The Problem With Public Sector Unions—and How to Fix It

Here's a plan to preserve the ability of government workers to bargain collectively -- one that would prevent the excesses that are destroying some communities' fiscal health.

With public employee unions suffering high-profile election losses in Wisconsin, San Jose, and San Diego, there is rampant speculation about what comes next. Noah Millman argues that voters and public sector unions have an inherently adversarial relationship. Says Will Wilkinson, writing in The Economist, "measures limiting the power of public-sector unions to organize against taxpayers are controversial, but not as politically dangerous as Democrats would like."

Suffice it to say that we're years away from any stable, widely accepted equilibrium. As Natasha Vargas Cooper put it some months ago in Slake, "A critical tactic in the conservative drive to build a permanent majority in Wisconsin and other Rust Belt states is to bust the unions under the guise of 'emergency' austerity measures. Walker's plan cuts right to the marrow of a labor movement that he, and just about everybody else, thinks is tottering on its heels. If it dies, one of the last major funding sources for Democrats dies, too." It is very thorny to tease out the motivations of partisans on this subject, because it's just a fact that strong public employee unions hurt the electoral chances of Republicans and help to fund and elect Democrats. It's also true that lots of states and localities are going broke due to pension obligations.

Before this post is through, we'll set aside the question of which political party benefits from the rules that govern public employee negotiations, and grapple with what the rules ought to be. But I want to share a story first, for it powerfully shaped my understanding of public sector unions. Prior to becoming a journalist, they weren't ever on my radar. But that changed at my first job. When I started as a newspaper reporter in Rancho Cucamonga, Calif., the suburban municipality had a population of roughly 128,000 people. It was 2002, a time when firefighters were at the height of their post-9/11 popularity. In the course of my reporting, I got to know several of the guys on the force. Generally speaking, they were a good bunch of people, and I was able to see them at their best, having arranged a 24-hour ride along weeks in advance that happened to occur on the day of the biggest fire that the community had seen in a generation.

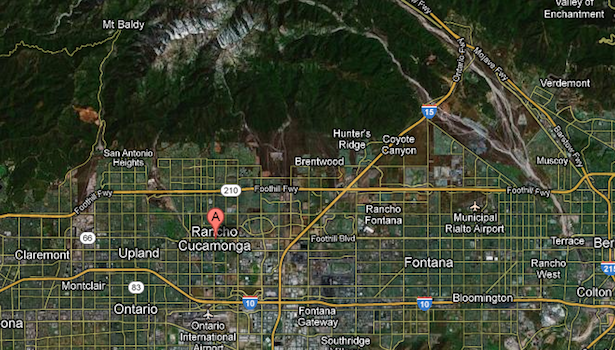

To understand the goodwill that these firefighters soon enjoyed, it's helpful to see a map of the city. As shown below, it is in the foothills, and the Southern California housing boom had pushed development right up to the edge of nature and in some cases beyond it. On the day in question, an enormous brush fire had burned throughout the day on the other side of the mountains.

Late that night, the wind suddenly shifted. Gusts drove the flames up the back side of the mountains, over the ridge, and down upon the city. The front of the blaze was miles wide. Thousands of homes were threatened. It was the fire for which everyone on the force had trained for years. Residents gathered at shelters in the southern part of the city, mesmerized by the spectacle. I was able to drive around in the evacuation zone. The smoke was suffocating. On the eastern edge of the city, old eucalyptus wind-rows would catch fire and the trees would explode from all the oil in the leaves. In the north, the firefighters executed what they called a bump and run strategy: race north on the streets that dead-ended in wilderness; let the flames burn to the edge of the houses, consuming all fuel; put them out; disconnect the hoses, race down the hill; go a few blocks over; race back up a different street to the edge of the wilderness, and repeat. The tops of those streets were as intense an environment as I'd ever seen. The heat was intense, the sky dark grey with flashes of apocalyptic orange, and the fire creating its own hellish wind. And the vast majority, if not all, of the firefighters were ready to risk their lives to save a life.

The firefighters' union in Rancho Cucamonga probably had a salutary effect on the force's performance. Its political clout counterbalanced the building interests that wielded a lot of influence in the city, leading to building codes that demanded more fire safety measures than would've been included otherwise. High salaries and generous benefits attracted high quality employees. And the union was always pushing for more stations, engine companies, and firefighters. It also looked out for the safety of the firefighters. The job is inherently dangerous, but protocol, equipment and training all have an impact on how many men are injured or killed while on duty. Finally, the compensation package negotiated by the union permitted many of the firefighters to live in the city where they worked, despite the fact that it was relatively expensive.

Over the next couple years, I nevertheless came to see the several downsides of the union's influence. Contract negotiations were held in private, with the City Council representing Rancho Cucamonga residents and union reps representing the firefighters. This posed a structural problem, for the interests of elected officials weren't particularly aligned with the public, whereas the union negotiators had a personal stake in whatever compensation package was adopted. To be more specific, if a City Council member behaved in a fiscally irresponsible manner, it wouldn't matter for at least a few years, by which time ambitious pols would have moved on to a county post or the state legislature. And lavish compensation packages could easily be obscured by combining what appeared to be a reasonable salary, the only number the public was likely to hear, with exorbitant pay for overtime or over the top fringe benefits.

But if a City Council member crossed the fire union? The consequences were immediate. As soon as the next election rolled around, they'd face a well-financed challenger. On his campaign mailers, he'd be photographed flanked by handsome firefighters. On weekends, friendly guys in fire-coats would go door to door on behalf of their would be champion. "We're very concerned that Councilman X is endangering public safety by refusing to do Y," they might say. Or else, "Challenger Z is a crucial ally in our effort to make this city safer." The incentives were clear.

The union also negotiated contracts that protected firefighters who misbehaved, even in egregious ways. The frat-house atmosphere common in firehouses was thus more pronounced than was ideal. And the weakest links on the force were weaker than they would've otherwise been, which matters, considering that these guys daily speed down busy streets, and regularly face situations where marginal differences in skill and judgment are the difference between life and death.

What I saw in Rancho Cucamonga helped me to understand, long before most people, what was happening in California generally. Under Gray Davis, the Democratic governor who was recalled by voters, the state's public safety employees got a pension deal that would make anyone drool: they could retire at age 55 and earn 90 percent of their final salary every year for life. That change put pressure on every municipality in the state to adopt the same deal for its police and firefighters. During the dot-com boom, state pension funds were flying high and officials made commitments in contract negotiations that were sustainable only if the boom lasted forever. For a while, cities got away with giving employees sweetheart pension deals, even as the payments they owed the state pension fund stayed low, for the fund was making money in the stock market.

But the boom ended. The economy during the aughts was never growing as fast as it had. And now, since the financial crisis hit, cities all over California are deep in the hole, some on the edge of bankruptcy. Wealthy, reasonably well-managed cities like Rancho Cucamonga face a fiscal environment where public employee compensation, especially for retirees, consumes a bigger and bigger portion of revenue every year, so that making good on the deals agreed to in better times makes residents less safe, for it means laying off police and firefighters, letting street repairs slide, cutting back on code enforcement, reducing social services, or otherwise cutting corners.

Other cities have it significantly worse.

Take San Jose, a city that just handed its public employees an electoral defeat. In "California and Bust," Michael Lewis visited its mayor, Chuck Reed, a popular Democrat with "a master's degree from Princeton, a law degree from Stanford, and a lifelong interest in public policy" who was reelected in 2010 with 70 percent of the vote. He's the sort of figure who shows that, whatever you think of Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, an ideological antagonism toward unions is not motivating every reform effort. Says Lewis, describing in detail the situation Reed faced (emphasis added):

Over the past decade the city of San Jose had repeatedly caved to the demands of its public-safety unions. In practice this meant that when the police or fire department of any neighboring city struck a better deal for itself, it became a fresh argument for improving the pay of San Jose police and fire... For instance, back in 2002, the San Jose police union cut a three-year deal that raised police officers' pay by 18 percent over the contract. Soon afterward, the San Jose firefighters cut a better deal for themselves, including a pay raise of more than 23 percent. The police felt robbed and complained mightily until the city council crafted a deal that handed them 5 percent more premium pay in exchange for training to fight terrorists. "We got famous for our anti-terrorist-training pay," explains one city official. Eventually the anti-terrorist-training premium pay stopped; the police just kept the extra pay, with benefits. "Our police and firefighters will earn more in retirement than they did when they were working," says Reed. "There used to be an argument that you have to give us money or we can't afford to live in the city. Now the more you pay them the less likely they are to live in the city, because they can afford to leave. It's staggering. When did we go from giving people sick leave to letting them accumulate it and cash it in for hundreds of thousands of dollars when they are done working? There's a corruption here. It's not just a financial corruption. It's a corruption of the attitude of public service."

When he was elected to the city council, Reed says, "I hadn't even thought about pensions. I can't say I said, 'Here is my plan.' I never thought about this stuff. It never came up." It wasn't until San Diego flirted with bankruptcy, in 2002, that he wondered about San Jose's finances... He hands me a chart. It shows that the city's pension costs when he first became interested in the subject were projected to run $73 million a year. This year they would be $245 million: pension and health-care costs of retired workers now are more than half the budget. In three years' time pension costs alone would come to $400 million, though "if you were to adjust for real life expectancy it is more like $650 million." Legally obliged to meet these costs, the city can respond only by cutting elsewhere. As a result, San Jose, once run by 7,450 city workers, was now being run by 5,400 city workers. The city was back to staffing levels of 1988, when it had a quarter of a million fewer residents. The remaining workers had taken a 10 percent pay cut; yet even that was not enough to offset the increase in the city's pension liability. The city had closed its libraries three days a week. It had cut back servicing its parks. It had refrained from opening a brand-new community center, built before the housing bust, because it couldn't pay to staff the place. For the first time in history it had laid off police officers and firefighters.

By 2014, Reed had calculated, a city of a million people, the 10th-largest city in the United States, would be serviced by 1,600 public workers. "There is no way to run a city with that level of staffing," he said. "You start to ask: What is a city? Why do we bother to live together? But that's just the start." The problem was going to grow worse until, as he put it, "you get to one." A single employee to service the entire city, presumably with a focus on paying pensions...

In his negotiations with the unions, the mayor has gotten nowhere. "I understand the police and firefighters," he says. "They think, We're the most important, and everyone else goes [gets fired] first." The police union recently suggested to the mayor that he close the libraries for the other four days. "We looked into that," Reed says. "If you close the libraries an extra day you pay for 20 or 30 cops." Adding 20 more police officers for a year wouldn't solve anything. The cops who were spared this year would be axed next, in response to the soaring costs of the pensions of city workers who already had retired.

San Jose isn't unique. There are California cities in even worse straits. City officials are asking themselves questions like, "What is more sacrosanct, the pension promises past elected officials made to police and firefighters, or the ability to continue paying enough staffers to put out fires, pick up trash and keep the library open?" That is why the unions lost in San Jose. Most voters were deciding between significant hits to their quality of life, or cutting the pension benefits of people who earned much more than they did and would earn much more in retirement.

Alongside the mathematical fact that there isn't enough money to meet the obligations many states and cities have taken on, there are the many instances of public employees misbehaving in the most egregious ways, but staying on paid leave or even on the job due to the protections negotiated by their unions. At U.C. Davis, the police officer who pepper-sprayed student protestors couldn't be forced to testify in the official inquiry, nor could he be summarily fired when an independent investigator found him at fault. The Los Angeles Times has documented how costly and time consuming it can be to fire even the worst teachers, when they can be ousted at all.

An example:

The eighth-grade boy held out his wrists for teacher Carlos Polanco to see. He had just explained to Polanco and his history classmates at Virgil Middle School in Koreatown why he had been absent: He had been in the hospital after an attempt at suicide. Polanco looked at the cuts and said they "were weak," according to witness accounts in documents filed with the state. "Carve deeper next time," he was said to have told the boy."Look," Polanco allegedly said, "you can't even kill yourself."

The boy's classmates joined in, with one advising how to cut a main artery, according to the witnesses. "See," Polanco was quoted as saying, "even he knows how to commit suicide better than you." The Los Angeles school board, citing Polanco's poor judgment, voted to fire him. But Polanco, who contended that he had been misunderstood, kept his job. A little-known review commission overruled the board, saying that although the teacher had made the statements, he had meant no harm.

These bad apples are unusual, and shouldn't be presumed to represent public employees as a whole. But it's public sector unions who defend those employees, and who put in place protocols that makes it very hard to fire them. Unions and the employees they represent bear responsibility for that.

California's prison guards highlight another potential problem with public employee unions -- conflicts of interest that distort public policy making. The prison guard union's members have an interest in more people being in prison, and so they've used their dues to lobby for policies that help to explain why the incarceration rate in California has skyrocketed. It is suboptimal for these powerful government-funded entities to lobby in favor of policies because they'll benefit as a special interest, especially when the policies are as consequential as is criminal law.

It's absolutely true that Republicans want to dismantle public employee unions partly because it'll help them electorally. But when you reflect on the ideological interest that Democrats have in a public school system that functions well, a prison system that incarcerates fewer people, and municipalities where there's enough money to fund libraries, parks and recreation, and other public goods, their failure to rein in even the most egregious public-employee-union-backed excesses sure makes it seem like they are no less motivated by base electoral calculations.They're even sacrificing public perception of how effective government can be in the process.

Which brings us back to what the rules ought to be. As I see it, the status quo is clearly untenable. I am not ready, however, to outlaw all public employee unions. Instead, I'd preserve the right to bargain collectively while limiting the scope of that right. Public employees unions should be able to negotiate compensation packages, but only the total amount of compensation owed each employee for a period no longer than an election cycle, which would make the costs a lot more predictable and transparent, and build political accountability into the process. As a nudge, the package would be structured, by default, with prudent percentages going to health care and retirement savings, but if the union or the individual employees wanted to override that mix, it would be their business. The municipality would only be in the business of negotiating the total amount it allocates up front to compensate an employee for a given year.

Public employee unions could also negotiate for improved job safety, a core good unions facilitate. But not for job security or seniority requirements (though government employees would enjoy all of the protections against wrongful termination from which folks in the private sector benefit). Especially when it comes to public safety employees and teachers, it's vital that the worst can be fired easily. The public's welfare must be a more urgent priority than job protections so robust that they jeopardize it. (Wrongful termination in the private sector is hardly a huge problem.)

These several reforms address the most problematic effects of public employee unions that we've observed in the real world, while preserving the ability of government workers to negotiate collectively for better compensation, and when necessary, to address safety issues pertaining to their jobs. They are neutral on the question of how much public employees ought to be paid. And they give elected officials greater flexibility to grapple with the changing finances of their jurisdictions. Surely that's at least an improvement over a status quo that is bankrupting many.