Wot I Think: Endless, Nameless

Restoration Comedy

I'm so glad I don't review books for a living. When discussing a game, you have to be careful to avoid both narrative and mechanical spoilers as best you can, but generally there's a great deal to talk about around these. But I'm not sure the editors of the Times Literary Supplement would take kindly to my describing how easy it is to turn a book's pages, as I desperately find ways to avoid ruining the story for anyone who might want to read it. I often feel in a similar situation when reviewing adventure games, and never more so than when talking about interactive fiction. Yes, there are mechanics to discuss, of course. But really, with text on a screen, it's tougher. And when that game has a crucial twist in the opening hour, er, you're screwed. So it's with this in mind that I suggest you go play Adam Cadre's Endless, Nameless before you read beyond the point I'll clearly mark below. I'll not ruin the entire game, of course. But, well, play it first.

Um.

Look, the game's brilliant. Go play it. It's free, for goodness sakes - what have you got to lose. Would you like a score to convince you? I give it 50 fountain pens out of a typewriter. You don't need to know anything, because you're not meant to know anything.

Okay, you want traditional? I'll describe the opening moments so you can say, "Oh, I recognise these opening moments," when you play it.

Things begin emulating a text interface computer from the late 80s. The game, you're told, is from a bulletin board, originally known as the Endless Quest, now updated to be the Nameless Quest. That's significant. And in keeping with the era it purports to be from, it's often a fiddly pain. Confirming to those pernickity ways of the classic Infocom adventures, you have to be very precise in your instructions, withdrawing items from pockets before using them, for instance. To match the old-school typing, it's set in an old-school world: classic RPG text adventure land, with taverns, village squares, grumpy trolls, and a dragon to kill. Indeed, you, you're told, are the chosen one. You! You're special. You are. Then things get weird. Play the damned game.

So you've played it, and I'm not needlessly ruining it for you when I talk about the other world. The in-between world, a world that acknowledges the present day both in terms of not being a fantasy setting, and a more modern, intuitive IF behaviour. Because you died trying to do something, and had a meta-awakening in a house packed with thousands of clones of you - whoever "you" actually may be. And you realise that each of these iterations of you is a failed attempt to complete the quest, all accepting their new life in a pleasant if crowded home, where Rocky IV plays endlessly on the TV, and a dining room is packed with food. Sure, outside there's a beach filled with thousands of trolls, killed by the thousands of yous that have passed through the game. And certainly there doesn't appear to be any escape, nor any possibility of violence to make things more interesting. It's a limbo, an existential crisis of interactive fictioning. But there's a way out. Sort of.

And then the real nature of the game becomes apparent, the hook I'd love to have sold it with above were it not such a shame to reveal. All those past yous, lots of them became experts at various aspects of the game. They got further than you did before they died, and as such can give you tips. And when you find how to get back into the other world, you can start to apply this knowledge and see how much further you can get before you find your life taken away once more. And repeat.

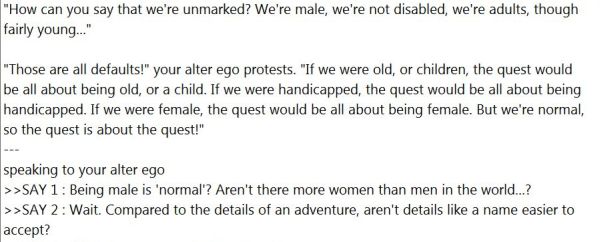

It gives you one heck of a reason to learn about your IF interpretor's Record function. It proves incredibly useful to record text entries for the portion of the game you're sure about, and then keep adding those as you know more and more what to do. It saves lots of unnecessary repetition. But rather brilliantly, even if you're just saving and restoring, the advice of the alter-egos still seems to know what you've done, and responds accordingly. Which to me strikes as witchcraft.

Beyond the superb, brain-aching premise, and a fantastically interesting way to explore the foibles of classic adventures, it's also superbly written. As you'd expect from Adam Cadre, multiple Xyzzy award winner. Not only are the descriptions perfectly crafted, but the display of cracks in the reality, the moments of confusion, the glimpses behind the curtain, are all incredibly well delivered. It manages to not only faithfully be the thing it intends to dissect, reinterpret, and even gently spoof, but also be something other, something outside of it and looking in.

I was at first daunted by the prospect of having to get so many fiddly, fickle details correct, and often in the right order, the first time I realised I was going back in. But drawing breath and just doing it, it instantly engrossed. I'm sat here with pages of notes of spells in front of me, graph paper for mapping, and the knowledge that I've still an awful lot to work out before I can successfully finish this one. And as with the best of IF, I've also got vivid mental images of everywhere I've been, everyone I've spoken to, and the dragon I so wish I could kill. Except for one person. I've no mental image of the character I'm playing. And, this game's made me realise, nor have I ever. Which is very much the point.

You can read Cara Ellison's interview with Adam Cadre, amongst other IF luminaries, in her extraordinary choose your own interview.