Staying Sane with Cuckoo and Code Generation

Please note that this post won’t go over the basics of Cuckoo, as the README provides a great introduction to the library.

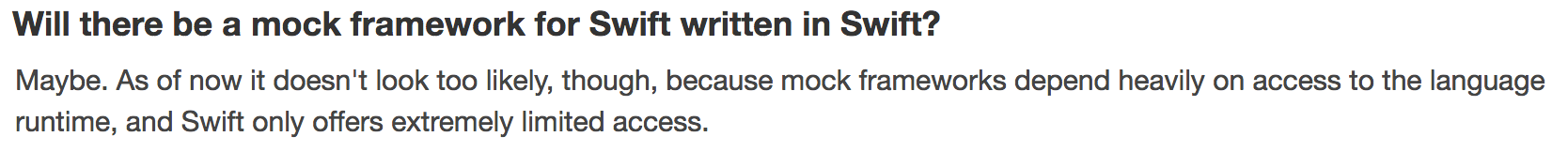

Do you write unit tests? You should. Writing mocks for my tests seemed to be a lot easier in Objective-C. OCMock makes great use of Objective-C’s dynamic nature and it makes mocking a breeze. However, the OCMock website has this to say:

Disappointing. Accurate.

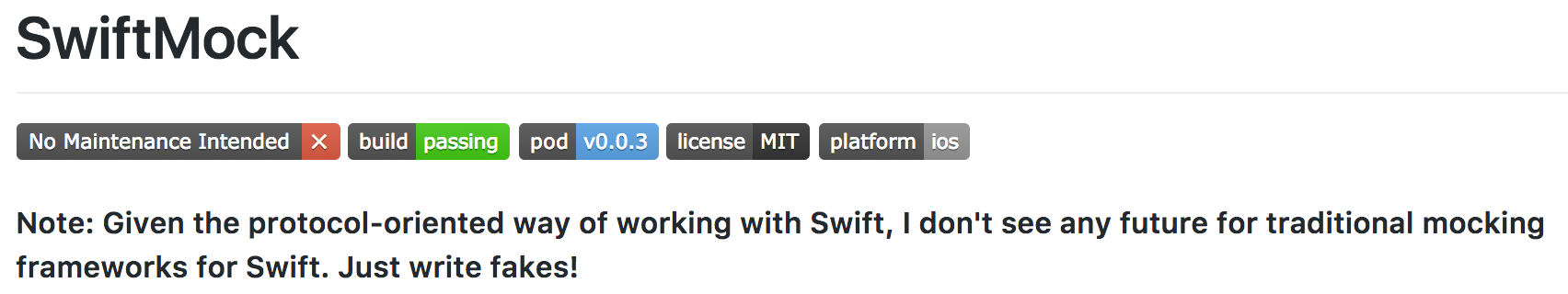

Alright, off to find an alternative. The best that I could find was SwiftMock, but that came with an even sharper let-down:

It seems that Swift’s lack of reflection means that we’ll be doomed to doing things manually and rewriting the same type of code, again and again.

So, I resorted to rolling my own mocks. It’s not that bad. Really. I built a little mocking framework of my own based off of a Mock protocol and use of Swift’s basic reflection, and all was happy in the world of TDD.

When you’re writing a lot of code and all of the tests that should come with it, all of the time spent writing boilerplate for your mocks gets tiring. I was hungry for something more efficient.

Then, I was introduced to Cuckoo.

Cuckoo is a mocking framework for Swift that uses code generation to create the boilerplate that you’d otherwise be writing yourself. It comes with a lot of functionality that I think would be far too tedious and repetitive to do on your own. It also ensures consistency, which is something that I’ve found to be sorely lacking in the world of hand-rolled mocks.

Code Generation versus Reflection

Most programming languages use reflection to dynamically perform things that we would otherwise have to write repetitive boilerplate for. OCMock uses reflection to create mock objects. It doesn’t actually create a new class for each type you wish to mock. Reflection allows languages like Objective-C to dynamically create mocks, check for equatability, and perform JSON serialization.

As of yet, this isn’t an easy feat in Swift. The Swift language shuns dynamic behaviour and encourages safer methods. Code generation, on the other hand, fits very well with Swift’s type safety. You have code that can be read by a human and verified by a compiler.

It felt weird to me at first. I may not have written the boilerplate, but it’s still there. Written by a tool and hidden in the background. But this seems to be the way forward in a language like Swift. Frameworks like Sourcery and SwiftGen let you adopt code generation for these tasks that might otherwise be done via reflection.

The lack of reflection and strong type safety mean that code generation is the new go-to when it comes to reducing your time spent on monotonous tasks and more time working on the important parts of your app.

Cuckoo’s use of code generation has numerous benefits over the reflection approach, such as type checking, optimization, and the ability to step through and debug the generated code.

Using Cuckoo without going nuts

Cuckoo has become easier to use with a fair bit of trial and error. Here are some insights that I’ve learned so far.

Get comfortable with ParameterMatchers

Looking at this example:

stub(mock) { stub in

when(stub.greetWithMessage("Hello world")).thenDoNothing()

}

We’re stubbing the behaviour of calls to the greetWithMessage function when passed the string “Hello World”. It’s important to note here that the code doesn’t actually expect a String object. It expects a Matchable.

The Matchable protocol is used to verify that an argument matches a set of criteria. The reason we can pass the “Hello World” string to the example above is because Cuckoo kindly extends String to conform to Matchable out of the box:

extension String: Matchable {

public var matcher: ParameterMatcher<String> {

return equal(to: self)

}

}

This means that any mocked function expecting a String Matchable can be passed an instance of String.

How can we match on our own custom objects?

Say we have a logInWithCredentials function that takes a UserCredentials object as an argument. When Cuckoo generates mocks, we’ll need to pass a Matchables object to the loginWithCredentials function. We can extend the UserCredentials object just like String was extended:

extension UserCredentials: Matchable {

public var matcher: ParameterMatcher<UserCredentials> {

return ParameterMatcher { $0 == self }

}

}

And now we can stub the function like so:

let testCredentials = UserCredentials(name: "Bradley", password: "pass")

stub(mock) { stub in

when(stub.logInWithCredentials(testCredentials)).thenDoNothing()

}

Remember that you can also do more complex checks than just comparing equality.

let matchesUserStartingWithB = ParameterMatcher<UserCredentials> {

$0.name.first! == "B"

}

stub(mock) { stub in

when(stub.logInWithCredentials(matchesUserStartingWithB)).thenDoNothing()

}

Run the script before compiling your tests

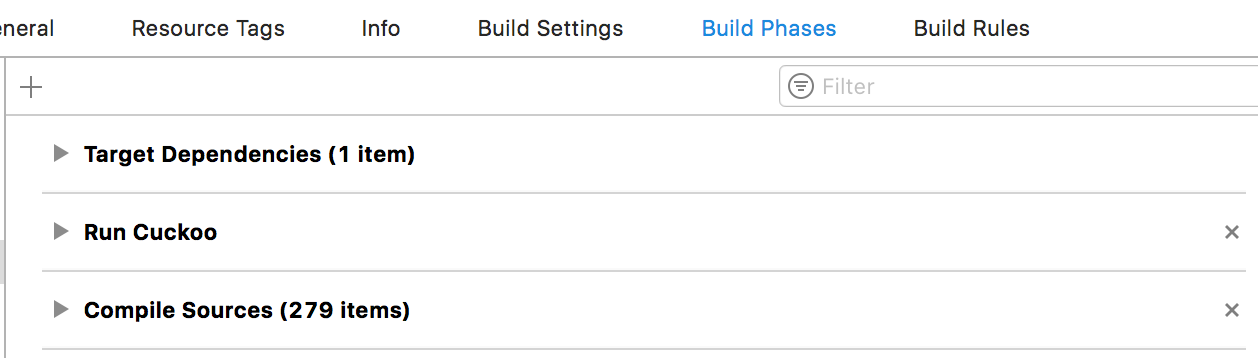

Cuckoo’s documentation suggests that you add a Run Script phase to your test target for the generation of the GeneratedMocks.swift file that contains your mocks.

You can save yourself some time by avoiding my stupid mistake: Make sure that the Run Script phase for Cuckoo is placed before actually compiling your tests.

Break down unclear compilation errors

Cuckoo can throw some rather cryptic compilation errors when things aren’t right. Cuckoo has also been known to break the Swift compiler at times and give it a segmentation fault, in which case you won’t get the helpful red text on the line that is causing the breakage. Make sure to look carefully at any compiler errors and read the messages to pinpoint your problem.

Standard debugging techniques apply: break the issue down into its simplest parts. Eliminate all possibilities until you know what the issue is. Simplify what you’re trying to do until you get it to work, and build it up from there.

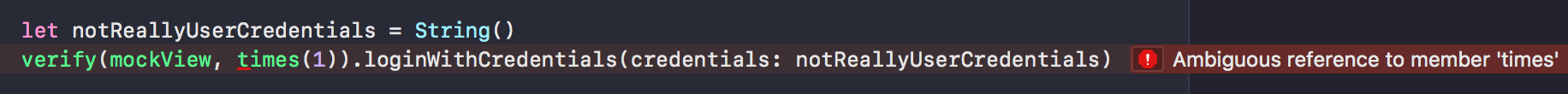

If you mismatch types, the errors can be particularly bad:

What’s happened here is that the loginWithCredentials method is expecting a Matchable for a UserCredentials object, but instead, I’ve passed it a String.

In situations like these, or when you have complex expressions and suspect that it might be impacting the compiler, it helps to strip away the type inference until things start working again. So rather than:

stub(mock) { stub in

when(stub.logInWithCredentials(ParameterMatcher { $0.userId == 123 })).then { response in

print(response.statusCode)

}

}

I’d be more explicit in specifying the types, like so:

let matchesUser123 = ParameterMatcher<LoginCredentials> { $0.userId == 123 }

stub(mock) { stub in

when(stub.logInWithCredentials(matchesUser123).then { (response: LoginResponse) in

print(response.statusCode)

}

}

Call verify last, not first

Here comes the facepalm moment.

Coming from an OCMock background, you may be used to calling OCMExpect before actually calling your production code:

- (void)testLoggingInCallsLoginService {

OCMExpect([mockLoginService loginWithCredentials:OCMOCK_ANY]);

[classUnderTest startLoginProcess];

}

Do this with Cuckoo and your tests will always fail. Calls to verify are checked when you call it, so call it after calling your other code, not before.

func testLoggingInCallsLoginService {

classUnderTest.startLoginProcess()

verify(mockLoginService).loginWithCredentials(any())

}

If you can’t beat them, exclude them

Structs can’t be mocked due to the fact that they can’t be inherited from (you’d stub a protocol instead). Some classes can be tricky as well, such as complex subclasses of UIViewController. Sometimes, I have a protocol in a file that I want Cuckoo to generate mocks for, and another object in that same file that I want Cuckoo to ignore. You can do this quite easily with the --exclude option:

${PODS_ROOT}/Cuckoo/run generate --testable "$PROJECT_NAME" \

--exclude "ThatStructIWantToExclude,\

ThatOtherObjectThatBreaksMyBuild" \

--output "${OUTPUT_FILE}" \

"$INPUT_DIR/FileName1.swift" \

"$INPUT_DIR/FileName2.swift"

The --exclude option is a relatively new addition that solved quite a few problems that would otherwise cause a need to revert to hand-rolled mocks. Let that be a good lesson to read the documentation frequently.

Use it when it makes sense

Cuckoo is a time saver. Spend a bit of time up front to learn its ins and outs, and you may find it to be the most efficient tool for the job. If it isn’t, don’t use it.

There are scenarios where a quick hand-rolled mock is the best way to go, and I still do it when it’s the quicker option. Be pragmatic and do what works for you and your team.

Write valuable software. Test your code. Have fun. And happy Swifting!

Comments