The Other Sister

Ellie was seven when she asked for a rat. We were strapped into our bucket seats in the minivan as our mother ferried us somewhere that is now lost to history. “Not while I’m alive,” my mom said over her shoulder, cranking the wheel as she turned down another street.

My sister sat quietly for a few seconds, absorbing the rebuff. Then she turned to me and smiled, two buckteeth pushing over her bottom lip.

“Ciara,” she said. “When mom dies, we get a rat.”

She settled back, content, just as she did several years later, after she asked if she could be the flower girl if I got married. When our mom explained that flower girls were usually young children, Ellie said she would be a flower woman instead.

Now 26, the thick curtain of bangs cut above her eyebrows has grown. Several years of braces corralled her front teeth. She finally learned it wasn’t her pinky she should thrust in the air if she wanted to give someone the finger. But she still wants to play like we did when we were younger.

“I’m not a kid anymore,” my mom told Ellie recently as she explained why she didn’t want to join her in a game we enjoyed in elementary school. Ellie and I would crawl on the carpet pretending to be dogs while our mom faithfully fed us invisible bowls of food and scratched our heads. She had retired from the role when Ellie last asked to play. By then, Ellie wasn’t a kid either.

“But I still am,” she said. “Why am I?”

Eight years ago, after Ellie—not her real name—turned 18, becoming an adult in the eyes of the law, a piece of paper was filed at a King County Courthouse formalizing a decision that was reached without much discussion, drama, or fanfare. If my mother died, one of her sisters would become Ellie’s guardian until I turned 30, at which point I would take over.

Ellie still sleeps in her childhood bedroom and our mom still drives her around Bellevue, where we grew up. She schedules Ellie’s doctor appointments and manages her money. She trims her toenails. Ellie doesn’t want a rat anymore but when our mom dies, she’ll get me.

I turned 30 this summer.

Ellie, like millions of people in the United States, has autism. And while there are no official estimates, specialists suggest there are millions of siblings of Americans on the spectrum too. For aging parents, worried about their children’s fate when they can’t look out for them anymore, those siblings are a second generation of caregivers already in the family.

The longest relationships people with disabilities will likely have is with their brothers or sisters. But research, services, and support are focused on the person with disabilities and their parents, says Katie Arnold, director of community education at the Institute on Disability and Human Development at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “Siblings of people with disabilities are often overlooked,” she says, “and sometimes even totally forgotten in the mix.”

The Arc, a national organization that advocates for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, estimates that as many as 700,000 adults with a disability like autism live with parents or another family member aged 60 and older, with no plan in place for when they’re no longer able to provide support.

As Americans with disabilities live longer, often in their family home, Robin Shaffert, who works in individual and family support at the Arc, says it’s a bigger problem than ever before, compounded by a shortage of affordable, appropriate housing virtually everywhere in the country, and low wages for professional caregivers. “Many of these situations,” she says, “are very urgent.”

In Washington, the State Department of Health estimates 8,000 to 12,000 children have some form of autism. And most individuals with the disorder continue to require significant help into adulthood.

Photographs courtesy Ciara O'Rourke

The reality of our mother actually dying finally resonated with Ellie when we lost our grandmother about five years ago. She was at Nana’s house when she called our land line shrieking that Nana was lying unconscious on the ground. When my mother and I arrived, Ellie was sobbing. She paced and repeated the same words through choked tears as we huddled in the backyard with the rest of the family. Nana’s dead. Nana’s dead. Nana’s dead.

It was the first death of someone she was close to; it wasn’t long before she started to fret about our mother.

“Wait,” she said one day. “You’re old. When are you going to die? Who is going to take care of me when you do?”

I had moved to Austin, Texas, by then, but I was also waiting in the wings. For several years I anticipated becoming my sister’s guardian. I just didn’t know what it would look like in practice.

Ellie’s concerns inspired my mom to email me a primer detailing how much money Ellie gets from Social Security and which dentist she sees. Ellie qualifies for reduced bus fare on Metro, she wrote, and for the Access bus, which provides curb-to-curb service for passengers with special needs.

But Ellie started to prep me on her own, looping me in on her daily routines.

“I am on the Access bus now I just want to start updating you for when you are my guardian,” she texted me one evening in late 2013.

Then she texted my mother. “I told Ciara I am on my way,” she wrote. “I’m training her.” When I didn’t respond to Ellie’s text, she messaged my mother again. “Can you train her more properly before you pass away that you say OK thanx when I tell you I’m on Access or arrived somewhere...I want her to know the routine for when the time comes.”

For me, the prospect can feel paralyzing. I imagine myself searching for the email my mom sent or calling the disability attorney she sometimes consults. But what if the lawyer’s dead too? If I’m living out of state, will I have to move back or fly Ellie to me? Could she get a new job, new social services, and new friends if she did? Will I even have a job that can support both of us?

“No, no, MoMo!” Catherine Brewer leapt up as her sister, Morgan, walked into the kitchen with a cup of water sloshing at the brim.

“Mom!” the 14-year-old called, carefully taking the cup from Morgan’s hand before it spilled. Morgan, 16, had recently started dumping water off the deck, but empty handed, she charged outside into the August heat anyway, making a low humming noise. Her headphones were on and she didn’t look back at Catherine, who again pulled her knees to her chest in the breakfast nook where she was sitting. Catherine had been telling me how weird it was that she used to be jealous of friends who would complain that their older sisters were annoying. She was about eight when she felt that pang, a yearning for the kind of sibling relationship you might see on TV, a younger sister sneaking into her older sister’s room, the older sister kicking her out and slamming the door in a huff.

“Why can’t you yell at me?” Catherine imagined saying to Morgan. “Why can’t you tell me to get lost so you can have private time?” But Morgan can’t say much. Her speech is limited, and when she yells she’s not mad. She’s just expressing an emotion she can’t articulate.

That hasn’t stopped Catherine from feeling embarrassed, sometimes when meeting new people. Morgan might stroke a stranger’s face or take off running. She’ll jump up and down and holler. When Catherine’s describing her sister to people who haven’t met her yet, she’ll slip in some clues that she has special needs, maybe noting that she runs in the Special Olympics.

“I’m always going to have to keep tabs on Mo; and my family, once they’re gone, she’ll come with me wherever I am,” she said. “It’s not a burden, but I know it’ll be hard and sometimes I get a little upset at that. It’s never at her. It’s, What did she do to deserve this? What did we do to deserve this?”

When Catherine was in third grade she started a buddy program, pairing neurotypical kids with developmentally disabled ones, between her school and Morgan’s. This year she’s joining a committee for the 2018 Special Olympics USA Games, which Seattle is hosting.

She also wants to go to the University of Notre Dame, maybe live in Europe, and become a lawyer. But the responsibilities looming ahead can still make her anxious and sometimes angry. It’s always in the back of her mind. What about Morgan? While her friends finish college and set off to start their own lives, hers will be staked to her sister.

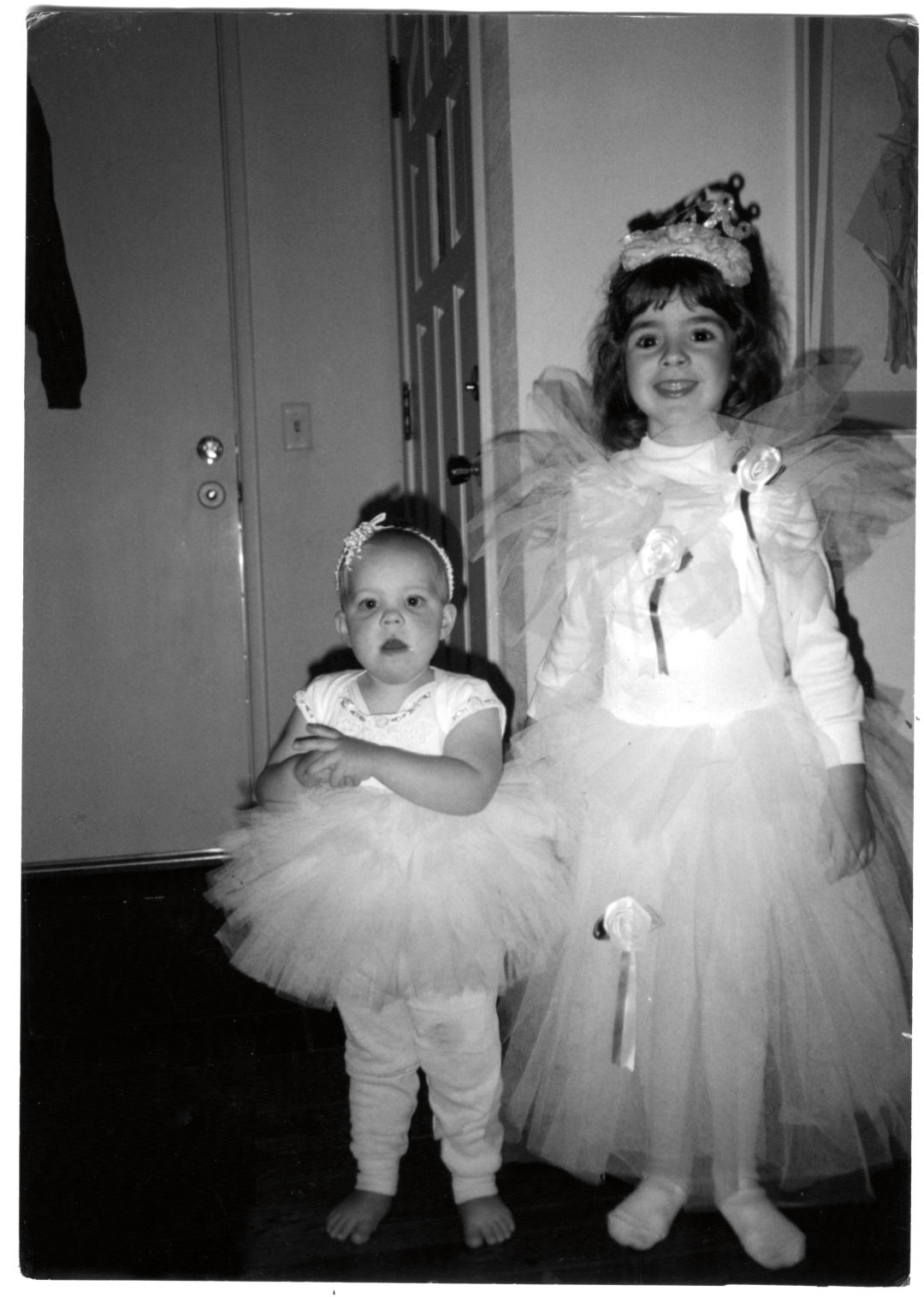

“Ellie,” age 4, in May 1994.

There are small white scars on my hands and wrists where Ellie scratched me when we were children. Our mother’s arms are covered in them, wounds from going to battle as Ellie thrashed and fought in the hallways, crying before bedtime while I pulled a pillow over my ears. Ellie’s meltdowns could be triggered by noises like the sound of flip-flops slapping the ground. “Take off your fucking flip-flops,” she screamed at our mom. Certain sights make her gag. She has to close the kitchen blinds when she eats, for example, so she can’t see the grass. The smell of Christmas trees makes her nauseous.

Other times, when her anger and angst bubbled into a violent froth, we wouldn’t know why. When she was about five, she’d get into the van after school, buckle her seatbelt, and start kicking the back of our mom’s seat as hard as she could. She wouldn’t say it but she was being bullied, and the anxiety of going into the classroom was debilitating; she’d retreat into herself, freezing physically and emotionally, a vacant look coming over her face. At least until the bell rang. Back at home, she would spiral. Once, when she was a little older, she pushed the kitchen table through the window.

But really, she had struggled since the beginning. Her first gasp of air out of the womb wasn’t followed by another, and when the nurses at EvergreenHealth in Kirkland finally put an oxygen mask to her face the hose disconnected from the tank with a hiss. My father, who had emigrated from Ireland in his early 20s, fell to his knees and started praying loud and fast. Ellie turned blue and then pink, when she finally started to breathe. Everyone in scrubs reassured my parents that she would be fine.

She nevertheless spent much of her life sidelined, missing milestones starting when she was an infant with low muscle tone. She didn’t walk until she was 17 months old and for many months after she didn’t talk much at all. A battery of tests determined she was mildly to moderately delayed, and that she always would be. A doctor didn’t confirm she was on the spectrum until she was in second grade, the year she asked for a pet rat.

“If that was my daughter, I would have her sent to her room for a timeout,” my mom recalls a neighbor saying as Ellie lost control yet another time. I haven’t always been understanding either.

I had just graduated from high school the year our parents separated, and when our mother celebrated her birthday in August, I wanted it to be nice, a sparkly night that would stand out in that bleak summer. I made a reservation at an Italian restaurant in Seattle, and the three of us dressed up and drove across the bridge. Soon after we were seated Ellie, who was 14, started to fuss and cry until it reached a crescendo and we left before our food came. I was close to crying myself by then and glared at her as we piled back in the car. She had calmed down in the time it took to drive back to Bellevue, to the Cheesecake Factory (her idea), and as she scoured the thick menu there, I told her that she had ruined our mom’s birthday.

Memories of my own birthdays are colored by her crying, drawing the attention away from me. As a teenager, when I would fight with my father, Ellie would wail, overwhelmed by the conflict. I can’t even act out without it becoming about her, I thought. Before she could really speak, she called me “Hi,” a la Annyong Bluth.“My name’s not Hi!” I once yelled, running away from her with a friend as she tried to join us.

Back then I just wanted her to leave me alone. I hadn’t yet started to think about the future and what our lives would look like, still bound together decades later.

When Mark Bruell, 62, moved in with his sister Stephany and her husband in 2004 she asked Mark to write down what he wanted on a piece of paper. Friends, he said, and to be able to go places and do things on his own. Stephany understood.

“He wanted to be included,” she says. “He wanted a life.”

She’s tried to give him the one he envisioned. Mark sleeps in the basement of Stephany’s Portage Bay home, emerging in the mornings to grab the newspaper and chat. Stephany, who’s 65, makes his dinners for him but he likes to eat alone, and will retreat downstairs to watch Jeopardy! She hires companions to take him on outings and he likes to walk to University Village, where many of the shopkeepers know him. Mark has developmental delays and other health problems, and though he was never formally diagnosed with autism, Stephany suspects he’s somewhere on the spectrum.

Their mother was a nurse who fought to find a place for her son. It was the 1950s and parents were encouraged to institutionalize children like Mark, Stephany said. But he lived at home and Stephany and her older sister were expected to look out for him.

Stephany still does.

She thinks a lot about what his life is going to look like when she can no longer care for him. For now, he won’t consider retiring from the Haring Center, where he volunteers to take out the recycling and tidy rooms. When Stephany suggested it recently he got quiet, and then said, “I can’t. There’s no one who can do my job.” Fifty years ago, he was one of the original students at the center, an inclusive early childhood program at the University of Washington that then served teenagers too.

“Sometimes when parents wonder what’s going to happen to their child,” she says, “they can point to Mark and say, ‘Your child can have a rich, full life.’”

Sitting in Stephany’s living room, a comfortable airy space that overlooks the bay, I thought the same was true for her. She had just carved space for Mark in it.

Catherine had told me that she didn’t know anyone like her, who would eventually take care of a brother or sister with needs as severe as Morgan’s. Before reporting on this story, I too had never talked at length to anyone who was or would be responsible for their sibling. I can’t remember even meeting someone else in that position. But as Stephany walked me to the door, she told me I had a friend that was going through the same thing as I was.

It took me a moment to realize she was talking about herself.

Stephany had been concerned that I hadn’t heard about the Sibling Support Project, a Seattle-based program dedicated to the brothers and sisters of people with developmental and mental health concerns, so a few days later I called Don Meyer, who runs it. About halfway through our conversation, I started to tear up. Meyer listed common concerns among the siblings he’s interacted with, including a fear I’d had since I was a child: that if I have kids, they’ll have a disability. Then he named another familiar feeling: guilt.

Many of the siblings Meyer has encountered experience guilt for feeling resentful that the world seems to revolve around their brothers and sisters. Or they’re embarrassed by them, or they’re angry. There’s also worry over what will happen when their parents die, and pressure to not burden parents with more problems while they’re still alive.

Check, check, and check. I have felt all of those things.

Yet writing this now I find myself rushing to make sure readers know how much I love my sister, how rich my world is because of her, how I’m a better person because of her. Every parent and sibling I interviewed said something similar.

Meyer started working with siblings of people with autism in 1982 and today he’s the only person he knows of who is devoted to the work full time. He thinks that’s evidence of short shrift siblings have received from policymakers and service providers over the years even though they’ll face many of the problems parents of people with autism are challenged with now.

“I see situations where parents have done a not especially good job of planning for the future for their child with special needs,” he said delicately. “A lot of siblings worry mightily.” But if they’re informed, validated, and not isolated as they grow up, he said, they’re more likely to remain lovingly involved in the lives of their brothers and sisters.

Catherine Brewer was in fifth grade when her parents first floated the idea of her becoming her sister’s guardian. Erin, her mother, thinks constantly about the future and what Morgan wants and needs. Her quality of life is their duty, Erin says.

“But it’s Cate’s quality of life,” she adds. “If I have a plan, a trust funded, and the right connections and experts, I trust Cate. She loves her sister, and she will be the guardian eventually. But she has to live her own life.”

The author (right) with her sister, “Ellie.”

Once my mom suggested that I had moved and stayed in Texas so that less would be asked of me. I was indignant and rattled off the reasons I lived 2,000 miles away: community, a job, and adventure among them. I’ve since wondered if I did in fact run away, worried the walls were closing in on me with each passing year. Feeling like I only had so much time to live my life. I’m twice Catherine’s age and I’m still afraid of losing my freedom.

After graduating from Western Washington University, I took off for Paris, where I interned at a newspaper and then traveled, to Spain, Israel, and other countries I’d never visited before. I didn’t come home again until I had to, for Ellie’s high school graduation. Two months later, I moved to Texas, a state I found just as foreign as France. But over more than five years, I made it a home, finding a job as a reporter in Austin and buying a house. Ellie visits about once a year, indiscriminately using the word y’all and thrilling whenever she sees someone riding a horse on the street. She loves it there, but she also wants me to come home. Several times a year she asks me when I will. Once she told me she’d find a job for me, hoping that would yank me closer.

Young adults with autism tend to develop in their 20s the way neurotypical people grow in their teens, says Dr. Gary Stobbe, a neurologist at Seattle Children’s Autism Center. As Ellie’s gotten older, her vocabulary has grown and so has her confidence. She’s tried harder to harness her emotions. She’ll go to her room instead of berating someone for wearing sandals. Once too overwhelmed to even order food from a waiter, she now says “thank you” after nearly every interaction at a restaurant.

I’ve grown up too. And it’s changed how I reflect on some of our struggles as sisters. As she panicked when my dad and I argued, she was also trying to protect me, rushing to my defense. She’s always been sensitive to the world around her and now I think of her like a sponge, absorbing everything until it becomes too much and she has to squeeze it out.

Once, after I chastised her for using the word “retard,” I asked her if she understood what it meant. Yes, she said. It meant that her brain didn’t work right. More recently she told me that she decided she doesn’t want to have autism anymore. “How do I get rid of it faster?”

At 26, she has a part-time job at a cafeteria where she cleans the salad bar and refreshes the condiments. She laughs with her coworkers and finally feels popular. She no longer eats lunch alone. She has a boyfriend, a handsome young man with Down syndrome, who sits with her. Someday she’d like to marry him. She daydreams about learning to drive and adopting a child. She says she’d maybe like to try working in an office where she imagines pulling a higher salary. “So that you don’t have to worry about money when mom dies and you have to take care of me.”

In May 2016, five years to the day after our grandmother passed, another death drew me back to Bellevue. When I called Ellie on FaceTime to tell her the news, she had just returned from bowling practice—she competes in the Special Olympics—and she answered the phone with a big, happy grin. Her face crumpled when I said, “It’s Dad.”

Before I flew to Washington a few days later, I steeled myself for the funeral that needed to be planned, the decisions I had to make, the sister I had to comfort. “I need you,” she had texted me before I bought my ticket. But as Ellie resumed her routine and rebounded, I struggled. She was hanging up her laundry one morning when I opened my computer and found the reading I had been assigned to recite at the funeral mass in my inbox. Ellie heard me sniffling and poked her head around the corner. Then she dragged a chair next to me and silently wrapped her arms around my shoulders.

When I returned a couple of months later, it was to stay with Ellie while our mom went out of town for the weekend. I thought it would be an opportunity to learn more about taking care of her but I only had to remind her to brush her teeth and help her clip her hair back before work (she struggles with small motor skills). Every morning she woke up by herself without even an alarm clock and packed her breakfast before waiting by the window for the Access bus to pick her up. On the last night we made dinner together and then walked the dog to a nearby park. We sat looking at Lake Washington and talked about our mom’s upcoming birthday. Ellie had saved money and wanted to take her to a Mariner’s game.

A picture from game night shows the three of us smiling, me and Ellie flanking the woman we rely on in different ways. Ellie looks relaxed, leaning in, and comfortable in a sweatshirt. I was wearing shorts and unprepared for the cool temperature after the sun set at Safeco Field. But Ellie was—she pulled out a blanket she had packed just in case. As I covered my legs with it, our mom laughed.

“I always knew it would be like this with you two,” she said. When I asked her later what she meant, she explained that I didn’t bother to bring a blanket but Ellie thought that I might need one. Ellie worries about details like that. At night, she’ll close the blinds and turn on the lamps while I’ll grow distracted and work in the dark by the light of my computer. Ellie knows where I left my keys. Ellie will stuff everything she could possibly need in her backpack before leaving the house each day. And if she has time to make a pot of coffee before work, she will, because even though she doesn’t drink it she knows we do.

And when I wonder aloud if I’ll be prepared to step in when our mom does die, Ellie reassures me.

“You got this.”