Why Are So Many Americans Dying Young?

A new pair of studies show why—and where—American life expectancy has grown worse in a generation.

For the first time since the 1990s, Americans are dying at a faster rate, and they’re dying younger. A pair of new studies suggest Americans are sicker than people in other rich countries, and in some states, progress on stemming the tide of basic diseases like diabetes has stalled or even reversed. The studies suggest so-called “despair deaths”—alcoholism, drugs, and suicide—are a big part of the problem, but so is obesity, poverty, and social isolation.

American life expectancy fell by one-tenth of a year since 2014, from 78.9 to 78.8, according to a report released last week by the National Center for Health Statistics. As The Washington Post reported, the last time the life expectancy went down instead of up was in 1993, during the throes of the AIDS epidemic. Meanwhile, the number of years people are expected to live at 65 remained unchanged, suggesting people are falling ill and dying young.

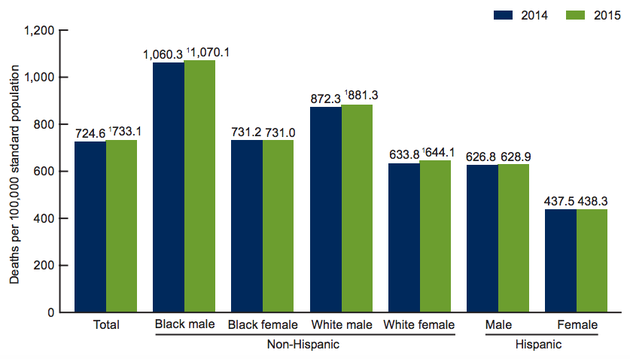

The overall death rate rose by 1.2 percent in 2015, the first time since 1999. The death rates went up for white men and women and for black men, but did not change significantly for Hispanics or black women.

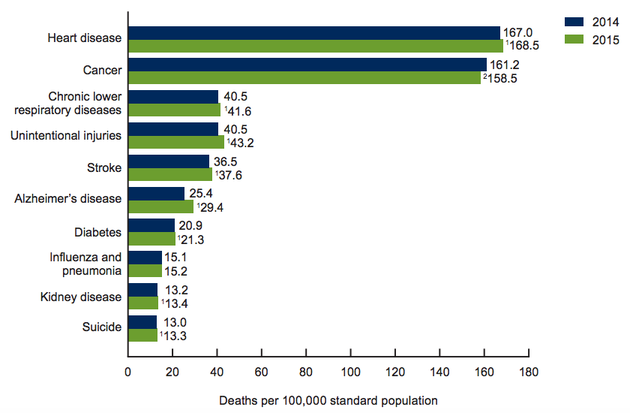

Heart disease and cancer were the most common causes, accounting for nearly half of all deaths. Still, cancer deaths are declining, while deaths from all other causes, including heart and lung diseases, strokes, Alzheimer's, diabetes, and suicides have ticked up:

Deaths from unintentional injuries, including drug overdoses, are also up, rising by 10,000 since 2014. While the epidemic of heroin and prescription-painkiller abuse accounts for some of that, experts say it doesn’t explain the full picture.

“If it was all about opioids, we might focus our efforts on [that issue],” said Ellen Meara, a professor at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. “But we see that strokes, heart disease, and chronic lower respiratory disease deaths are rising as well, suggesting the problem is even more widespread than we thought.”

Much of the increase in mortality can be explained by obesity. In 2015, weight problems accounted for more than 10 percent of all American deaths, according to Christopher Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, but just 7 percent in the U.K. and 3 percent in Japan.

However, poverty and its associated struggles, such as depression, stress, and poor nutrition, are also clearly playing a role.

“We might be seeing the drag that decades of stagnant wages, growing inequality, and the associated behavioral (e.g. smoking, diet, activity) and psychosocial (e.g. chronic stress, depression) factors have on eventual mortality,” said Michael Kramer, a professor of epidemiology at Emory University, via e-mail. Americans are hit harder than other rich countries are by these forces, he posits, both because of our skimpy preventive health care and because “the U.S. has higher income inequality and less comprehensive social safety net, so the ill-effects of poverty may take an undo toll.”

One paper published this month suggested that Americans would live nearly four years longer if the U.S. had a safety net as generous as those of European countries.

The increases in mortality vary by gender, ethnicity, and region of the country. For example, Meara said, white women are increasingly dying of chronic lower respiratory diseases, such as emphysema, while black men are increasingly dying in homicides.

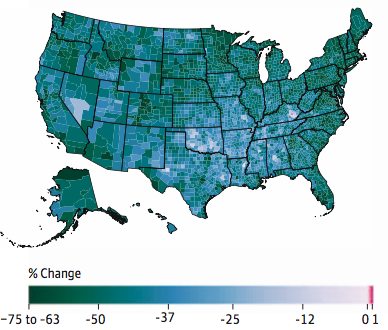

A study co-authored by Murray, of the University of Washington, and published in the Journal of the American Medical Association Tuesday shed more light on state-by-state variance in mortality. It showed that though deaths from some ailments have declined in the U.S. since 1980, progress has been geographically uneven.

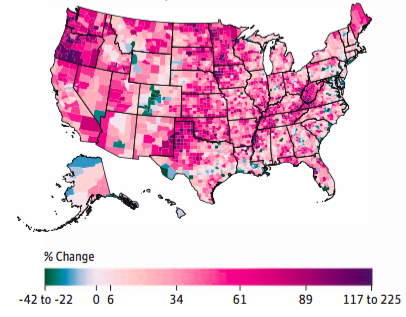

from cardiovascular diseases between 1980 and 2014 (JAMA)

The study authors found mortality rates from diabetes, neurological disorders, respiratory diseases, and substance-use disorders all rose from 1980 to 2014. But even diseases that have improved overall are still killing thousands of people every year in pockets of the country. Deaths from heart-disease declined by 50 percent in the U.S. overall since 1980, for example, but southern states have not improved much. In parts of Appalachia, more people are dying of heart disease now than were in 1980, despite rapid improvements in medical technology. (Murray’s study also suggests the report from the National Center for Health Statistics represents a stagnation in progress on heart-disease mortality, since his paper only tracks deaths through 2014.)

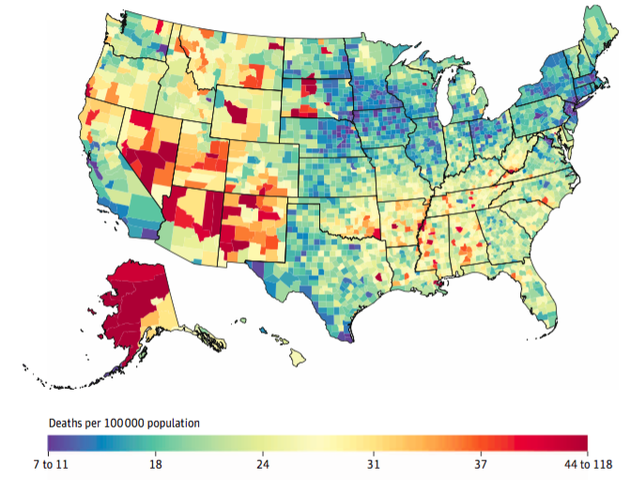

from diabetes, urogenital, blood, and endocrine diseases between 1980 and 2014, both sexes (JAMA)

“A place like Colorado, there’s an incredibly low death rate for heart disease, one of the lowest in the world, and low rate for diabetes,” Murray said. “If you look at places like West Virginia, things are getting worse, and it’s not just opioids.”

Deaths from self-harm and interpersonal violence went down nationally since 1980, Murray found, but that improvement is most noticeable in the northern states and Texas. Many western states are still struggling with an epidemic of gun suicides.

“People in small, rural communities can often get more isolated and have less social support,” Murray said, “and these are communities where the means to harm yourself are more readily available.”

Murray suggests his study could be used by county health departments, physicians, and researchers to target specific interventions toward communities that need them.

Nationally, better health-care access could improve mortality rates. But if Obamacare is repealed, 30 million Americans might lose their health insurance coverage as early as January—unless, of course, a better plan comes along.