Hurricanes, earthquakes, and nuclear war, oh my. And don’t forget to add a near-record wildfire season to that list of disasters. According to the National Wildfire Coordinating Group, there are 137 large wildfires currently raging across the American West, burning a total of 7.8 million acres. That’s not yet as bad as 2015, which saw 8.4 million acres burned, but it’s only September and this is already the third worst year for wildfires in the last decade. It’s already way ahead of the previous 10-year annual average of 5.4 million acres burned.

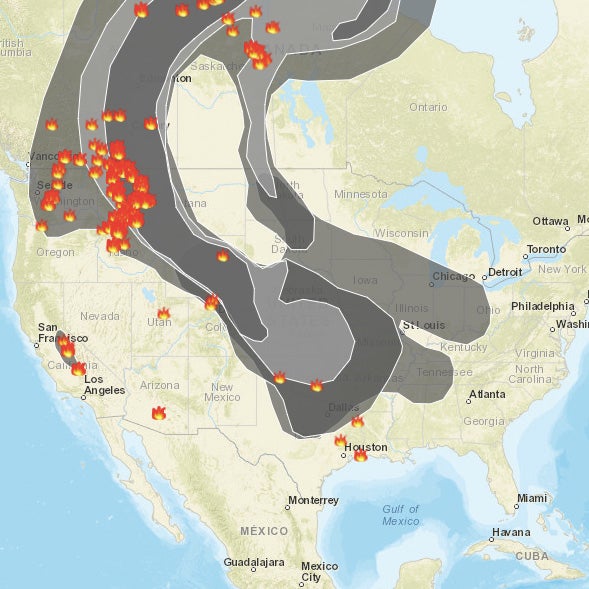

You’ve seen the apocalyptic images from the Columbia River Gorge, Glacier National Park, and the Los Angeles Suburbs, but those fires are only a small part of the overall picture. Currently there are 13 active wildfires in Washington, 26 in Oregon, 23 in Idaho, 46 in Montana, and 38 in California. I could go on, but you get the idea. (You can find all the data on current fire conditions here.) Smoke from these fires currently envelopes an area stretching north to the Queen Maude Gulf, in the Canadian Arctic, west to Seattle, south to Waco, Texas, and east to Columbus, Ohio.

Why is this happening?

Extreme Heat

This year has also brought record heat to the West. Just last week, San Francisco recorded its highest temperature ever—106 degrees, three more than the city has ever seen before. It’s been the hottest, driest summer in Seattle—ever. It’s the hottest, driest summer Montana has ever had. When I drove past the La Tuna fire, the largest in Los Angeles’s history, the external temperature gauge in my Land Rover registered 114 degrees.

High temperatures bake out the moisture absorbed by forests during the extremely wet winter. Because heat leads to drier fuel, the relationship between each additional degree of temperature and the likelihood and severity of fire has been found to be exponential: every additional degree of temperature is more likely to lead to fire than the last.

The Drought Persists Despite a Wet Winter

While the historic drought that afflicted the West over the last five years officially ended this winter, its effects are still being felt. In the Sierra Nevada mountains alone, the drought claimed an estimated 26 million trees. Statewide, 102 million have been killed. Most of those have not been cleared, and their dried out husks clutter forest floors, and still stand on mountain sides, creating perfect fuel for wildfires. Forests that once had open ground under the trees are now so cluttered with dead logs that it’s become impossible to walk off-trail across much of the western Sierra.

All this winter’s rain also led to huge growth for grasses and underbrush, which this summer’s record heat then dried out, turning it into massive amounts of tinder. Stack dry grass under a dead log, and you have the perfect recipe for a campfire. Scale that across the entire west and you have our ongoing disaster.

Fire Management Meets Urban Planning and Politics

According to an analysis by the insurance industry, 60 percent of new homes constructed since 1990 are located in what’s known as the Wildland-Urban Interface Area. In short, we’re building our homes in areas that naturally burn. More than $500 billion of homes exist across the 13 western states in areas categorized as at extreme or high risk of wildfires. And that construction is making it more difficult to proactively head off massive fires in those areas with controlled burns.

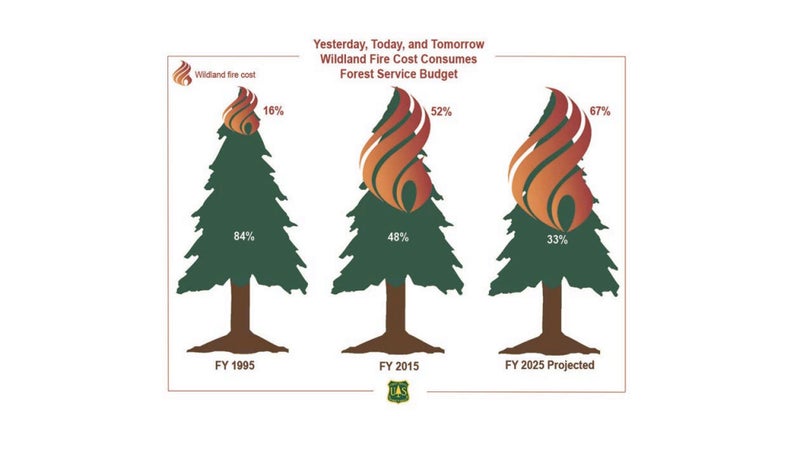

The other big factor limiting wildfire prevention right now is budget. All these huge fires cost tons of money to fight, and that money is coming out of prevention budgets. Every time a state or the Forest Service has to fight a fire, its financial ability to prevent other fires diminishes.

“As more and more of the agency’s resources are spent each year to provide the firefighters, aircraft, and other assets necessary to protect lives, property, and natural resources from catastrophic wildfires, fewer and fewer funds and resources are available to support other agency work—including the very programs and restoration projects that reduce the fire threat,” reads the U.S. Forest Service’s 2015 budget report. Fifty-two percent of its money went to firefighting that year—a percentage that’s expected to grow to 67 percent by 2025. This year alone, the Forest Service is already $300 million over budget for fire fighting.

The Forest Service knows it needs to change the way it deals with fire, but it’s so busy trying to fight fires, and going so broke fighting them, that it can’t afford to.

It’s All Connected to Climate Change

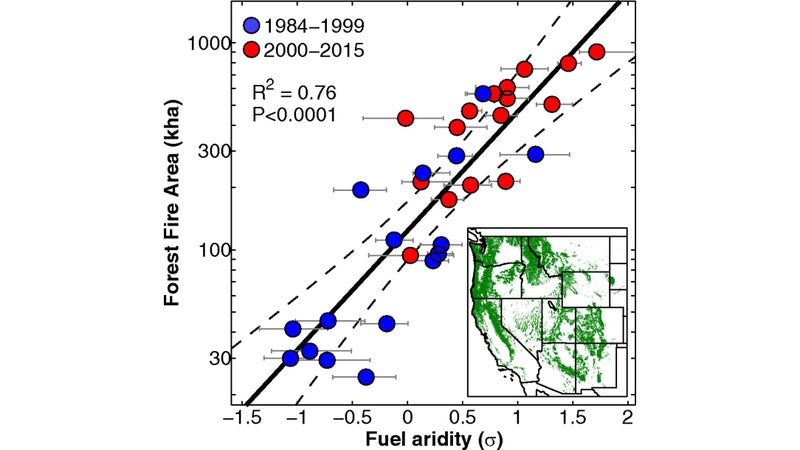

Since 1970, the annual wildfire season has grown in duration by 78 days. Since 1984, the area annual burned by wildfire has doubled. The Forest Service estimates that area may double again by 2050.

Climate change is also bringing wildfires to new areas, and to a degree never before seen. Since the 1980s, the area burned annually in the northern Rockies has increased 3,000 percent. In the Pacific Northwest, it’s a 5,000 percent increase over the same period. Between 1978 and 1982, the average burn time of a fire was just six days. Between 2003 and 2012, it was 52 days.

“Warmer temperatures and earlier snowmelt have contributed to drier conditions,” reads the research behind those figures. “But cooler, more moist forests, such as those in the northern Rockies, have seen the greatest drying due to changes in the timing of spring, and the greatest changes in forest wildfire.”

“Observed warming and drying have significantly increased fire-season fuel aridity, fostering a more favorable fire environment across forested systems,” reads another study. “Human-caused climate change caused over half of the documented increases in fuel aridity since the 1970s and doubled the cumulative forest-fire area since 1984.”

How Do We Pay for This?

By the end of the century, the West is projected to warm by an additional 3.5 degrees Celsius. Given the exponential relationship between temperature and wildfire, that’s bad news.

The Forest Service elaborates:

“Changing climatic conditions across regions of the United States are driving increased temperatures—particularly in regions where fire has not been historically prominent. This change is causing variations and unpredictability in precipitation and is amplifying the effects and costs of wildfire. Related impacts are likely to continue to emerge in several key areas: limited water availability for fire suppression, accumulation at unprecedented levels of vegetative fuels that enable and sustain fires, changes in vegetation community composition that make them more fire prone, and an extension of the fire season to as many as 300 days in many parts of the country. These factors result in fires that increasingly exhibit extreme behavior and are more costly to manage. The six worst fire seasons since 1960 have all occurred since 2000. Moreover, since 2000, many western states have experienced the largest wildfires in their state’s history.”

To pay for part of this season’s suppression budget, $300 million for the Forest Service has been written into the Hurricane Harvey relief bill. But the agency is desperately in need of a major new source of funding. If it doesn’t get one, it’s estimated that the budget for other activities, like fire prevention, could shrink by $700 million annually between now and 2025.

This is not a problem we can afford to neglect. The solution to this funding shortfall is obvious—fires need to be treated like the disasters they are, and fighting them needs to be paid for in the same way we deal with other natural disasters, like hurricanes and earthquakes.

“Congress needs to step up and treat these infernos like the natural disasters they are,” says Senator Ron Wyden (D-Oregon), who introduced the Wildfire Disaster Funding Act to congress in 2013. The bill, which has since languished in committee, creates a federal fund dedicated to fire suppression, supplanting budgets drawn from states and the Forest Service’s general budget.

Now, state lawmakers are calling on Congress to revisit the bill. “Congress needs to act,” Oregon Senate President Peter Courtney wrote in a letter to Congress last Friday. “This is no time for politics. It’s time for action. My state is on fire.”