We know that the majority of Scotland backed staying in the EU – so with Brexit looming, why are polls not showing a resultant shift in support towards Scottish independence from the UK? It is clear that Nicola Sturgeon is trying to convince unionist remain voters to switch their allegiance, but YouGov has found that the first minister’s strategy is being offset by leave voters who backed Scottish independence now wanting to remain a part of the UK.

In the immediate aftermath of Britain’s vote to leave, much attention focused on Scotland and the potential breakup of a much older union. Sturgeon announced that a second referendum on Scottish independence was “highly likely” and there was an expectation among many that polls would begin to show a shift towards independence.

However, so far as our polling has shown, if there was another vote the result would be much the same as it was in 2014. Between August and December last year we polled over 3,000 Scottish adults and found yes to Scottish independence on 46% and no on 54% – just a fraction different from the result two years earlier.

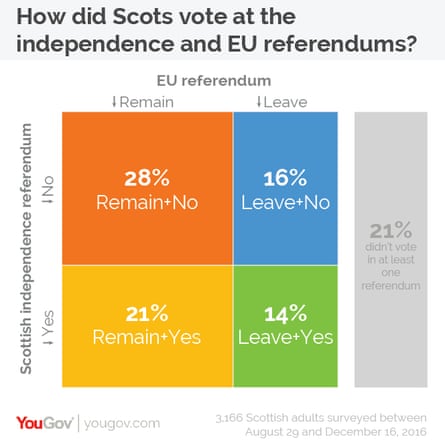

But this headline number conceals quite a lot of voter movement that has happened in a short space of time. Because of the large sample size, we can split the electorate up into four main segments based on how they voted in the Scottish independence referendum and the EU vote on 23 June 2016.

The largest segment, making up around 28% of Scottish voters, is those that voted no to independence in 2014 and then voted to remain in the EU in 2016. This is the key group that Nicola Sturgeon is hoping will tip a second referendum in her favour.

In the vote last June, Scotland voted to remain in the EU by 62% to 38%. The SNP’s strategy in the past six months has been to use the Brexit referendum result to illustrate that Scotland’s political will is being thwarted as part of the United Kingdom.

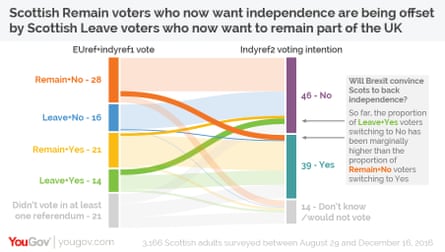

After this week’s supreme court ruling, Sturgeon said: “Is Scotland content for our future to be dictated by an increasingly rightwing Westminster government with just one MP here, or is it better that we take our future into our own hands?” However, so far, this argument has delivered only modest returns, with 12% of no/remain voters switching their vote towards independence.

So why has this small but notable shift not moved the headline numbers? The movement among this group has been offset by a much larger swing among those who voted yes to independence in 2014 but then voted to leave the EU last year. Despite only making up 14% of Scottish voters, 43% of these leave/yes voters have since abandoned their pro-independence position, with 28% now saying they would vote to stay in the union.

The other two groups, remain/yes and leave/no, together make up approximately 37% of Scottish voters and have remained reasonably consistent in their positions on independence in the aftermath of the Brexit vote.

This shows the difficult position that Sturgeon is in. To win a second time around, the independence campaign needs to win over more remain voters that voted to stay in Britain last time, without alienating the leave voters already in their camp.

The SNP may successfully find a message that allows it to do this, and there haven’t yet been any polls released in the aftermath of this week’s article 50 ruling. But so far the polling has shown this aggressive anti-Brexit positioning has lost as many voters as it has gained, and, were a second referendum held, the final result wouldn’t be much different. For a party with support divided between leave and remain, there’s going to be a difficult balancing act to be performed in the coming years.