Inflammation has become one of the hottest buzzwords in medical science, pointed to as a culprit in causing or aggravating conditions ranging from allergy to autism to Alzheimer’s disease.

But it’s far from clear that standard anti-inflammatory drugs, which have been around for decades, will help patients with those conditions, especially since they often come with dangerous side effects. So in labs across the country, scientists are trying to puzzle through the basic biology, understanding how inflammation leads to disease — and whether it’s possible to develop drugs that could interrupt that process.

The latest evidence of inflammation’s broad role in disease came this past week, when a global clinical trial of 10,000 patients who had previous heart attacks showed that an anti-inflammatory drug from Novartis reduced their risk of further heart attacks or strokes. A surprise side effect: The drug also sharply cut the risk of lung cancer.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

That finding still needs to be confirmed with more research. But lead investigator Dr. Paul Ridker, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said he saw the trial as a clear indication of inflammation’s role in spurring cancer growth. The results, he said, turn “the way people look at oncology upside down.”

Although inflammation has been studied for decades, there’s still a lot left to learn about this complex physiological condition. It’s basically an unnecessary state of hyperactivity in the body, in which the immune system’s reserve capacity is thrown into overdrive. This excess immune activation sends the wrong cellular signals to various parts of the body — and can wind up worsening conditions like diabetes, Alzheimer’s, and potentially even cancer.

“Inflammation wastes your energies and wastes your [immune system] reserves, which are usually needed and required and restricted for acute situations like injury and infection,” said Dr. Irini Sereti, chief of the HIV pathogenesis division at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

But preventing disease isn’t as simple as quelling inflammation.

Anti-inflammatory drugs have predictable and dangerous side effects, which showed up in the recent trial of the Novartis drug canakinumab in patients with cardiovascular disease. Some patients involved in the trial wound up becoming more susceptible to serious infections, such as the bacterial skin infection cellulitis, the deadly blood infection sepsis, and even tuberculosis. That’s because a the body relies on inflammation to trigger the immune system to fight such invaders. Tamp it down too much and the immune system may not leap to your defense.

“The problem is if you block inflammation, you’re blocking a primordial mechanism by which we are protected from the organisms that share the planet with us,” said Dr. Clay Semenkovich, chief of endocrinology, metabolism, and lipid research at Washington University in St. Louis.

Yet another hurdle: Every individual responds differently to anti-inflammatory drugs, based in part on their genetic makeup. And each drug targets a different aspect of the many inflammatory pathways in the body.

Some work like “sledgehammers,” ratcheting down inflammation across the board and thus leaving the patient more susceptible to infection, said Dr. Sanjay Jain, director of the Center for Infection and Inflammation Imaging Research at Johns Hopkins University.

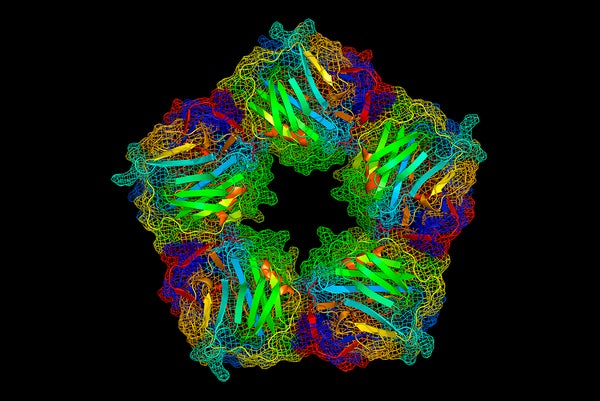

Others, like canakinumab, work on a more targeted portion of the inflammatory pathway — focusing specifically on interleukin 1-beta, a cell-signaling protein that helps kick off the immune response. Those proteins are made by macrophages — white blood cells programmed to attack infections and other foreign bodies. The drug prevents these cells from going into overdrive, but presumably leaves the remaining immune system intact.

“What’s exciting is that we’re starting to see a diversification and specification of treatments that go after these inflammatory pathways,” said Dr. Alex Marson, an immunology researcher at the University of California, San Francisco.

Here’s a look at a few of the conditions where inflammation plays a key role — and how researchers hope to tackle them.

HIV: Bits of virus tickle the immune system

People who have HIV and are being treated with standard antiretrovirals are often extremely successful at keeping their infection at bay. All the same, residual bits of virus continue to float in their bloodstream — and constantly “tickle the immune system, increasing chronic inflammation,” Sereti said.

Over time, this inflammation causes excess blood clotting — and ultimately doubles their risk for cardiovascular disease.

NIAID is conducting a pilot study in primates, using a drug derived from tick saliva meant to prevent the blood from clotting. (Ticks and other such insects have natural anti-coagulants in their saliva to make it easier for them to drink and digest the blood they rely on for nourishment.)

The research, just published in Science Translational Medicine, found that the drug managed to tone down abnormal blood clotting and immune activation. Researchers now hope to test this tick saliva drug further, to ultimately create a drug that might not only be useful for the clotting and inflammation seen in HIV, but in a number of other diseases — such as the hemorrhaging that takes place in Ebola.

Diabetes: Treatment is a tricky balancing act

Diabetes is thought to be a consequence of chronic, low-grade inflammation, which appears to change the way glucose is absorbed by cells.

Anakinra, a biologic anti-inflammatory drug, has been found to improve some diabetes symptoms by blocking the cytokine protein Interleukin-1 — a key instigator of the immune and inflammatory response.

But there’s a tricky balancing act here. Commonly prescribed steroids, such as prednisone, are among the most potent anti-inflammatory drugs on the market — but they have been found to spike blood glucose levels, and chronic use can even meddle with a body’s ability to use insulin over the long term. So they’re not feasible to use as a treatment for diabetes.

So Semenkovich has been exploring how diabetics break down fats and other lipids. Most diabetics don’t metabolize lipids properly — leading to fluctuations in lipid levels that can spur inflammation.

One tantalizing clue: Macrophages seem to encourage inflammation. So when Semenkovich’s team interrupted the ability of mouse macrophages to make fat, “it actually strikingly suppressed its ability to carry out inflammatory signaling,” he said.

Such work contributes to the basic science understanding of diabetes, but drug development based on this work is still far off.

Alzheimer’s: tantalizing clues, but still no answers

Labs across the country have been racing to unravel the role of inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS.

One possible hint comes from work done at Columbia University by neuropsychologist Yian Gu. She found last year that certain nutrients can work to protect the brain, while one — cholesterol — seemed to accelerate brain aging. Gu’s team found greater signs of inflammation in patients who ate fattier diets.

“We found that people with more pro-inflammatory nutrient patterns have smaller brain volumes and worse cognition,” she said. (Her subjects were healthy, with no signs of dementia.)

Other studies implicate a buildup of immune cells in the brain, saying the subsequent inflammation causes neurological dysfunction.British researchers last year found that a drug blocking the production of microglial cells — which are part of the immune system — had a positive effect on brain function, at least in mice. Scientists at the Salk Institute in San Diego also found this year that the genes linked to neurological diseases are turned on at higher levels in the microglial cells.

But while this may seem like a promising avenue for drug development, there are inherent risks in targeting the immune cells in the brain.

Exhibit A: The case of natalizumab — a biologic drug used to treat both Crohn’s disease and multiple sclerosis. It effectively prevented inflammation of the central nervous system by blocking certain immune cells — such as T cells and natural killer cells — from making their way into the brain.

But it had an unintended side effect: It made patients far more susceptible to a deadly virus that lies quiescent in the brain, kept in check by the immune system.

“If you block the ability of these immune cells to get inside the brain, you might medicate some of the problems of multiple sclerosis,” said Larry Pease, director of the research center for immunology and immune therapies at Mayo Clinic. “But those same cells regulate viral infection — and caused some serious unintended consequences.”

Depression: a surprising link to inflammation

Depression is a surprising focus of study for brain inflammation, but a battery of recent studies have shown that these patients often have high levels of inflammatory markers in their system. As an example: A pro-inflammatory drug once used for hepatitis C was found to cause depression in some 40 percent of people who took it.

Johnson & Johnson recently sponsored a large clinical trial, enrolling patients with major depressive disorder to test out an experimental biologic drug, called sirukumab, which blocks an inflammatory protein. The drug, initially tested for rheumatoid arthritis, showed an interesting side effect in clinical trials: It seemed to improve patient’s moods.

A major caveat, though: Sirukumab was snubbed by a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel this summer; arthritis experts on the panel voted 12 to 1 against approving the drug because it led to several deaths from cardiovascular disease and serious infection.

That finding again underscored the risk of targeting inflammation: These are complex pathways and will take extraordinary fine-tuning to make sure medical treatments are as safe as they are effective.

Heart disease: a drug shows promise in a global trial

Still, there are other promising trials underway that more closely examine inflammation — particularly in the cardiovascular space.

Ridker, who conducted that 10,000-patient trial, has a second related trial underway — testing out a long-used immunosuppressive drug, methotrexate, in tamping down inflammation in heart disease. The rationale? Canakinumab, which has shown some impressive efficacy, is a costly medication, running about $16,000 for a course. Methotrexate, by contrast, costs about $120 when used to treat arthritis.

In this second trial, patients who previously had heart attacks are given low doses of methotrexate, and evaluated to see if its anti-inflammatory effect will lessen the recurrence of cardiovascular disease. These patients will also be tracked to see if lowering inflammation will decrease their likelihood of developing cancers.

“We have no way of knowing whether methotrexate or canakinumab will do better in trials,” Ridker said. “I just wanted two swings at the bat for my inflammation hypothesis.”

Republished with permission from STAT. This article originally appeared on August 31, 2017