Behind his counter in the Mercat de la Independència, a handsome modernista market that commemorates the centenary of the outbreak of Spain’s war of independence in 1808, Jaume Florensa is reflecting on an earlier, if equally fateful, year in national history.

Like many Catalans – about 41%, according to the polls – the poulterer is a passionate believer in sovereignty and a man with a memory that stretches back well beyond his 61 years.

He still rues the day, 303 years ago, when Barcelona fell to Philip V and the king went on to punish Catalonia for backing the wrong candidate in the war of the Spanish succession by suppressing its ancient freedoms and institutions.

“We’ve always felt we’ve had a raw deal – ever since 1714,” says Florensa, who was born and bred in Terrassa, a city half an hour’s drive from Barcelona.

“I suppose that makes it an old fight. As far as the top people in Madrid are concerned, Catalonia is a possession; we still feel like we’re the spoils of war.”

Florensa hopes all that will change in just under two weeks’ time. Catalonia’s pro-independence regional government, led by Carles Puigdemont, is adamant that Catalans will go to the polls on 1 October to vote in what it insists is a democratic and legally binding referendum on breaking away from Spain.

The secessionists argue that Catalonia has a moral, cultural, economic and political right to self-determination. They also feel their rich region of 7.5 million people has long put more into Spain than it has received in return. But the Spanish government says there will be no referendum because the vote would be illegal, unilateral and unconstitutional.

The showdown, which has seen the usual deep mutual suspicion between Barcelona and Madrid curdle into something far more toxic, is also splitting Catalans, almost 50% of whom favour staying as part of Spain.

One business owner in Terrassa quietly expresses the hope that Catalonia will remain part of Spain before swiftly refusing to elaborate or be named.

The city’s mayor, whose offices are a stone’s throw from the market, is also well aware of just how polarising the independence debate can be.

Jordi Ballart, a member of the Catalan Socialist party (PSC), which opposes the referendum, declined to be interviewed. His Facebook page, however, details the abuse he has suffered over his opposition to the vote.

“They’ve called me a quisling, a turncoat, a sellout, a coward, a wimp and a traitor … They’ve told me … I’m a bad Catalan, a moron, that I’m despicable, a piece of shit and a disgusting faggot – among many other things,” he wrote.

Núria Marín, the PSC mayor of Catalonia’s second most populous city, L’Hospitalet, is reported to have complained to Puigdemont about the pressure being brought to bear on her colleagues by some in the independence movement.

“I told him what a lot of people are thinking,” she told El País last week. “It hasn’t happened to me but a lot of my colleagues are having a rough time. Putting mayors in the crosshairs won’t fix anything; it’ll just add fuel to the fire.”

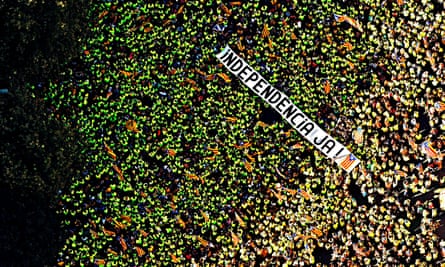

The apparent hectoring is in sharp contrast with the scenes in Barcelona a week ago, when up to a million people congregated in the Catalan capital to celebrate the region’s national day – la Diada – and to make another peaceful and good-natured call for independence.

A Spanish government official describes the referendum as a circus and claims Madrid has a democratic duty to protect the “silent majority” of Catalans who oppose independence and to make sure the dispute doesn’t descend into violence.

“It’s very important for a government to create a situation where there is a peaceful relationship among people, and this is not the case in Catalonia now,” he says.

The official defends the confiscation of more than 1.5m referendum leaflets and posters, saying they were part of an illegal poll and adding: “We always react with a cool head, [and in a] measured way; a proportional way.”

Such arguments are met with short shrift in Barcelona. According to a source in the regional government, if anyone is putting pressure on Catalan officials, it is the Spanish government.

Last Wednesday, Spain’s top prosecutor began investigating the more than 700 Catalan mayors who have agreed to cooperate with the vote, and has ordered police to arrest any who fail to appear for questioning. Madrid has also moved to take control of the region’s finances to prevent the funds being used for the referendum.

Meanwhile, Spanish Guardia Civil officers have raided local newspaper offices and printing shops in Catalonia. On Tuesday, officers investigating an alleged water supply fraud said to have taken place while Puigdemont was mayor of Girona raided the offices of a water company in the city.

“The Spanish government is showing its true, authoritarian face,” says the source. “They refuse to enter into dialogue or use politics to solve a political issue. They’re shirking their political responsibilities and are instead using judges, prosecutors and the police – who shouldn’t be playing any part in this.”

They liken Madrid’s actions to those of authoritarian regimes in countries such as Turkey, saying Spain is enduring “an Erdoğanisation” of its politics.

Last week, Ada Colau, the mayor of Barcelona – who has agreed to support the holding of the referendum – warned that the push for independence was excluding “half the people of Catalonia”.

Asked whether the vote could prove as divisive as the Brexit referendum has in the UK, the Catalan government source replies: “Democracy doesn’t divide; it’s the absence of democracy that divides people … We want people to vote – including the people who are going to vote no. If people have doubts, then 1 October is an opportunity for them to go to their polling station and put their vote in the ballot box.”

Alex Ramos, a doctor and the vice-president of Societat Civil Catalana, a group opposed to independence, is not persuaded by the regional government’s rhetoric. He also sees obvious parallels with the Brexit campaign.

“There’s a very clear analogy,” he says. “From our point of view, there’s a populist element in all this: you’ve got good people and bad people, you’ve got a victim mentality; and you’ve got a leader and his people.”

Ramos does not underestimate the desire that many Catalans have for independence, nor does he dispute the power of the Diada. But he does believe the Catalan government has taken advantage of old resentments and Spain’s economic crisis to stir up feelings of victimhood and further its own agenda.

How else, he asks, could support for independence have risen from around 15% in 2009 to 41% today?

“In that rise, there’s anger and economic crisis but there’s also propaganda,” he says.

Although Ramos is convinced the referendum will not take place, he knows both sides are “still going to go all out until the referee blows the whistle”. Whatever happens on, or after, 1 October, he adds, Catalonia’s body politic will need attention.

“We’re going to need to stitch up the wounds and build bridges and start talking more and talking better. We need to find a solution.”

But between Puigdemont’s promise to declare independence from Spain within 48 hours if the yes camp wins and the Spanish government’s refusal to rule out suspending Catalonia’s autonomy, solutions seem as remote as ever.

Mingled with the clamour and the manoeuvring, the accusations and the threats, is a feeling of weariness and deja vu; a sense that the issue routinely billed as Spain’s biggest crisis since its return to democracy four decades ago will once again fail to yield a payoff that is sufficiently neat or quick.

Antonio Barroso, an analyst at the political risk advisory firm Teneo Intelligence, says while modern Spanish history has been undeniably turbulent, the Catalan questions differs from the other shocks and scourges that the country has suffered over recent decades.

“We had Eta bombing the country every other day in the 80s; we had massive corruption cases in the 90s involving the head of the Guardia Civil; we had one of the biggest terrorist attacks on European soil in 2004, and we had a huge economic crisis.

“Yes, this is one of the biggest challenges to the territorial model established in the Spanish constitution after the transition to democracy, but it’s a political issue at the end of the day.”