Scientists have grown a replacement, genetically modified skin to cover almost the entire body of a seven-year-old Syrian boy who was suffering from a devastating genetic disorder.

The treatment marks a rare and striking success for the field of regenerative medicine, which has been struggling to transform futuristic-sounding science into therapies that make a difference to patients. In the latest trial, the life of the young boy – whose illness had come close to killing him – was transformed.

Before undergoing surgery, the boy had lost 80% of his skin, leaving him covered in untreatable, infected wounds. He was given morphine to cope with the pain and his doctors were preparing to start palliative treatment after all conventional therapies had failed.

Prof Cédric Blanpain, a stem cell scientist at the Free University of Brussels, described the work as one of the most impressive examples to date of the use of stem cells in humans. “There are very few diseases that have benefitted so far,” he said. “This is a beautiful example of something that was unthinkable before the study. To replace and gene-correct the whole skin of a patient is just amazing.”

Claire Higgins, a lecturer of bioengineering at Imperial College London, described the trial as “a huge achievement and quite remarkable”.

The boy, who arrived in Germany in 2013 after his family fled Syria as refugees, was suffering from a genetic disease called junctional epidermolysis bullosa, which causes the skin to become fragile and blister. By the time he came to be treated, he had lost the surface layer of skin, called the epidermis, from almost his entire body, with only the skin on his head and a patch on his left leg remaining intact.

His doctors, based at University Children’s Hospital, Ruhr University Bochum, had attempted to graft skin from his father, but the transplant had been rejected. As a last resort, the team sought the help of Italian scientists who had pioneered a technique to regenerate healthy skin in the laboratory – but had never attempted to use it for such an ambitious case.

The Italian team, led by Michele De Luca at the University of Modena, had successfully grafted laboratory-grown, genetically modified skin onto small areas of the body, such as part of a leg. “This is the first time that such an amount of body has been transplanted,” said De Luca. “He basically lost almost completely his epidermis.”

The boy’s disease was caused by a mutation in a gene, called LAMB3, that produces a protein that anchors the epidermis to the deeper layers of skin beneath. Without this protein the skin blisters easily, causing chronic wounds and ulcers to form.

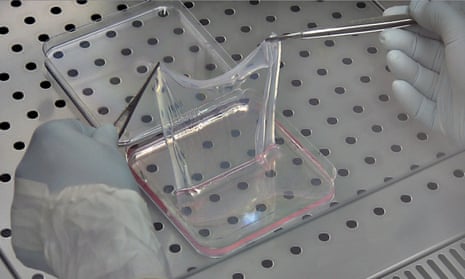

The treatment, outlined in a paper in the journal Nature, involved first taking a sample from the patient’s remaining healthy skin. The scientists then genetically modified these skin cells, using a virus to deliver a healthy version of the LAMB3 gene into the nuclei.

The skin contains its own supply of specialised stem cells, which allows the epidermis to be constantly renewed throughout our lives, with cells turning over roughly every month. This also allows scientists to grow grafts in culture, simply by taking a small sample.

In this case, the team grew enough skin to cover almost the entire body of the boy. During two operations in autumn 2015, the new epidermis was attached like a patchwork quilt, covering almost his entire body. Within a month, the graft had integrated into the lower layers of skin.

The genetically modified cells in the graft include specialised skin stem cells that meant once the transplant was integrated it was able to renew and sustain the healthy skin.

“Once you have regenerated the epidermis, the stem cells keep making the renewal of the epidermis as in a normal [healthy person],” said De Luca. “All the data we have … are telling us that this is going to be a stable situation.”

Two years on the boy is doing well, his doctors said. His skin is healthy, he doesn’t need to take medication or use ointments, he is back at school, plays football and when he gets a cut it heals normally. A potential risk of the treatment is that the introduction of genetic changes could increase the chances of skin cancer – although the study found no evidence that dangerous mutations had been caused.

In the future, if the treatment is shown to be safe in the long term, scientists believe the approach could be used to treat less severe skin disorders.

“What is nice about this study is the combination of gene and cell therapy together,” said Higgins, whose own work focuses on skin regeneration. “The success of this combined cell and gene therapy will have huge implications for the field of regenerative medicine and the treatment of genetic diseases.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion