Stavanger, Norway

The glassy waters barely disturbed the Sanssouci Star, a 174-foot yacht on which William Doll was hanging out one evening last August, anchored at a distance from the voluble quayside bars and restaurants of Stavanger.

On board was a gathering of Doll’s “private society,” a club whose primary condition of membership is at least a billion dollars in wealth. He and around a dozen members and guests, lolling around a long, candle-lit table, and dining on baked turbot served by a chef flown in from Copenhagen, were discussing a big new play in advanced batteries.

Shares were available for $100 million each, in case anyone was interested. That got the group chatting admiringly of Tesla Motors, the electric car company, which led to smaller huddles debating cold fusion, artificial intelligence, autonomous driving and billion-dollar startups. As an evening, it seemed flawless, an intimate mingling of science, technology and substantial fortunes, including all of the fine touches “to reflect their stratosphere,” just as his clients prefer, Doll later said. In his time in Stavanger, members even closed a business deal that, with his cut, covered his expenses “four times over.”

Around eleven, Doll called it a night—in just a few hours, he had to weigh anchor and sail north for a member’s castle. His dinner companions dispersed to their cabins, or hotels onshore.

Mr. 1%

I had been following Doll for much of last year with interest in his expertise—”the 1%,” the ultra-wealthy strata of American and global society that was central to the 2016 US presidential campaign and politics beyond its shores.

Vermont senator Bernie Sanders, the losing Democratic opponent of Hillary Clinton, predicated his entire campaign on the common man’s mortal struggle with the 1%. So did Donald Trump, who vowed to “drain the swamp,” and vanquish the diabolical “global financial powers.” Their combined salvos were instrumental in transforming the 1% from a flashy social phenomenon splashed across the covers of glossy magazines to a foil in an anger-driven campaign indicative of something very wrong with America.

Which is about where the issue sat—until Nov. 8, and Trump’s upset of Clinton, an election result that seemed to turn in large part on the stark divide between America’s rich and cocooned elite, and everyone else. Trump promised to stick it to the man (and at least one woman), and restore dignity to tried-and-true Americans. He himself was surprised when millions of ordinarily civil adults overlooked their bedrock values and put him in the White House.

A little over five months since those placid days aboard the Sanssouci Star, and 11 weeks after the election, Doll remains unsettled by the outcome, in particular the righteous ire behind it—over what can fairly be observed as a personal attack. If you care to be blunt, Trump’s election was, by extension, validation of a war against his club and its members—internationalists who scoff at borders and nationalities, and see only deals to be done wherever they may be. When Trump railed against ”radical globalization and the disenfranchisement of working people,” he was assaulting the 1%. “You could say these people are at fault for globalization—they are the 1%,” Doll told me.

A long, wiry man with a gravely voice and a penchant for hugging his clients, often while also capturing the moment with a selfie, Doll calls his club Syneidesis, which in ancient Greek means conscience. He started it four years ago, and is now wrestling with what comes next.

For starters, there is the question whether Trump’s accusations are legitimate. Is globalization truly to blame for the ills that he decried during the election? Doll doesn’t think so, even if saying so looks self-serving. The economic system is imperfect to be sure. The election dramatized what had been obscured, which is that large numbers of Americans have been excluded from the fruits of more open trade and borders. But Doll still sees something principled about the free movement of products, ideas and capital, with the reward of wealth going to the equity owners of enterprise. His members are not morally depraved for fighting climate change, for example, as Trump has seemed to suggest.

That has led Doll to a personal decision: As of now, Syneidesis (pronounced sin-EYE’-deh-siss) has been solely a rich-person’s preserve. But what if Doll explicitly identifies it as something more—as a vehicle for thwarting the dismantlement of the fabric of global economics and politics? Syneidesis can be a club for “conscientious investors,” Doll said, billionaires who not only seek company with other billionaires and to make more money—as his members currently do—but also to save the now-vilified construct known only by its abstract names, globalization and the “liberal world order.” “I can’t just stay on the sidelines,” Doll said. “We can be an investor group geared toward spreading this right kind of capitalism and globalization.”

Before he was catering to the ultra-wealthy, Doll, at the time wearing long hair and a long beard, edited documentaries. Since that did not pay the bills, he found a job organizing industry conventions, which is what he was doing when an acquaintance floated the idea of holding small, Davos-style art, geopolitics and business gatherings for well-to-do but somewhat isolated friends. Doll, who speaks German and Russian and is married to a Russian woman, possessed the personal raw material to mix with global plutocrats. Syneidesis was born.

Today it has a dozen core members in Europe, the Middle East and North America, each paying a $30,000 to $50,000-a-year fee, plus a small cut for deals closed through a Syneidesis relationship.

Technically speaking, the bar for joining Syneidesis is steep—$1 billion or more in assets, including $100 million in liquid cash. There is a larger pool of such individuals than one might think if those are your bylaws—as of January 2016, Forbes counted 1,810 billionaires on the planet. And that is a selling point, because for such people, the brotherhood of one’s own kind is the essential elixir. Syneidesis’ other main attraction is a promised exposure to business deals available nowhere else, exclusive opportunities with a better than average chance of a bonanza. That is the reason for the large cash requirement: To attract entrepreneurs willing to grant Syneidesis first crack, Doll’s members must be prepared to play big, and to lose or win with the same geniality.

Yet Doll’s rules are calculatingly flexible. One of his tightest members, for instance, is Carl Page, an idiosyncratic Silicon Valley technologist with a wicked sense of humor, and his charming and intense environmentalist wife, Barbara. Although he earned tens of millions of dollars creating and selling tech companies in the 1990s, Page is worth less than a billion dollars. But his other cachet is that he is the older brother of Larry Page, the Google co-founder. At a Syneidesis dinner at Carl’s Palo Alto house one year, Chicago investment tycoon Steve Stevanovich was surprised when Larry Page showed up, and in a surprising way. “You imagine him arriving in a helicopter or a limo,” Stevanovich told me over lunch, “but you don’t think of Larry Page arriving on a bicycle.”

Then there is Peter Littlewood, the British-born director of Argonne, the Chicago-based US federal laboratory. Littlewood is also not a billionaire, nor in possession of big ready cash. But he is a priceless Syneidesis member, speaking with the easy, polished charm of a diplomat, and the quiet authority of a former director of England’s legendary Cavendish Laboratory and, before that, the theoretical physics department at Bell Labs. Most important, Littlewood is the doorkeeper to among the most valuable future Syneidesis investments—the inventions at Argonne, fundamental advances in nano-technology, big data, battery science and more. Syneidesis members see the potential for serious investment at Argonne.

As it happens, Doll has not been alone in pondering the substantial wealth that might be mobilized to create a sanctuary for globalization—to salvage the very ecosystem that has nurtured the biggest fortunes in history. Among those on a similar track is billionaire Bill Gates.

But the odds against them are exceptionally high, in part because they appear to be going up against not just Trump and the architects of Brexit, but a much stronger, fundamental force—the historical cycle.

We forgot the victims of globalization could vote

From the outset of 2016, the ultra-wealthy seemed to cast a shadow over the election. Whether or not they originally nettled, Sanders and Trump said they should—that ordinary people were rendered small by the gobbledy-gook spouting, super-rich, politically powerful masters of the universe, some working in investment banks, some in Washington, but all exercising undue influence over middle America. We needed to “take back our country” from “the elites.” “We will no longer surrender this country, or its people, to the false song of globalism,” Trump said last April.

Despite such prodding, most observers of the state of affairs assumed that the lanes were more or less static. Salaries had been stuck for decades, and wealth was more concentrated than ever. But the class juxtaposition was simply how it was; although no one knew how or when, somehow, sometime, the lifestyles of ordinary people would improve.

Meanwhile the middle and under classes would stand by while the normal course of public policy went on. The Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011 seemed to have fizzled. And the Tea Party seemed like so many insular rabble-rousers. Few suspected the French Revolution was still in the offing.

Then, all at once, the world—from Brazil to the Philippines, to Britain, Turkey and Poland—began to shun mainstream political experience and elect fringe figures, extremists of various sorts, and big, taunting personalities. Among the new politics, millennials across the democratic world began to speak of an openness to military dictatorship.

Some said we had reverted to the 1930s, perhaps the 1910s, or even earlier.

What did we miss?

That question has vexed historians, politicians, pundits, journalists, and a lot of other people—including Doll’s club members. So far, in terms of explaining the phenomenon of Trump’s victory, the expert consensus has cited a recipe of wealth inequality, a popular unease with migrants, a dash of lostness in society, and a sprinkling of bigotry and sexism. For one or more of these reasons, experts say, some 63 million Americans dispensed with their observed behavior over decades, and, in a determined pique of anti-establishment rage, elected the brusque real estate tycoon. They have ascribed the same combination to the June 2016 victory of Brexit. But are they right?

They are, in the way that a soup has many ingredients. But the nagging feeling is that the picture is incomplete—that we have all ingredients and only a thin gruel for our trouble. For starters, none of the purported reasons for the wave of uprisings is new—inequality, disorientation and a suspicion of outsiders have been with us for some time. Nor for that matter are ambitious, big-talking, kumbaya-promising, hate-bating populists anything special—they have been factors since Moses and probably before.

What the analyses are missing are time and context—the social physics: The stark possibility that the above ingredients contributed to the anti-establishment wave, but that their potency has been amplified by the turn of a historical cycle.

For decades, scholars have discerned patterns in the long arc of events. Big, sprawling history appears to move in cycles, at turns reinforcing and at others annihilating the existing way. Brexit and Trump make sense if you know that, over time, seemingly immutable norms and institutions have routinely proven to be in fact unfixed. Seemingly unassailable rulers, businesses, nations and whole civilizations have at once vanished, and so have the eras in which they thrived. What triggers the rise and fall of epochs—what drives the cycles—is probably unknowable, except for the complicity of humans themselves, with their unpredictable triumphs and blunders. But scholars have attempted to document the shape and character of the cycles.

Go back in US history: Ever since George Washington, government has swung between liberal and conservative. This is true for all 45 presidents, according to Yale professor Stephen Skowronek, a leading theorist on political cycles. Some scholars say the liberal-to-conservative-to-liberal epochs have happened at more or less predictable, 16-year intervals. Others say they have been longer, and have less resembled circular-shaped cycles than zigs, zags and spirals. Whatever the case, as an organizing principle, epochs impose order on an otherwise chaotic world. You can start to see human events much more clearly if you group them first.

So if the story of 2016 is one of a cycle turning—which seems to be the case—it’s understandable that scholars, journalists and other observers have been rushing to give the doomed epoch a name. Figuring out what precise cycle has ended has proved to be much harder than it seems it should be, but doing so is crucial if you care about what comes next—and especially if, like Doll, you need to know just what you may already be in battle against.

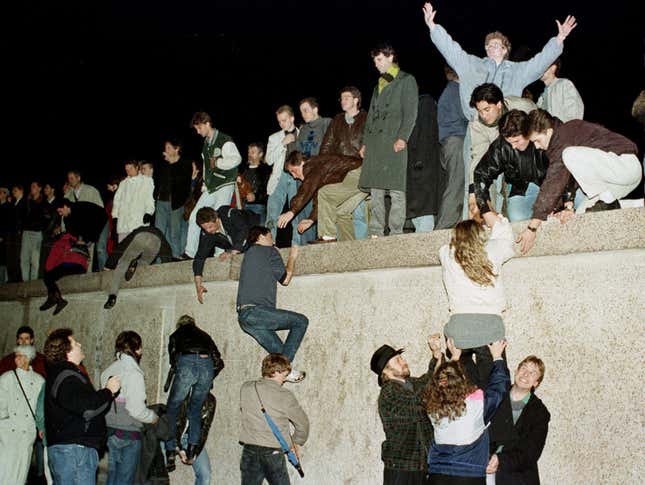

If what’s over is supreme American global power, for example, that means we are observing the end of the post-Soviet era, meaning a cycle lasting roughly from the end of 1991 through now; it suggests that we are entering a period shaped by dispersed global power. But if it’s the liberal world order that’s ending, that suggests an epoch beginning right after World War II, a roughly 70-year cycle, and the actual disintegration of the global system as we know it.

The answer depends on whom you ask. According to Columbia University professor Mark Lilla, we are watching the dying throes of the Sixties and the advent of identity politics. Walter Russell Mead says Americans have simply reverted to their Andrew Jacksonian roots, returning to the persnickety politics of 1820s nationalist self-reliance.

Francis Fukuyama, a Stanford professor, conceived the most famous cyclical descriptor for modern geopolitics, calling it “the end of history.” He thought a cycle ended with the Soviet collapse, and that another began—the demise of closed societies championed by Moscow, and the triumph of US-led free trade, more or less open borders, and democratic, honestly contested elections.

Today’s upheaval and president Vladimir Putin’s reassertion of Russian power say something different: that the Soviet collapse was a historic turn, but less definitive than Fukuyama had proposed. To grapple with the current zeitgeist, you have to go back further, he now says—to the late 1940s and 1950s and the Marshall Plan, US president Harry Truman’s blueprint to rebuild Europe and, with a host of financial and military institutions, resist the spread of Soviet communism into Europe.

It is the US-led world order, established during those eventful years, that is under siege. “The US was determined to buttress an internationalist elite after the war that would stand up to authoritarian pressures on the left and the right,” said Benn Steil, chief economist at the Council on Foreign Relations and the author of a forthcoming book on the Marshall Plan.

Even as he was writing his famous tract almost three decades ago, Fukuyama seemed to anticipate today’s events. People would tire of peace and prosperity, he said, and destroy it. “If men cannot struggle on behalf of a just cause because the just cause was victorious in an earlier generation,” he said, “then they will struggle against the just cause.”

“The real question should not have been why populism has emerged in 2016,” Fukuyama wrote after Trump’s election, “but why it took so long to become manifest.”

The leaders of this movement describe their rise in words reminiscent of physics. “We are experiencing the end of one world and the birth of another. We are experiencing the return of nation-states,” French politician Marine Le Pen said at a Jan. 21 gathering of far-right parties in the German city of Koblenz. The previous day, in his inauguration address, Trump himself drew an explicit line between his presidency and everything that went before it, calling it the result of “a historic movement, the likes of which the world has never seen before.”

How will the cycle play out? If Le Pen wins the French presidential elections this year and Angela Merkel is defeated in Germany, analysts foresee the demise of an experiment in defusing nationalism and uniting former wartime adversaries. Even if Le Pen loses, her adversary, François Fillon, is also in some ways in Trump’s mold, vowing to “break down the house,” and, like Le Pen, likely to cozy up to Putin. “The liberal world order’s days are numbered,” said Mathew Burrows, former counselor to the US National Intelligence Council, which synthesizes the work of the 17 intelligence agencies.

Behold the world of ‘authoritarianization’

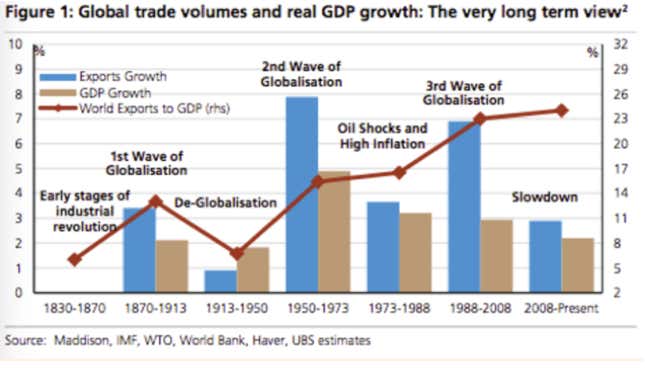

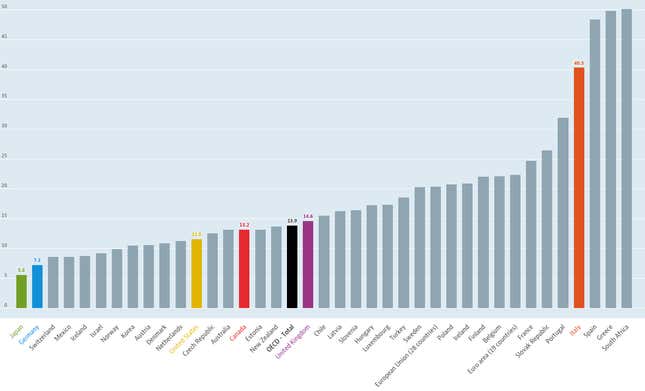

Some experts say the social physics are much less intimidating if you observe them through the lens of the Industrial Age. UBS, the Zurich-based bank, suggests that we are not witnessing a reprise of Rome circa 476, if that inflection point of superpower decline is what you fear. Instead, we are in the midst of the latest in two centuries of globalizations that have collapsed, one after another, only to revive when nations again seek advantage in cooperation (see chart below). If UBS is correct, a new liberal order will return in a few decades.

But a painless prognosis for cyclical turns is valid only if you ignore the possible misery of the experience. And the one we are on the cusp of—while unknowable in detail—has many people worried. In Foreign Affairs, Andrea Kendall-Taylor, a deputy on the US National Intelligence Council, and Erica Frantz, of Michigan State University, say we are moving into a new authoritarian period, a time when populists will use their public support to erode democracy and assert “personalist dictatorship.”

Our anti-establishment politicians are denying that is the case and calling those who suggest so worry warts, sore losers, and worse. But Kendall-Taylor and Frantz say that is what one should expect in a time such as now, when most people would not vote for an anti-democratic leader. To get there, they require a transition period that Kendall-Taylor and Frantz call “authoritarianization.” This is the act of conditioning a nation to embrace an authoritarian bent.

The standard method of authoritarianization goes like this: you appoint loyalists into the judiciary and security agencies, move on to defenestrate critics within your party, neutralize the media through accusation and delegitimization, and single out individuals for special scorn. So slowly are these steps taken, say Kendall-Taylor and Frantz, that it is “hard to discern when the break with democracy actually occurs.” That is one reason why “its insidiousness poses one of the most significant threats to democracy in the twenty-first century,” they say.

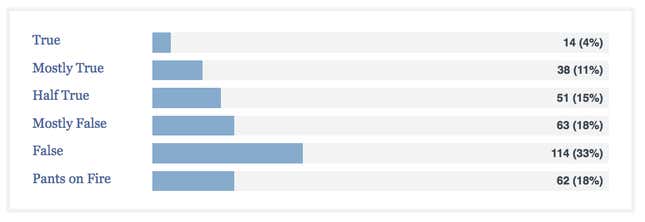

Since declaring his candidacy in June 2015, Trump has appeared to be taking pages out of the authoritarianization playbook. He has attacked 305 people and entities big and small, according to a running tally by The New York Times, often astonishingly infantile tirades that have nonetheless destroyed political rivals, brought others to heel, alarmed foreign powers, and plain annoyed a lot of people. He is now intimidating Washington power centers into accepting his one-man leadership—the intelligence agencies, the Federal Reserve, and Congress.

But Skowronek, the Yale professor, suggests that the anti-establishment wave is in for some shoals. Skowronek is best known for his theory of “political time,” his observation of a fixed pattern of cycles that has governed US politics since the revolution. Trump has thrown everyone off his game, but Skowronek argues that that needn’t have been the case if anyone paid attention, say, to the rise of Herbert Hoover and Jimmy Carter. In their respective eras, they, too, were outsider candidates who claimed unique traits to fix what ailed the country, and won long-shot elections.

Here is where Skowronek has some potentially bad news for Trump: So nightmarishly bad did both the Hoover and Carter presidencies unfold that they triggered opposing cyclical swings lasting generations—in the case of Hoover, FDR’s New Deal politics, and with Carter, Ronald Reagan’s sunny Republicanism. In this scenario, Trump will have a rough four years before being thrown out of office and being succeeded by a Democrat.

Skowronek is not alone in forecasting a difficult time for Trump. But mostly, a lot of people invested in the last cycle are having a hard time giving it up. In a blunt-spoken Nov. 9 note of congratulations to Trump, German leader Merkel made it plain that she remains loyal to the old ways, and that she expects him to respect them, too. “Germany and America are bound by common values—democracy, freedom, as well as respect for the rule of law and the dignity of each and every person, regardless of their origin, skin color, creed, gender, sexual orientation, or political views,” Merkel scolded. “It is based on these values that I wish to offer close cooperation, both with me personally and between our countries’ governments.”

But more recently, Merkel, who is running for re-election this year, has seemed to conclude that the cycle may be working against her. After Brexit and the shock from Trump, she is hardening her stance on migrants. The calculus appears to be that, even if she can’t beat the physics, she may prevail over the politics. Former French prime minister Fillon will have to do the same to beat Le Pen.

The West is not the only place vulnerable to the new social physics. Even after the tragedy in Syria, experts think the Arab Spring still has not run its course—the cycle is not played out. In a new report, the United Nations Development Fund is warning of an explosion of youth frustration over the lack of opportunity. The continued failure of Arab countries to deliver improved job prospects, the report said, “is leading young people to form negative perceptions of society and the future and providing a fertile ground for radical thinking and radical action among youth.”

* * *

If the pessimists are right—and it seems they are—Doll’s billionaires and others like them may be one of the few forces that the new populists may have trouble steamrolling over.

Not so fast

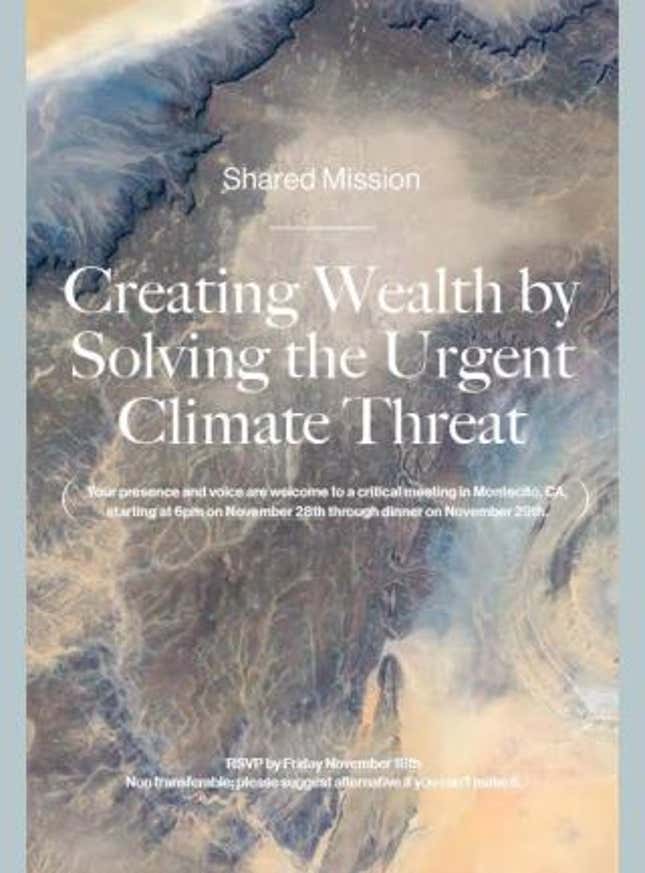

Three days after the election, Michael Smith, a high-end professional disc jockey in Santa Barbara, California, fired off an email to wealthy investor friends and climate activists. They needed to drop everything and meet post-haste. Whomever they had supported in the election, it was time to regroup now that the US had a president-elect who rejected climate science. Doll was among those who bought a plane ticket and flew to California.

Smith’s gathering of venture capitalists and advisers to rich clients convened on Nov. 28. Wesley Clark, the retired general, delivering the keynote address, said that climate change is a “threat multiplier” that roils the global order; as Smith hoped, Clark urged the crowd to act.

Noah Deich, another organizer of the meeting, said that the gathered group of investors were always inclined to support technologies that could staunch the worst outcomes of climate change—but only if they met their standard profit thresholds. They were happy to help to cut carbon emissions, as long as they made money doing so. But as of now, such technologies rarely did. So “trillions of dollars” remained “on the sidelines,” Deich said.

The election had made people more determined to find a financial structure that would attract that money, and thus take over where US support under Trump would vanish. Those trillions were again in play. “We saw an opportunity to convene voices that frankly we were not listening strong enough for before the election,” Smith told me.

Two weeks later, Bill Gates, also aiming to confront climate change, announced a $1 billion investment fund for clean energy. Alongside him was a phalanx of the world’s leading plutocrats, among them Alibaba’s Jack Ma and Mukesh Ambani, chairman of the Indian giant Reliance Industries. While unrelated to the anti-elite uprising, the Gates fund might as well have been—a vanguard of the 1%, defending a political outcome explicitly scorned by Trump.

In a way, such spending is not new—in 2007, the Rockefeller Foundation coined the term “impact investing” to describe making money while also doing good. The foundation established ratings systems that score investments by their social or environmental virtues. Today, investment banks say their clients have hundreds of billions of dollars in such accounts.

But Doll’s venture takes impact investing into a new dimension, explicitly aimed at preserving the political and economic system itself.

His decision point came on fast with Trump’s election. A day after, Doll was in Arkansas on business. By phone, he had been consoling his mother. “She is heartbroken,” he told me in an email. Doll himself didn’t seem to be faring much better. “Starting to rethink the role of an international coalition of prominent families,” he said.

Already, Doll was talking of “pivoting”—of somehow resisting the centrifugal forces pulling apart the post-war world. He spoke of telling his members, “You need to stand up and show the good you can do. Show you can invest in projects that produce good jobs.” “We need to show the fallacy that the elites are only in it for themselves,” he said.

In conversations over the subsequent weeks, Doll said Syneidesis’ multi-national families would reject the current mantra of distrust of experts, elites, science and institutions. They would invest together in “solid infrastructure and social projects. We will do economic diplomacy, in investments, to being keeping our countries’ interests aligned.”

Doll’s partner-in-arms was Raphael Auerbach, the CEO of a Zurich-based wealth management firm. I had met Auerbach aboard the yacht in Stavanger. A youthful-looking man with a soft beard and timbre, he controlled a considerable sum of money. And, when I rang him up after the election, Auerbach sounded a lot like Doll.

“Something has to be done,” he said. He feared that US government investment in science—hundreds of millions of dollars a year that many regard as the backbone of American technological and economic primacy—will falter under Trump, with his demonstrations of impatience with complex topics and rushes to judgment. “We are neither left nor right,” Auerbach said. “It has more to do with cutting through the bullshit of the politics. Focusing on science and the real stuff. But there is a huge fear of what is happening with Trump.”

In December, Doll and Auerbach, among a team, began to work on registering Syneidesis as a Swiss-based foundation, a legal format that will make the club more understandable to European investors. They are writing their own benchmarking system resembling the Rockefeller metrics for impact investing, but with scoring for globalization: Doll said that, for instance, on a scale from negative to plus 100, investments can be gauged for fairness to labor, capacity to strengthen strategic geopolitical relations, and their potential to sustain surrounding jobs and markets after a deal has run its course. “Even with a mine in Guinea, markets spring up around it. You want to engineer a deal so those markets don’t die,” Doll said. He said that all Syneidesis investments will be scored this way.

When added together, the picture was of a still-embryonic line in the sand, drawn by the world’s billionaires. They would fight Trump. “We are creating a global coalition of families—a UN of families that control the world, coming together for something bigger than their own personal gain, who are already doing this,” Doll said. “This group will be ready to stand up, to invest in ways that will safeguard democracy and democratic institutions, and support governments whose democracies are under threat.”

The plans sounded terrific on paper. But what about the cycles—are the billionaires ultimately in a battle against historic forces?

The forces are gaining potency

One of the most important theoretical forces of the Industrial Age and beyond was revealed by the Luddites, the early 19th century weavers who rose up against machines that were taking their jobs. Because all or many of the Luddites did find work despite the obsolescence of their manual skills, they became forever associated with numbskulls, in this case those who do not understand that new technologies arise and absorb displaced workers: A new machine negates demand for a certain category of workers, and they suffer a period of joblessness, but they then move on—sometimes to other cities and states—and find new occupations, often in previously non-existing businesses. Milton Friedman, among the leading purveyors of this line of thinking, famously said that human wants are infinite, and that demand for new products thus will keep us employed.

Yet, economists are now in a panic, along with politicians, professionals and workers of all types. They are worried about the new and expanding age of robots, and the possibility that they will wipe out whole classes of professions—lawyers, Wall Street brokers and analysts, accountants, journalists and more. Because of the scale of the impact of machine learning and artificial intelligence, this time, it is feared, Friedman will meet his Waterloo; the Luddites will be found to have been correct after all, and the ostensible law that Friedman explained will no longer apply. We do not know the degree to which the alarm is valid—if we are at the onset of an age of job-killing robotization, leaving us all in soup kitchens, and exacerbating our social and political chaos, or whether technological history will follow its usual course. But this is precisely what Doll’s globalization metrics are designed to gauge—how much an investment can be deliberately tailored to combat the inadvertent destruction of technological progress.

In an October note to clients, UBS said that if we are heading into a massive job crisis, it is not apparent yet in the statistics. But Brexit and the 2016 US election tell a different story: that technology and trade deals do not necessarily find jobs for all displaced workers, and that the result can be devastated stretches of cities and states with much lower wages, higher unemployment, and profound social pathologies. Beginning in 1980, the US manufacturing sector alone has lost 36% of its jobs, down to 12.2 million, according to the Brookings Institution.

A key barometer of future anti-establishment restiveness is the degree to which technology absorbs new workers coming onto the job market. Some 20% of youths across the EU are unemployed, a statistic that, country by country, reveals the strengths and limits of the populist wave: In a referendum on Dec. 4, voters in Italy, with about 40% youth joblessness, bucked the establishment by spurning prime minister Matteo Renzi, who had hoped to strengthen his hand and halt the country’s chaos; but Austria, with just a 10% youth jobless rate, rejected the far-right wing, which sought to veer away from the status quo.

Other factors obviously contributed to the opposing election outcomes, too. But the results reflect the instrumentality of youth unemployment as a proxy for underlying societal fragility.

Italy’s employment problems are the fault of inept government and flabby business—no one, it seems, can get their act together. But automation is to blame for most of the manufacturing job losses in the more competent parts of the developed world, according to numerous studies, along with the failure of youth to find employment. In the US, automation is responsible for 85% of all manufacturing jobs lost since 2000, the Center for Business and Economic Research at Ball State University says.

It is the same everywhere. “I don’t think globalization is the real issue. The real issue is automation and artificial intelligence,” Ted Goertzel, a professor at Rutgers University and co-author of Presidential Leadership in the Americas, told me.

If automation is the genuine, hidden source of the anger in rust belts everywhere, worse is on its way—far worse.

It is worth looking at the state of Michigan. The decade up to and including the Great Recession hit Michigan hardest of any state in the US. From 2000 to 2009, it lost 17% of its jobs—806,000 of them, more than a quarter, in the auto industry. And that excludes the latest tsunami to hit cars—electric mobility and autonomous functionality. According to the consensus, we are headed into an age of ubiquitous robot cars.

We may own a single car for convenience, but mainly, according to this line of thinking, people in cities and their suburbs will hail a robot car using an app, and be whisked away to work, their next meeting, shopping, the airport, home, wherever. There is reason to quibble, but let’s look at the outcome if the consensus is correct.

According to Barclays, this shift would wipe out 40% of US light car sales, reducing them from 17.5 million sales in 2015 to about 10 million in 2030. The number of cars on American roads will drop from 250 million to 100 million, according to the bank. As a result, the number of North American car assembly plants required by GM and Ford will fall from the current 30 to about 17. The US auto industry currently employs 7.2 million people including parts suppliers and dealerships. After the forecast autonomous revolution, the number will be far fewer, although neither carmaker would venture an estimate of how many.

The shift to electric cars, too, will cost jobs. VW says that by 2025, 25% of its new cars will be electric, and will require far fewer workers to manufacture—the German carmaker plans to cut a “five-digit number” of jobs. This is because electric drive trains require fewer parts than fuel-propelled technology. Multiply that across the industry, including US car assembly plants, and hundreds of thousands of jobs could be lost globally.

Then there are society’s professional drivers—4.6 million truck drivers in the US alone, and 234,000 taxi drivers, according to government and industry figures. As of the end of 2015, Uber also employed an estimated 1 million drivers around the world, ahead of its plans to get rid of them as fast as possible and operate mostly robot cars.

Meaning that, if the projections are accurate, millions of auto workers and drivers stand to lose their jobs to automation and electrification over the coming decade or two. “Certainly vehicle sales falling by 40% would be devastating to the Michigan economy, unless GM somehow monopolizes the market for self-driving cars,” said Chris Douglas, a professor at the University of Michigan.

When you consider similar vulnerability in the financial, legal, clerical and other analytical sectors, you grasp the scale of dissatisfaction ahead–almost certainly much greater than what produced Brexit and Trump.

Can the 1% preserve what’s best of globalization?

Recently, Doll posted a description of his plans on the internet, a call to action that he called the “Justice League of the G20.” One of his close business associates, a strong supporter of Trump’s, responded by calling Doll “unAmerican” and “borderline treasonous.” Doll had foreseen objections from some of his clients, but reckoned that, pragmatically speaking, even if some bailed, he might attract an even larger membership of other billionaires discomfited by the transformation of politics. “If I am shooting 1 out of 10, that’s fine,” Doll said.

But his friend Auerbach thinks that, even if Doll reaches that goal, it won’t be enough. They need more to create the necessary critical mass. They need bigger billionaires. “As long as you don’t have the chairman of Blackrock sitting there listening, I don’t think it will make a big dent,” Auerbach said. (On Dec. 2, Trump named Blackrock chairman Larry Fink to his informal Strategic and Policy Forum.)

Doll and his billionaires may save some of their pet causes, like clean energy technology. But there is a limit to their power, and one thing they cannot save is Western democracy. For democracy to work, an unconditional requirement is a hard-and-fast societal insistence on the truth: Facts have to matter, and those who demonstrate a light regard for them or outright lie must face scorn. This is because the opposite is how authoritarian systems survive—they rely on truth being fungible, relative and cheap, thus allowing them to claim one thing, do another, and, often, help themselves and their friends to a nation’s wealth.

Trump’s fast and loose attitude toward facts (see below), and the country’s own emotional embrace of often-intentionally conspiratorial, evil and utterly absurd claims about the world, demonstrate that self-governance is in serious trouble. It is the precise environment that authoritarian personalities traditionally seek—one in which they are cheered by a populace seeing security in an outsized personality. And it is just such circumstances that have led to many of the most tragic events of the last century.

Mind you, this puritan standard of truth is relatively new, at least for Americans. It arrived through Watergate and the Vietnam War, building on the more fundamental American legends of Washington and the cherry tree, and Honest Abe Lincoln: American leaders could not lie, and they had to stand up to power that did. This fanaticism about truthfulness is why the world more or less knows what went down in Iraq over the years. It is ultimately why Edward Snowden and Julian Assange are consequential people—because revelations about NSA spying, global diplomacy and hidden wealth are facts, and not someone’s fevered imagination. It is why it is unacceptable to recast falsehoods as “alternative facts,” as senior Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway did on Jan. 22, attempting to swat away inaccurate claims by the president and his chief spokesman. Or, as Conway was actually doing, to attempt to transform the norms of honest discourse to resemble a Nov. 30 assertion by Trump surrogate Scottie Nell Hughes—that “there’s no such thing, unfortunately, anymore as facts.”

And it also may be why we are entering a new historical cycle: Public indifference toward the truth and their institutional pillars has allowed skeptics to force a shift to a new way.

There is enough blame to go around, and no one should feel relaxed with the outcome—liberal politicians have failed with social programs for decades; so have conservatives, with cutting-at-all-costs anti-tax and anti-union policies that have robbed communities of decent infrastructure, sufficiently paid teachers, and well-paying, protected manufacturing jobs. More open trade has taken about a billion people out of poverty around the world; but it has not stopped—and may have accelerated—the riptide of technology that has torn through US states. Both ideological spectra have supported trade policies that have hewed close to theories while doing too little to pragmatically protect communities.

Yet what does any of that have to do with the rejection of science, the menacing of the vulnerable, and the vilification of minority ethnicities, all qualities of Trumpism? The champions of this evolving new order are too enamored with authoritarian methods, presuming that the iron fist—as demonstrated best by Russia’s Putin, so far the biggest beneficiary of the new historical cycle—will bring a better day.

Doll expects an “absolutely uphill battle” recruiting more billionaires to his idea. One need only observe the scenes of the last two months to grasp what he means, such as Trump Tower on Dec. 15, and a roomful of Silicon Valley billionaires, previously contemptuous of the real estate magnate, now making peace with him. Big tech companies need to figure out how to work with the new administration, and their CEOs showed the path that they will generally take with Trump, which is not Doll’s. It is generally the same on Wall Street, with the flow of finance industry billionaires into Trump’s cabinet.

What Doll hopes is that the anti-establishment fever will eventually break. Meanwhile, he and his billionaires will have played a role in reintroducing the fairness and sensibleness that lay at the core of the era that appears to have all but passed into the cycle of history.