Most fine art genres have defining aesthetic characteristics that identify themselves as such -- Realism is realistic, Cubism has cubes, Pop art pops. Even those that aren't quite so clear -- Surrealism, Impressionism, Modernism, Op Art -- can be explained with a specific intention, influence, era or methodology.

And then there is folk art. The umbrella term applies as much to a textile made in 17th century Africa as a DIY ceramic piece for sale on Etsy. The dominant identifying factor of folk art is probably its distance from the academic mainstream. However, other (similarly murky) categories such as self-taught art and outsider art share such a classification too. The description of "not academic" certainly fails to describe and encompass the wide and wild range of folk art possibilities.

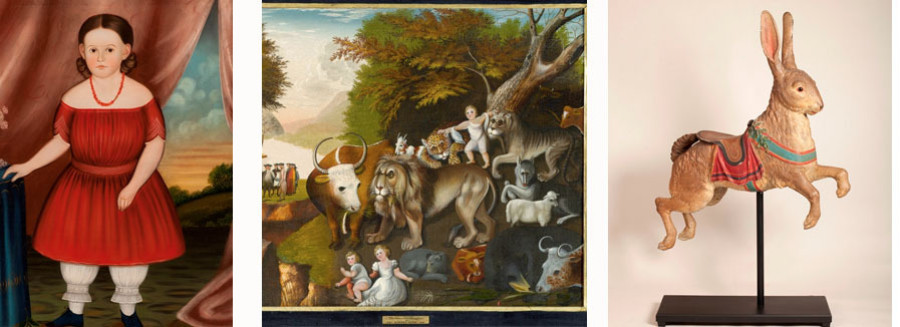

To settle this dilemma, we reached out to Stephanie Knappe and Catherine Futter, both curators at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. The two curated the current exhibition,was "A Shared Legacy: Folk Art in America," a show culled from the collection of Barbara L. Gordon. We asked the curators to elaborate on the still nebulous artistic genre.

Unidentified artist. Still Life with Basket of Fruit, 1830–50. Oil on canvas. 24 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. Courtesy of the Barbara L. Gordon Collection.

"It might not be the answer you're looking for, but it's the answer we've been giving ever since we started the project," Knappe said. "Folk art really is something that's in the eye of the beholder, or in Barbara Gordon's case, the eye or the heart of the collector."

Barbara Gordon is a collector who lives outside of Washington, D.C. She accumulated her art collection over the course of 25 years. The process started with shopping at flea markets and estate sales. Eventually, Gordon sold her first lot of works and started over from scratch, this time with an additional dose of discipline, determined to hone a truly cohesive, refined and museum-worthy collection.

"For Barbara Gordon's collection," Futter added, "almost everything she has is based in either tradition or community. So that separates folk art from outsider art. Outsider art tends to be not necessarily part of community, not necessarily part of tradition."

Both curators emphasized that "Shared Legacy" presents Gordon's vision of what folk art is, and is not necessarily representative of a general consensus. "There are no quilts, no coverlets, no textiles of any kind," said Futter. "There are things that might not fit anyone else's definition of folk art, because they are made by artisans who received training. You can see this is a very personal collection for her, based on the things that fall just a little bit outside the definition."

Attributed to John Scholl (1827–1916). The Wedding of the Turtle Doves, 1907–15. White pine, wire and paint. 37 x 24 x 17 in. Courtesy of the Barbara L. Gordon Collection.

We've previously spoken about American folk art with Paul D’Ambrosio, curator at the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts, on an exhibition titled "Folk Art, Lovingly Collected." In this conversation, D'Ambrosio identified some of the unifying factors driving 18th- and 19th-century American folk art as the rise of the middle class as well as advancements in industrial technology.

"They didn't have an industrial technique but they had an understanding of mass production and that's an idea that came along with the industrial revolution," he explained. "In 1800, artists imitated the mechanical means with their hands' work."

Knappe and Futter agreed with the sentiment behind D’Ambrosio's reading, and expanded it. "Many of the artworks come from before the rise of the middle class, before the rise of mechanization," said Knappe. "It really is about carrying on and carrying through tradition during a time of great change. There is a stability to be found in traditions and keeping the past alive."

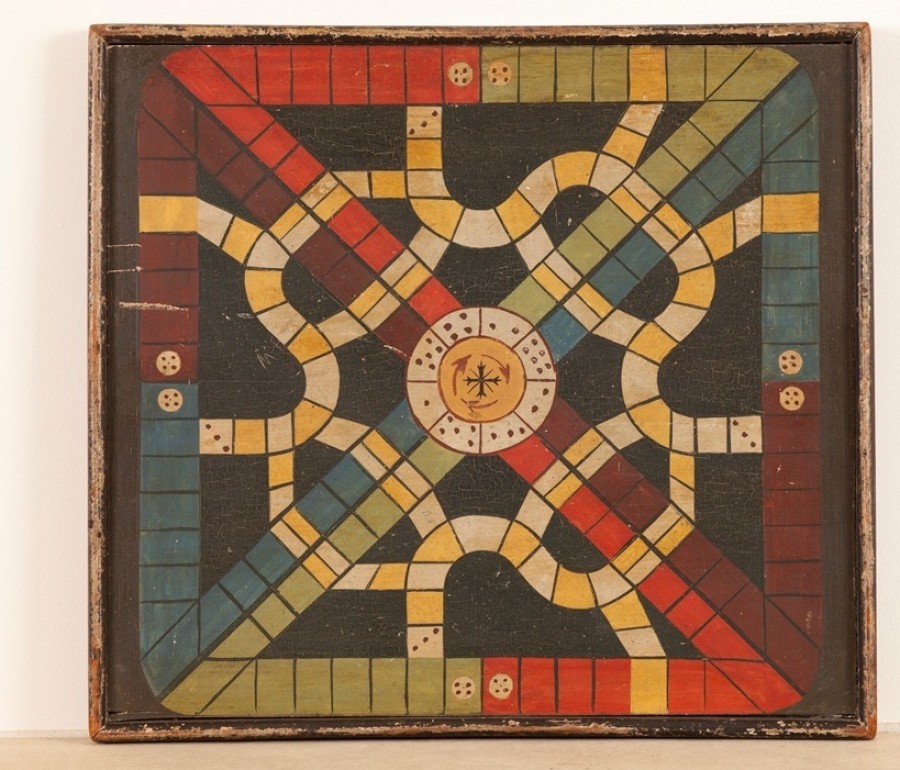

The works on view in "A Shared Legacy" show just how many forms such a yearning for stability can take. John Scholl's "The Wedding of the Turtle Doves" is a white pine and wire sculpture, a bizarre totem that's at once elegant and kitsch. Then there's an anonymous board game made around 1880, whose bright colors and winding shapes resemble some sort of abstract mandala.

Unidentified artist. Gameboard, ca. 1880–1900. Wood, paint and iron. 18 ½ x 16 ¾ x 1 ½ in. Courtesy of the Barbara L. Gordon Collection.

"These were artists who were aware of themselves as artists, as makers and creators," said Knappe. "They were aware of their talent, I believe."

"But I don't think they were thinking about being in museums," Futter clarified. "Firstly because museums came later than many of these artists. And also, a lot of these were functional objects -- the chests of drawers, even the paintings had functions in conveying information, they had political messages and social messages. They weren't seen as museum objects but they did see themselves as participating in entertainment."

But the objects had a value outside of their utility, Knappe asserts. She points out a trio of Lamb family portraits. "We know Mr. and Mrs. Lamb had daguerrotypes made prior to the making of this portrait so there is something in the decision to sit for a portraitist that shows the value of the painted portrait beyond capturing a likeness," she said. "These were all are very conscious decisions."

Attributed to Joseph H. Davis (1811-1865). Dr. Nathaniel Grant Family, 1835-36. Watercolor and graphite on wove paper. 15 ½ x 22 ¼ in. Courtesy of the Barbara L. Gordon Collection.

As you can see, folk art is a difficult genre to pin down. This particular exhibition is made all the cloudier due to the fact that around half of the artists on view remain unidentified. "We know the makers of the carousel figures but we don't know who carved them," said Futter. "Or, we don't know who made some of the painted chests but you can identify which communities they came from."

Both curators admitted they were surprised by the high number of unidentified artists on the roster.

In 2013, Roberta Smith submitted a modest proposal of her own, challenging the art world establishment to loosen up its rigid boundaries separating folk art from the domain of so-called serious art. "Why don’t you, as Diana Vreeland might have asked, mix folk art in with the more realistic, academically correct kind that has so dominated museums since the 19th century?" She implored curators and academics to bid farewell to the nebulous folk-academic division once and for all.

Although this clearly hasn't happened in full, Knappe and Futter said the process for appraising folk art is not all that different from the valuation of any fine artwork. "I would say most art is held to the same standards in terms of: Do you know who made it? Do you know where it was made? Do you know when it was made? Do you know the condition? Who owned it?" explained Futter.

Knappe added: "And then those undefinable qualities that elevate art above and beyond." It seems, beyond all the jargon, the appeal of folk art and fine art both stem back to similar ineffable features -- originality, vitality, virtuosity, to name a few. "There is this re-interest in folk art and putting it in the context of academically trained artists, and seeing that those things aren't so disparate, and that they can live harmoniously together," Futter said.

Daniel McDowell (1809–1880). Still Life with Watermelon, 1860–80. Oil on canvas. 20 ½ x 27 ¾ in. Courtesy of the Barbara L. Gordon Collection.

If a folk art exhibition, rare as they may be, isn't currently showing in your vicinity, a trip to the local flea market or even Etsy can do the trick. The recent resurgence of the DIY movement -- and, yes, the Internet's most creative online marketplace -- has allowed for spaces where contemporary folk art lives and thrives.

Folk art was part of the Nelson-Atkins Museum's original collection when it opened in 1933. Thus, it seemed a natural move for Knappe and Futter to bring the Kansas City museum back to its roots, at a time when folk art is gaining momentum around the world. Not to mention, the unpretentious, locally grown spirit of folk art bodes well for a museum located outside the oft listed art destinations of the world, or even the United States.

"We want to communicate that places that are not major urban centers or centers of creativity, that were based in traditions, can continue," explained Futter. "Those still are vibrant. You can look at these different folk art forms and see how they relate to academically trained artists, but they also have a connection on a more human scale, that's part of our experience. When we go and look at the Mona Lisa, for instance, how much can we really relate to her? I think that awakening of 'Oh! This is art too!' is part of what we wanted to do."

"And expanding the breadth of creative expression," Knappe added. "We have these really important and engaging moments happening not just in the art academies, not just in the big cities. Expanding the definition of what art is and what art is worth attention."

Related

Before You Go