Has North Korea Already Passed Trump's Red Line?

Kim Jong Un may have just tested the country’s longest-range missile yet.

Back in January, Donald Trump responded to Kim Jong Un’s claim that he was close to testing an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM)—the kind of long-range missile that, if fitted with a nuclear warhead, could deliver the world’s deadliest weapon to the United States. “North Korea just stated that it is in the final stages of developing a nuclear weapon capable of reaching parts of the U.S.,” the American president-elect tweeted. “It won’t happen!”

Trump’s national-security adviser later elaborated on what his boss meant. In an interview with Fox News in April, H.R. McMaster specified what might prompt the Trump administration to take the extremely risky step of using military force against North Korea. “I don’t think anyone thinks that it would be acceptable to have this kind of regime with nuclear weapons that can target, that can range the United States,” he said.

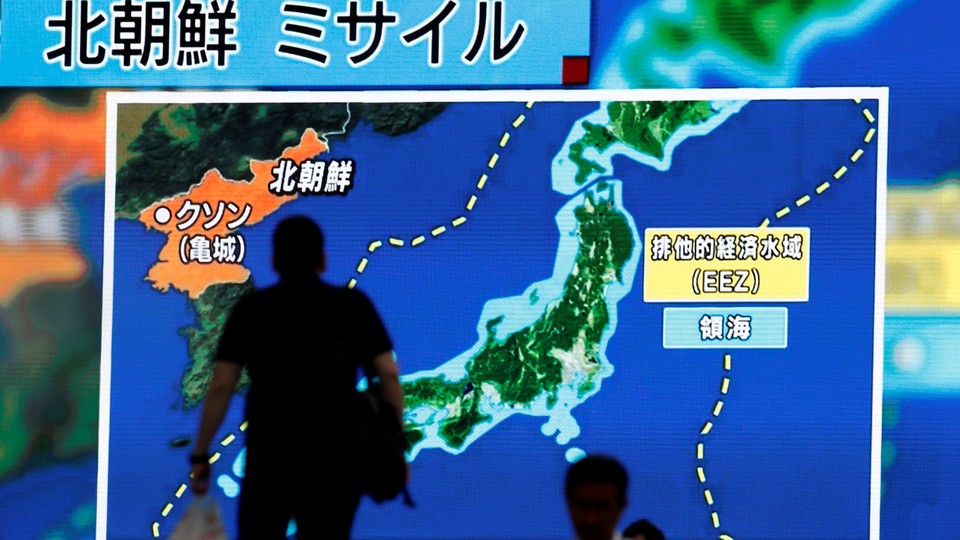

At the time of those remarks, experts were predicting that North Korea might acquire the capability McMaster feared within Trump’s first term in office. As recently as a few days ago, following North Korea’s first test of an ICBM in early July, The Washington Post was reporting on a U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency assessment suggesting that North Korea could reach that milestone within a year. But on Friday, North Korea successfully tested its second ICBM—this time sending a missile aloft for roughly 45 minutes, and 1,000 kilometers, before it crashed into the Sea of Japan.

And as details emerge about this latest ballistic-missile test, Melissa Hanham, an expert on the North Korean nuclear-weapons program at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies, has a response to Trump’s vow that what U.S. officials fear most from North Korea “won’t happen!” It has happened—or at least it may finally be time to start acting as if it has. She explains why below, in a conversation that I have condensed and edited for clarity.

Uri Friedman: I’ve seen your analysis that the missile North Korea just tested may have been longer-range than the last North Korean test of an ICBM, and potentially long enough to threaten U.S. cities like New York. Can you go into what’s behind that assessment and what the math is?

Melissa Hanham: Whenever a missile is launched, there are a few points of data that we immediately look for. One is where it was launched from, one is where it landed, the other is how high it went, and how long it took to fly. That data tends to trickle out pretty quickly from South Korean, Japanese, and American sources. Those numbers are still firming up right now.

When we analyzed the Hwasong-14 launch, [North Korea’s first test of an ICBM, on July 4], we were able to see that even though the missile only traveled just short of Japan, it went quite high up into the air, through the atmosphere, past the Space Station. That’s called a “lofted trajectory.” If you were to adjust that curve to the more energy-conserving range, toward the U.S., you would get a range that would put Alaska at risk.

However, we weren’t satisfied with just that number. When [the North Koreans] released photographs of the Hwasong-14, we did very careful measurements of each stage of the rocket, we made estimates of the fuel and oxidizer in each stage of the missile, the weight of each stage of the missile, and we did analysis of the video of the rocket launching to get a sense of the acceleration off the ground and therefore the thrust of the missile. And at that time we predicted that even though the test only showed [the missile] going about 7,000 kilometers, [the missile] was not tested to its full capability. In fact, we estimated that it would be more like a 10,000-kilometer range instead.

Friedman: What would a 10,000-kilometer range mean?

Hanham: Not just Alaska but all of the West Coast and most of the Midwest. So Chicago, Detroit.

Friedman: How does that compare to what we know so far about [today’s tested missile]?

Hanham: Today the data that’s coming in, which is still soft, is showing that along the ground, [the missile] went farther, it had a higher altitude, and it flew for a longer amount of time. So, no matter what, it demonstrated a farther range than the previous test. And if we make the assumption that this is the same missile [which has yet to be confirmed], then we would say that [the North Koreans] were probably trying to test the missile at a greater capacity, if not its greatest capacity.

With these new numbers, it’s crunching out to look like between a 10,000- and an 11,000-kilometer [missile]. If it’s as far as 11,000, that puts every U.S. state but Florida in range. That includes Washington, D.C. [and] New York City.

Friedman: In January, after Kim Jong Un announced around New Year’s that North Korea was in the final stages of being able to test an ICBM, Donald Trump went on Twitter and said, in response to the idea of them getting one that is nuclear-tipped, “that won’t happen.” Later on H.R. McMaster, Trump’s national-security adviser, said that it is unacceptable for North Korea to be able to threaten the United States with nuclear weapons. Given what we know so far about this latest ICBM test, where are we on the trajectory toward that red line by the Trump administration? What we saw today did not involve nuclear weapons. So how would you assess where we are on the question of an ICBM that can reach the United States and carry nuclear weapons?

Hanham: That moment has come and gone already. When Trump made the tweet I actually wrote a blog post laying out why they were already nearly there. July 4 they proved it. Today they proved it again.

Verifying that they have a nuclear warhead is more difficult. [The North Koreans] published photographs of Kim Jong Un standing beside this large, silver orb shape. We don’t have X-ray vision, so we can’t tell what’s inside of that orb. There are attributes of that orb that make it seem plausible it could be a warhead. We also measured it, and it definitely fits into a number of their missiles, including the Hwasong-14. We can’t definitively prove that it’s a warhead.

But after five nuclear tests [by North Korea], it’s not implausible that they would have made a compact warhead. And from a policy standpoint, I would prefer to err on the side of caution [in assuming North Korea has the capability to launch a nuclear-tipped ICBM], not just because I think we’ve been too naive about North Korea for too long, but also because I don’t want them to [feel the need to demonstrate that capability by testing] a live nuclear warhead in an atmospheric test on the tip of a missile. Other countries have done that before, like China in 1966, but China’s got a lot more landmass than North Korea does, and there’s no safe direction for North Korea to conduct that kind of atmospheric nuclear test on a tip of missile—there’s no way for people to discriminate between it being a missile test and a full launch of war.

North Korea seems to be pretty sensitive to [U.S. officials] constantly goading them that they can’t do this, or they’re too backwards, and that’s why they’re publishing all the technical details of their missiles and that’s why they’re showing us all these photographs.

Friedman: Is there a big difference between being able to successfully test-fire an ICBM and being able to put a nuclear warhead on that ICBM that can survive reentry into the earth’s atmosphere? Is there something to suggest that North Korea is still far away from that particular goal, even if they have a nuclear warhead and have successfully tested nuclear weapons?

Hanham: You’re probably going to find an expert somewhere who will say yes. I’m not that expert. China used oak as a medium for its reentry vehicle. Like, the wood. [The North Koreans have] done the hard parts already. I mean, if they miss New York and hit New Jersey instead, that’s still really bad.

Friedman: So basically, based on what we know now, do you agree with the statement that North Korea has the capability to hit the United States with a nuclear weapon?

Hanham: The scientist in me says probably. But the policymaker in me says it doesn’t matter. We need to move ahead as though they do, because the consequences of being caught surprised are worse.