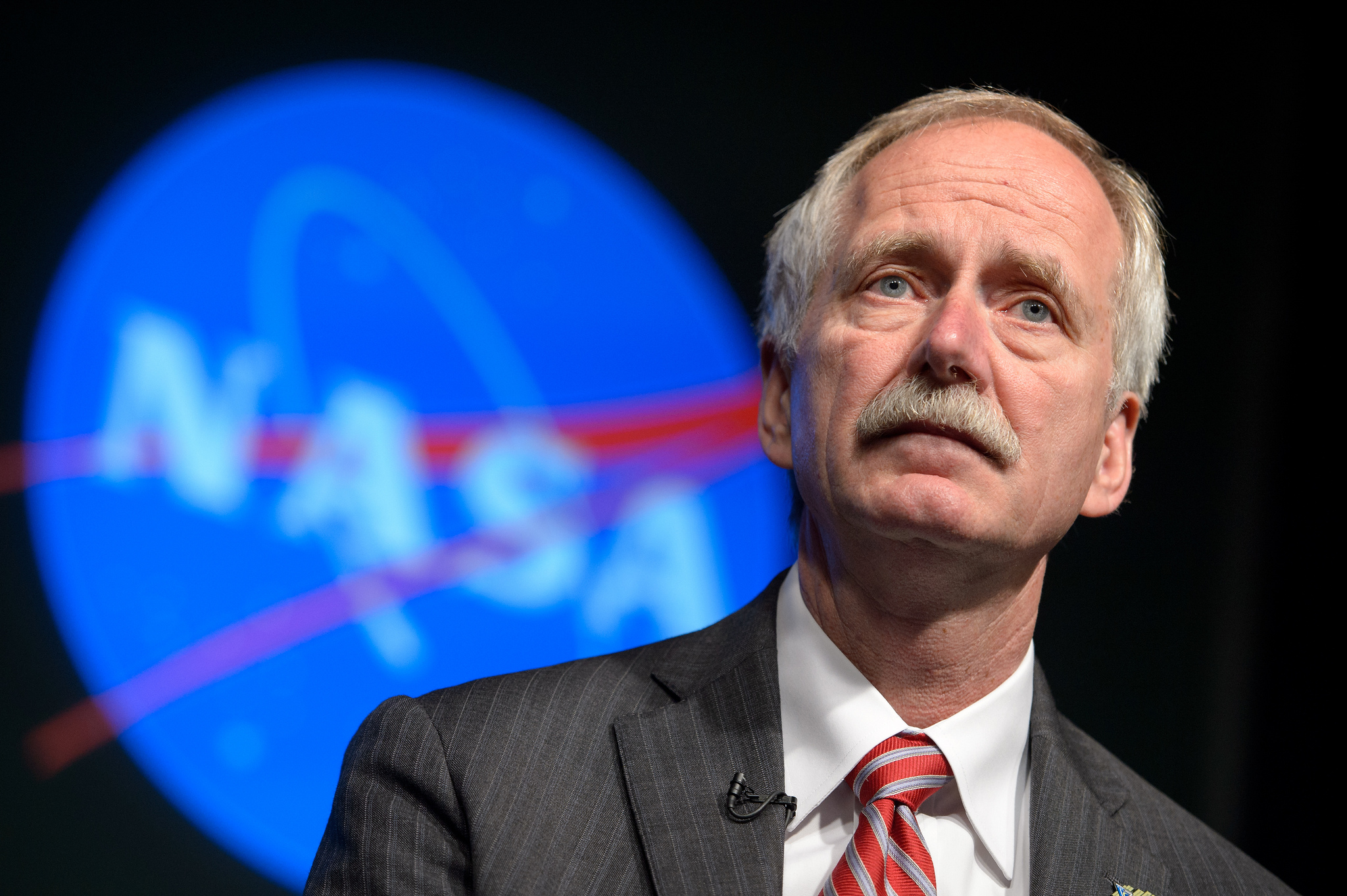

This RFI process, which originated in the Washington, DC-based office of the manager of NASA’s human spaceflight operations, Bill Gerstenmaier, appears to be an effort to keep the agency’s options open during a presidential transition. “This is NASA taking a breath and looking at alternatives,” one source told Ars. “Part of why they also did it is they are signaling to the next administration that they may be willing to look at alternatives.”

Lockheed concerns

In a heated competition a decade ago, Lockheed Martin won the initial contract to design and develop the deep-space Orion spacecraft, which was supposed to fly its first crewed mission in 2014. While the contractor has had to manage several significant change requests, there is nonetheless growing frustration with Lockheed inside NASA. The agency has spent nearly $10 billion so far on Orion, and although there was an uncrewed test flight in 2014, the first human mission won’t come for at least five more years.

The new RFI states that Lockheed will continue with development of Orion through a second uncrewed flight set for late 2018 and Exploration Mission-2, the first crewed mission, as early as 2021. However, once this “base vehicle” configuration is established, the RFI signals NASA’s intent to find a less expensive path forward. “This RFI serves as an examination of the market, which is an initial step in pursuing any of the available acquisition strategies, including the exercising of existing options,” the document states.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...