Trump's Favorite Voter-Fraud Activist Hedges His Claims

His work prompted the president's call to investigate the election—but now, he warns it’s too early to draw firm conclusions.

Did 3 million people vote illegally in the 2016 election? There’s no evidence that’s true, but President Trump certainly believes so, making news his first week in the White House by ordering an investigation into that allegation. Even if only partly substantiated, it would probably be the single largest instance of voter fraud in American history.

The source for Trump’s convictions seems to be a Twitter account run by Texan businessman and former public official Gregg Phillips, the founder of VoteStand, a mobile app designed to allow users to report incidents of voter fraud. Using data from conservative nonprofit True the Vote, Phillips claimed that he identified millions of illegal votes. Those claims went viral when published, were amplified by the conspiracy-theory website InfoWars, and ultimately reached the president himself. But those data have not yet been released, and questions about the credibility of their purveyor and his methods and claims abound. Even Phillips himself is now backing off the original 3 million number that sparked the president’s demand for an investigation, explaining that he needs more time before he’s willing to provide final numbers or release his raw data.

“Over a hundred million people voted. Impacting a presidential election is probably less likely than impacting anything down-ballot,” Phillips said. “I’m not gonna be goaded into going faster than I want to. I’m not a government official, I don’t have protections, and if I accuse somebody of voter fraud, we have to be sure that what we’re saying is right. While I believe I’m right, it’s in my best interest and everybody else’s best interest to make sure this is right.”

Phillips expressed some reservations about using his own methods as ironclad evidence of voter fraud, or as evidence that fraud affected the 2016 election. “Our interest in not in uncovering anything that might somehow change any past election, because once those votes are certified, they’re certified and that’s over,” Phillips said. “The work that we’re doing could create a foundation for looking at elections moving forward.”

The president, however, is still vowing to press ahead with a full investigation.

Until his bombshell tweet, Phillips maintained a relatively low profile. The Texan often discussed conspiracy theories about the Obama administration on Twitter, but the main target of his ire appeared to be any laws that could make it even moderately easier to vote. He criticized Obamacare not from the standard Republican context of health costs or government control, but because its expansion of instant Medicaid and welfare-eligibility verification might make it easier to register to vote, and harder to verify the identity of voters.

But Gregg Phillips isn’t just a Tea Party Twitter hero suddenly rising on the strength of a presidential cosign; rather, he’s a longtime Republican operative who has chased the specter of voter fraud for three decades. “Our first voter project I did when I worked for the GOP in Alabama back in the 1980s,” Phillips told me. “I’ve been involved off and on since then, and I’ve always said we need to ensure integrity in our systems.”

During Phillips’s decades of work in the area, no conclusive evidence of widespread voter fraud has been found, despite numerous investigations. A 2014 investigation from researchers at Loyola Law School found 31 instances of voter impersonation out of a billion total votes cast in 15 years, and noted that some of those could be technical errors, and not fraud.

Even investigations by Republicans have come up short in proving that voter fraud is a regular occurrence. The Justice Department under President George W. Bush “turned up virtually no evidence of any organized effort to skew federal elections,” according to The New York Times, and found that the few convictions for fraud were often simply the result of people making mistakes on voter forms. A similar investigation in Iowa under Republican officials also found scant evidence.

After beginning his political career chasing the idea of voter fraud in Alabama, Phillips became something of a regional player. He moved to the neighboring state of Mississippi in 1991 to run the fundraising operation of gubernatorial candidate Kirk Fordice. Fordice would go on to become the first Republican governor of Mississippi since the establishment of Jim Crow in the state. Fordice ran on a platform one contemporary journalist compared to that of fellow southerner and KKK leader David Duke, marked by his fiery rhetoric against affirmative action and welfare.

Phillips’s political career blossomed with the help of Fordice, who nominated the then-33-year-old to lead the Mississippi Department of Human Services in 1993. His tenure was brief and dogged by criticism from Democrats. According to The Clarion-Ledger, after he resigned in 1995, the Mississippi Performance Evaluation and Expenditure Review (PEER)—with the approval of some Republican state legislators—launched a probe into his decision to go work for Centec Learning, a contractor to which he had awarded an $878,000 deal while leading the Mississippi Department of Human Services.

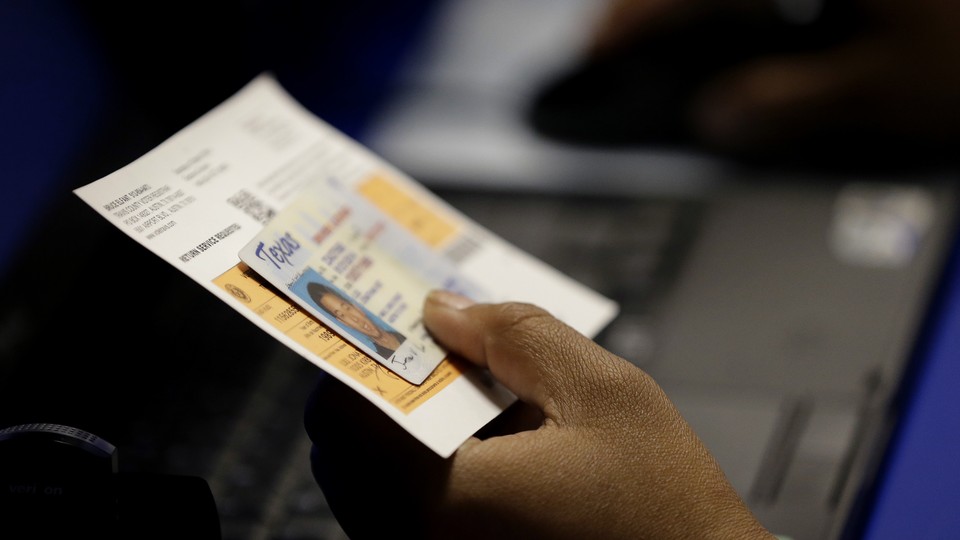

Phillips still had some cards left to play in Mississippi, however, and in May of 1995 he became the executive director of the state GOP, where he would serve until 1996. During his tenure, the Mississippi GOP aggressively pursued the specter of voter fraud in Mississippi’s “black belt” while supporting Fordice’s bid for reelection. Just a week before the 1995 election, the Greenwood Commonwealth and the Clarion-Ledger reported state GOP chairman Billy Powell sent letters to county commissioners asking them to instruct polling-site managers to check voter IDs before allowing people to vote, saying commissioners could be imprisoned for three months for allowing a person to vote without honestly considering his qualifications.

Mississippi did not have a voter-ID law at the time, and could not make changes to its voting practices without Justice Department oversight under the Voting Rights Act. Commissioners in majority-black Hinds County successfully sued for a restraining order against the party, and Justice Department observers came to the oversee the elections and ensure no black voter was disenfranchised.

Phillips’s stint atop the Mississippi state GOP and its attempts at voter suppression was also brief, and he worked in the private sector until 2003, when he was appointed the executive deputy commissioner for the Texas Health and Human Services Commission. Accusations of ethics violations again hounded his tenure, and a 2005 Houston Chronicle exposé claimed that his $1 billion privatization plan for the department might have benefited numerous associates and his own businesses that were granted contracts and deals. Again Phillips left the public sector for the private sector under a cloud of suspicion.

In our conversation, Phillips characterized recent scrutiny over the decades-old allegations as “nonsense,” and said it consists of personal attacks that are not germane to a discussion around the importance of his voter data.

Although he hasn’t held office since, Phillips has remained deeply involved with conservative organizing and fundraising. In 2011 he became the managing director and a principal for the Winning Our Future Super PAC, a $24 million operation started by former Newt Gingrich aides that supported his 2012 presidential bid.

Around this time, Phillips also became involved in the growing Tea Party movement. The first reports of his affiliation with fellow Texan and Tea Party operative Catherine Engelbrecht come from 2014, when the Voters Trust, a nonprofit run by Phillips, issued a $1 million “bounty” to anyone with information that could implicate the IRS in the targeting scandal involving Engelbrecht’s True the Vote, a national political nonprofit focused on voter fraud. (The IRS had targeted certain applicants for nonprofit status for increased scrutiny, based on keywords in their names.) Phillips says that he doesn’t recall how he met Engelbrecht, but their association became crucial to the allegations of widespread voter fraud that have rocked the first week of Trump’s presidency.

True the Vote has been a major player in Tea Party efforts to promote a more restrictive approach to voting rights. An offshoot of the King Street Patriots—a Tea Party group also led by Engelbrecht—True the Vote has long blurred the line between partisan advocacy and public-interest activism. It started its work in Texas in 2010, and began working in the Wisconsin elections in 2011, launching an initiative to send poll-watchers into neighborhoods of color, as well as an ill-fated attempt to invalidate thousands of names on a petition to recall Republican Governor Scott Walker.

Since then, True the Vote has expanded its focus to the national level, despite congressional probes into claims that it engaged in what amounted to voter suppression. It has supported strict voter-ID laws and promoted poll-watching across the country. Its quest for nonprofit status became a central piece of the IRS targeting scandal, but a Texas judge ultimately ruled that it functioned more as a political action committee controlled by Republicans than a true independent nonprofit.

Phillips is the public face of the claims of massive vote fraud in the 2016 election, but True the Vote’s vast network of volunteers and data that it says it has collected on elections form the bedrock on which Phillips’s claims rest. The webpage for the VoteStand app notes that it is “© 2016 True the Vote,” and its entry for “Team” consists of a capsule description of True the Vote.

“Catherine Engelbrecht and the True the Vote folks put the research database together and allow outside people to come in and analyze the data,” Phillips says. “The data comes from public sources. We’ve been gathering the data since 2009, and we use volunteers to analyze it, with a proprietary algorithm.” Based on that analysis and those data, those volunteers found several records of voters who had used a federal voter-registration form that they deemed ineligible, he says. “If it’s not 3 million, then pick a number,” Phillips says. “Some of those came from that federal form, wouldn’t it be in everybody’s interest to verify that information?”

Phillips walked me through his theory of how fraud from ineligible voters allegedly works. “If someone comes in and registers to vote using the federal registration form or the federal system, it’ll ask you a few questions and there’s a checkbox at the top that asks you if you’re a citizen,” he told me. “There are elements in the form below that like name, date of birth, that kind of thing. The problem in many people’s view is that that data is never verified. It’s all based on self-attestation.”

According to Myrna Pérez, the deputy director of the liberal-leaning Brennan Center’s Democracy Program, many states use electronic registrations, and states that use paper registrations already do verify them, contra Phillips’s claims.

“All first-time registered voters that do not apply in person need to be checked according to two numbers that a voter has an option of providing: either a Social Security number, or they provide a DMV number,” Pérez says. “There's a very specific process for people who have neither, but the vast majority of Americans will be providing one of those numbers. And under law, elections officials run those numbers to make sure that they can in fact find the person’s identity.”

According to Pérez, the main flaw in the voter registration and verification process is not that it is too lax, but that it tends to reject legitimate registrations. “We know that they do this because sometimes they’re overly rigid about how they match people up,” Pérez says. “We’ve actually sued a couple states for being too rigid in their verification process.”Given that the Social Security Administration and state DMVs already rely on complex databases of private information for verification, Pérez did not think it likely that third-party verification attempts could be more rigorous.

The problem with previous third-party efforts to verify—and challenge—public voter information is that they often use methodologies that have been quickly debunked. For example, during True the Vote’s campaign against the recall in Wisconsin, the state Accountability Board called their process “at best flawed,” and noted that it marked people as ineligible for reasons like including middle initials on petitions instead of their full middle names. And in a 2010 challenge by True the Vote in Houston, opponents charged that the group made several errors in its challenges.

Phillips’s response to an investigation into his own voting history provides perhaps the clearest example of the difference between his earlier claims of rampant voter fraud by “illegals” and the less-explosive claims he made in our conversation. After the Associated Press reported on Monday that Phillips himself is registered to vote in three states, he focused on the efficiency of the voting system itself. “That is not fraud—that is a broken system,” Phillips told the AP. Notably, the AP report states that Phillips was surprised by the revelation of his multiple registrations, despite claiming access to a superior voter-verification methodology and database.

Phillips would not share his methodology with me, though as he noted in an interview with CNN’s Chris Cuomo, he does plan on releasing public data. He says that his intent is to use the data to improve the integrity of elections moving forward. “In the end, it’s not going to be me or you or Chris Cuomo or anybody else who decides this,” Phillips told me. “The political leadership in this country deserves the opportunity to be able to look at the raw data and make their own conclusions, and fix it. Stop worrying about what happened in 2012 or 2016. That’s over. But we have to worry about 2018 and 2020.”

One question that Cuomo posed to Phillips seems particularly pressing: How could he make verified claims of 3 million ineligible voters, as he did on November 13, if he was still in the process of verifying his work? In our conversation, Phillips did not commit to a hard number, and expressed concern that his claims and methodologies might be seized upon and used for more nefarious reasons and motives. “We’re not in this to create a list of millions of people that we think ought to be deported,” he said pointedly. And he promised, again, to make his work public. “America deserves the raw data to check my methodology.”

Phillips seemed surprised by firestorm his claims created, and by the ensuing personal attacks and scrutiny of his past. And after all, how could he have expected that a sitting president of the United States who had just won an election would order an investigation into his own victory based on unverified analyses of unreleased data?

But the president already seems intent on moving forward with investigations. The claims are unverified, but perhaps the damage has already been done.