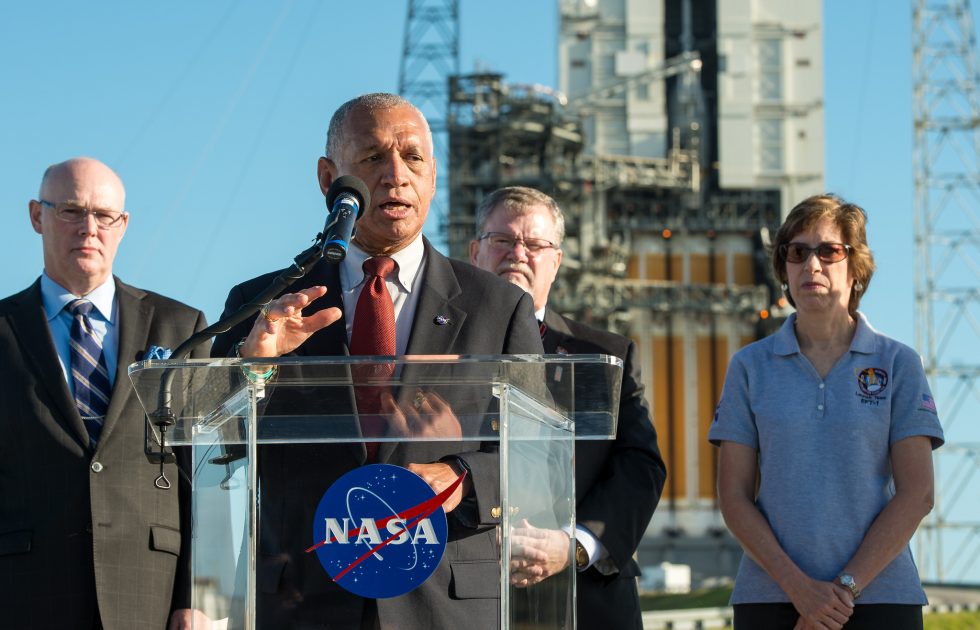

Charlie Bolden’s moment of triumph finally arrived on a warm December morning about 18 months ago. As he spoke of things to come, the Florida sunshine seemed to rejuvenate the decorated Marine and four-time astronaut. He’d survived five difficult years at NASA’s helm, taking knives from Congress, frustrating his former astronaut colleagues, and perhaps most painfully, watching helplessly as America became reliant on Russia for getting its own people into space.

But those difficulties were past. That morning at Kennedy Space Center, Bolden proudly said NASA was taking its first step on a “Journey to Mars.” As a buttress to these words, the mighty Delta IV rocket loomed behind Bolden with the shiny Orion spacecraft perched at its apex. In just two days, Orion would soar upward, completing a nearly flawless maiden flight. Bolden, 69, acknowledged that he may not live to see it, but his kids and grandkids would watch humans walk on Mars in the 2030s.

This moment captured the essence of Bolden’s leadership of NASA during the presidency of Barack Obama. Aspiration. Emotion. And, at times, a softening of reality. For while Bolden has spoken often about leading NASA to Mars, he rarely talks of the costs. NASA will spend $20 billion alone just to develop the Orion spacecraft. And Orion isn’t going to Mars. It’s a capsule to come back from the Moon.

Bolden hasn’t really leveled about two basic truths regarding Mars: it will cost a hell of a lot of money to do it NASA’s way, and it’s going to take a commitment like the nation hasn’t seen since the Apollo program. NASA presently has neither the money nor the commitment from Washington. Many who grasp the challenges of actually going to Mars, including those on the inside, realize this. “I can tell you that my colleagues, at least 90 percent if not more, don’t really think we have a good plan,” one veteran astronaut, who hopes to fly again and therefore sought anonymity, told Ars. Inside the astronaut office they joke about the Journey to Mars. “I think we’ve almost done negative work in the last seven years,” this flier said.

Not everyone feels that way about NASA’s human spaceflight program during Obama’s presidency, but there are few who offer unqualified praise for the president. He just never really showed much interest in space. While Obama did propose bold changes early on to NASA, seeking to more closely align the agency's goals to funding levels, Congress objected and the president retreated almost immediately. He chose to invest his limited political capital in other areas, effectively ceding most power over NASA’s human spaceflight programs to a Congress largely driven by parochial interests. And when an agency needs a unified purpose and the means to achieve it, this is rarely a formula for success.

Obama’s policy

Barack Obama is pro-science. The Spock-like president has opened the White House lawn to science fairs and stargazing parties, and he made evidence-based policy decisions such as pushing for climate action. He has also occasionally given passing nods to space, such as when he invited astronaut Scott Kelly to his 2015 State of the Union speech.

Yet Obama campaigned to become president in 2008 on much more down-to-earth issues, like the end of US involvement in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, healthcare, and education. Most pertinent to space buffs, to pay for his ambitious K-12 education plan, Obama proposed “delaying the NASA Constellation Program for five years.” This was George W. Bush’s plan to build a large rocket, the Orion space capsule, and return to the Moon as a waypoint to Mars. At $4 billion a year, it constituted nearly a fourth of NASA’s budget. When the space shuttle retired, its funding was to double.

-

How did our space policy get to where it is today? We look at the key players during the administration of President Barack Obama.NASA

-

Obama chose four-time astronaut Charles Bolden as NASA's administrator. Bolden has embraced the Journey to Mars but has not said how much it will cost or how NASA will pay for it.NASA

-

NASA Deputy Administrator Lori Garver, speaking to shuttle commander Chris Ferguson, sought to make sweeping changes to NASA in 2010 by turning over rocket building entirely to private companies and allowing the space agency to focus on innovating spaceflight technology. She left NASA in 2013.NASA

-

Florida Sen. Bill Nelson, although a Democrat, is involved in space policy under Trump. He spearheaded a "compromise" that allowed NASA to continue building large rockets. The Senate wrote the specs for the Space Launch System, leading some to dub it the "Senate Launch System."NASA

-

Texas Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison was the co-leader of the compromise with Nelson. She felt NASA would lose essential capabilities without an SLS-like program. She also tried without success to keep the space shuttle flying beyond 2011.NASA

-

Alabama Senator Richard Shelby: Chief supporter of the SLS rocket in the Senate. Responsible for setting NASA's budget in the U.S. Senate.NASA

-

Maryland Senator Barbara Mikulski has worked to make sure that other areas of NASA's budget, including the costly and oft-delayed James Webb Space Telescope, have received ample funding.NASA

-

Elon Musk, of SpaceX, has benefited from NASA contracts to develop commercial cargo and crew services. His company could almost certainly develop a lower-cost large rocket than the SLS, but the Senate wanted no part of that.NASA

-

Mike Griffin, NASA's administrator under George W. Bush, wanted to remain in that position for Obama. But the president rejected Griffin's Constellation plan—and Griffin himself. He remains influential behind the scenes.NASA

-

John Holdren, President Obama's science adviser and director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, has favored Earth science over human spaceflight.NASA

-

Bill Gerstenmaier, who has overseen NASA's human spaceflight programs since 2005, has tried to make the best of the Orion capsule, the SLS rocket, President Obama's grand goal of Mars, and limited funding.NASA

One year into his presidency, Obama was as good as his word. After convening a blue-ribbon panel led by former Lockheed Martin Chairman Norm Augustine, Obama concluded NASA was on an unsustainable course. Constellation had run badly over budget and behind schedule as NASA attempted to exceed the ambitions of Apollo with a comparatively smaller budget. When Bolden released NASA’s new budget in February 2010, it ended funding for Constellation. Instead, NASA would spend five years investing in advanced technology before choosing what systems to build for deep space exploration. Also to replace the shuttle, NASA would rely on private companies like SpaceX to develop less costly transport to low-Earth orbit.

Congress hated the plan, which removed power and money from NASA’s principal human spaceflight centers in Florida, Texas, and Alabama. Already wary of the space shuttle’s looming retirement, senators from those states fought back. They wanted a big rocket, and they wanted it built by contractors who would lose contracts after the shuttle ended. So Boeing, which managed the shuttle orbiters, got a contract to build the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket’s core stage. ATK, which made solid rocket boosters for the shuttle, would continue making them for the SLS. Aerojet Rocketdyne, which made the shuttle’s main engines, would continue doing so for the SLS. NASA has sold this rocket design as sensible, because it relies on proven hardware. But the principal motivation in Congress seems to have been turf protection and taking care of large contractors.

President Obama caved pretty quickly. Six years ago this Friday, just two months after his budget release, he flew to Kennedy Space Center and delivered his first and only space policy speech. He agreed to keep the Orion spacecraft, speed up development of a heavy lift rocket, and send humans to Mars (at least on flybys) in the mid-2030s. And, in a rhetorical flourish that dismayed much of the space community, he removed the Moon as a possible destination. “We’ve been there before,” Obama said.

Not all were happy to see his original plan go. In some ways it anticipated the development of lower-cost reusable rockets by SpaceX and Blue Origin. NASA almost certainly could have bought launch capability for a much lower price off the shelf. “The president’s original plan was a well conceived plan,” said John Logsdon, a noted space historian and author. “If there was a long term commitment to space exploration, spending five years investing in advanced technology before deciding what systems to build was a good idea. In its wisdom the Senate rejected the plan.”

The Senate compromise, Logsdon said, offered a mixed blessing. Yes, it used old technologies, and NASA was forced to underinvest in long-term exploration technologies like new propulsion systems. But it did, at least, represent a semblance of a path forward. And as Congress wanted, it kept a large aerospace workforce engaged in rocket and spacecraft design. What is almost unprecedented in the history of NASA, Logsdon said, is that after this initial battle Obama largely left the House and the Senate with the power to direct NASA’s human space plans through their budget-writing processes. “I think space was just not a high enough priority to use up his limited political credit with Congress to fight for,” Logsdon said. “I think he viewed in 2009 and the first half of 2010 the opportunity for policy innovation, but the reaction out of Congress convinced him that space, rather than being an opportunity, could be a problem.”

As NASA worked through the policy implications of building a big rocket on a budget, it searched for a justification. It settled on the Journey to Mars. Almost everything NASA did became part of this. Even last summer, when the grand piano-sized New Horizons whizzed by Pluto and sent stunning images of the world back to Earth, Bolden said it represented “one more step” on the Journey to Mars.

reader comments

132