Racism and the Execution Chamber

The national death-row population is roughly 42 percent black—nearly three times the proportion in the general population.

After a seven-week freeze following Clayton Lockett's botched execution in Oklahoma, three states executed three death-row inmates in less than 24 hours last week. Georgia, Missouri, and Florida had tangled with defense lawyers for months over the secrecy surrounding their lethal-injection cocktails and where they were obtained, a key issue in Lockett's death. Florida also addressed concerns about its inmate's mental capacity; his lawyers claimed he had an IQ of 78. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected all appeals, however, and the three inmates—Marcus Wellons, John Winfield, and John Henry, respectively—were successively executed without apparent mishap.

In addition to their fates, Wellons, Winfield, and Henry have something else in common: They are among the disproportionate number of black Americans to have been executed since the Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976.

In the three states where they were executed, blacks constitute a disproportionate share of the death-row population relative to the state population. In Oklahoma and Missouri, black Americans are overrepresented on death row by nearly a factor of four.

These states aren't isolated examples. The national death-row population is roughly 42 percent black, while the U.S. population overall is only 13.6 percent black, according to the latest census. (The national prison population overall is roughly 39 percent black, according to the latest Bureau of Justice Statistics data.) Some individual states are worse. In Louisiana, the most carceral state in the Union, blacks are roughly one-third of the population but more than two-thirds of the state's death-row inmates.

We've long known that the death penalty disproportionally kills people of color. David Baldus, a University of Iowa law professor, and his colleagues studied more than 2,000 homicides in Georgia in the 1970s and 1980s for evidence of bias. Their landmark research, known popularly as the Baldus study, found vast racial disparities in Georgia's capital-punishment system.

A black inmate named Warren McCleskey, who had received a death sentence for murdering a white Atlanta police officer, challenged it before the Supreme Court in 1987 using the Baldus study, arguing that Georgia's racially discriminatory system violated his Eighth and Fourteenth Amendment rights. Justice William Brennan, who opposed the death penalty in all circumstances, explained in his dissent why the statistical evidence mattered:

At some point in this case, Warren McCleskey doubtless asked his lawyer whether a jury was likely to sentence him to die. A candid reply to this question would have been disturbing. First, counsel would have to tell McCleskey that few of the details of the crime or of McCleskey's past criminal conduct were more important than the fact that his victim was white.

Furthermore, counsel would feel bound to tell McCleskey that defendants charged with killing white victims in Georgia are 4.3 times as likely to be sentenced to death as defendants charged with killing blacks. In addition, frankness would compel the disclosure that it was more likely than not that the race of McCleskey's victim would determine whether he received a death sentence: 6 of every 11 defendants convicted of killing a white person would not have received the death penalty if their victims had been black, while, among defendants with aggravating and mitigating factors comparable to McCleskey's, 20 of every 34 would not have been sentenced to die if their victims had been black.

Finally, the assessment would not be complete without the information that cases involving black defendants and white victims are more likely to result in a death sentence than cases featuring any other racial combination of defendant and victim. The story could be told in a variety of ways, but McCleskey could not fail to grasp its essential narrative line: there was a significant chance that race would play a prominent role in determining if he lived or died.

Five justices disagreed with this assessment. The majority decision in McCleskey v. Kemp ruled that aggregate empirical evidence of racial discrimination could not invalidate an individual defendant's death sentence. "At most, the Baldus study indicates a discrepancy that appears to correlate with race," Justice Louis Powell wrote, "but this discrepancy does not constitute a major systemic defect."

Unchecked by the judiciary, the death penalty's racial discrepancy survived and thrived. Eleven years after McCleskey, Baldus studied 667 homicides in Philadelphia between 1983 and 1993 and found that black defendants there were nearly four times likelier than white defendants to receive a death sentence for the same crimes. Racial disparities in crime rates aren't a factor in this because homicide, the predominant capital offense, is an overwhelmingly intra-racial crime. Federal statistics show that 84 percent of white victims and 93 percent of black victims between 1980 and 2008 were murdered by someone of the same race. But death-row statistics don't reflect those rates: Although roughly half of all U.S. homicide victims are black, more than three-quarters of victims of death-row defendants executed since 1976 were white.

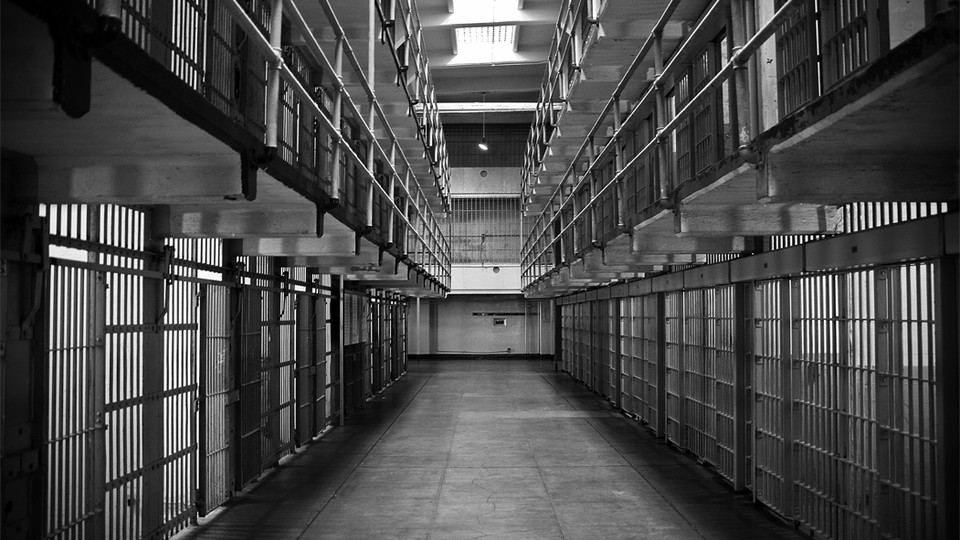

The McCleskey precedent also radiated throughout the criminal-justice system, from jury-pool demographics to departmental arrest rates and beyond, where the threshold to prove impermissible racial discrimination had been placed almost impossibly high. "African-Americans are stopped, ticketed, searched, and/or arrested by the police at far higher rates than whites," according to the NAACP. "Relative to their rates of arrest and participation in crime, African-Americans are represented within U.S. jails and prisons at unreasonably high rates."

"Within a decade of McCleskey, the number of minority citizens in prison exceeded the total number of persons incarcerated in the U.S. in the year preceding the decision," the NAACP concluded. By all but nullifying legal claims of racial bias in the capital-punishment system, the case steadily evolved into a cornerstone of mass incarceration.

Powell's biographer later asked him if he would change any vote he had cast during his tenure on the Court. In those 15 years, he had joined the majority in controversial cases ranging from Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion nationwide, to Bowers v. Hardwick, which upheld sodomy laws. "Yes," Powell replied. "McCleskey v. Kemp."

But other justices also recognized the flaws it embedded in the death penalty. In an impassioned and lengthy dissent in an otherwise-unremarkable death penalty petition's denial in 1994, Justice Harry Blackmun cited McCleskey as evidence that American capital punishment was morally and constitutionally indefensible:

Having virtually conceded that both fairness and rationality cannot be achieved in the administration of the death penalty, see McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279, 313, n. 37 (1987), the Court has chosen to deregulate the entire enterprise, replacing, it would seem, substantive constitutional requirements with mere aesthetics, and abdicating its statutorily and constitutionally imposed duty to provide meaningful judicial oversight to the administration of death by the States.

From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death.

[...]

The Baldus study further demonstrated that blacks who kill whites are sentenced to death "at nearly 22 times the rate of blacks who kill blacks, and more than 7 times the rate of whites who kill blacks."

Despite this staggering evidence of racial prejudice infecting Georgia's capital sentencing scheme, the majority turned its back on McCleskey's claims ...

Justice Antonin Scalia, who concurred with the majority in McCluskey, openly mocked what he saw as a "false, untextual, and unhistorical" legal argument from Blackmun. The New York Times noted Blackmun's unusual move in a lengthy article the following day:

Justice Blackmun's remarkable 7,000-word statement was aimed toward a future in which, he said, the Court would realize that the effort to administer the death penalty fairly and consistently was "doomed to failure."

"I may not live to see that day," he said, "but I have faith that eventually it will arrive."

Blackmun died in 1999. That same year, 20 states executed 98 defendants—the most since the death penalty had been reintroduced in 1976. One-third of them were black. The "machinery of death" whirrs on.