Agent Jose Verdugo's workplace is vast: 1,100 square miles of hilly, sandy terrain surrounding Nogales, Arizona, the second-largest border-patrol station in the country. Depending on the day's assignment, he'll hike trails or drive along the boundary between the United States and Mexico. Some days he investigates human trafficking or drug smuggling. (Half of the marijuana that crosses the southwest border is captured in the Tucson sector, where Nogales is situated.) Other days Verdugo investigates a suspicious blip on a radar system that often turns out to be foul weather, or a rancher tending his land, or a stray cow.

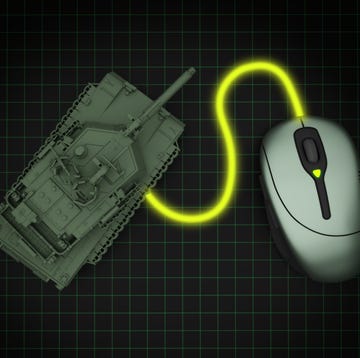

Over the years, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has used a series of strategies, some more effective than others, to monitor huge swaths of rugged terrain along the border. It needed a solution that would prevent agents like Verdugo from being deployed for false alarms, so they could chase and investigate narcos rather than livestock and be prepared for what they encountered when they caught up. This would require permanent sensors that could provide a clear picture to agents back at the station of what was happening in the field. The Integrated Fixed Towers (IFT) system, which includes radar and day and night cameras mounted on a series of towers along the border, promises to solve the problem. The radar and cameras transmit data over microwave link to the Nogales station, where agents determine an appropriate course of action. The system, which enables agents to accurately monitor areas previously unobserved, is, Verdugo says, like "turning on a light switch" along the dark, mysterious border.

The IFT is only the latest of the government's attempts to cover the southwestern border with sensors capable of detecting unlawful crossings. The previous setup, known as SBInet, was a network of newly designed radar, cameras, and heat and motion detectors, which was supposed to allow border-patrol agents to work from a common operational picture. Boeing won the contract in 2006, and the system was initiated across 53 miles of Arizona's Mexico border.

It quickly became a boondoggle. Total acquisition costs rose to a projected $1.6 billion, a staggering $1.4 billion more than initial estimated costs, according to the Government Accountability Office. It also didn't really work. The main problem was communication—the information transmitted to the command center was unreliable. It didn't operate well in the varied terrain of the Tucson sector, and was often triggered by bad weather, leading to false positives. In 2010, as costs rose, then Homeland Security secretary Janet Napolitano halted the program and asked border patrol to start over. "One of the lessons of SBInet was you're better off going small than big, and you're better off going off-the-shelf than innovative," says Christopher Wilson, a border-security expert and deputy director of the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Border-patrol officials came to the same conclusion and sought out preexisting, tested technology. The new approach, announced in 2011, would combine proven mobile surveillance, thermal imaging, and tower-mounted video technology. The request for IFT proposals called for sensors able to detect "a single, walking, average-sized adult" and provide sufficiently high-resolution video of that adult at a range of up to 7.5 miles in daylight and darkness.

The biggest defense contractors—including General Dynamics, Lockheed Martin, and Raytheon—all competed for the $145 million contract, which was awarded to Elbit Systems of America, the Fort Worth, Texas–based subsidiary of Israel's Elbit Systems. Elbit has deployed hundreds of miles of border-monitoring systems between Israel and Palestine and also provided multisensor surveillance systems along Israel's border with Gaza and Egypt. As of July, Elbit had completed construction in Nogales, and in September it crossed a major hurdle when the IFT system, tested by border-security agents, demonstrated the capacity to detect, track, and classify movement on the border. In other words, it works. Elbit's system is so specific that it can determine whether an individual is carrying a backpack or a long-arm weapon.

It's also designed to operate in the rugged Arizona desert. "Border control can break anything," says John Lawson, CBP acting section chief. "It's very difficult terrain to deploy technology in, and that's one of the benefits that we're anticipating. This system is going to be a lot more rugged than a lot of the previous things we've deployed." Now that the IFT has proved itself worthy, a second installation on the Arizona border is underway, with the ultimate plan of safeguarding the entire Mexico-facing stretch of Arizona's perimeter, pending congressional approval.

The IFT is only one part of the border patrol's effort to use technology to enhance security. The Arizona Border Surveillance Technology Plan, which includes the IFT, also uses remote video surveillance—day and night cameras for cluttered urban environments where radar is not as effective—and truck-mounted mobile sensors that can be moved when needed. Drones have been used to provide a bird's-eye view of vast stretches of border, and in 2012, the agency deployed a military wide-area camera attached to an aerostat, an airship tethered up to 5,000 feet off the ground. Originally used in Afghanistan, these cameras are capable of capturing miles of terrain in a single hi-res image. But officials say that all of the technology, including the IFT system, serves only to support the most valuable assets border patrol has: the agents. "Back in the early days, it was people looking for footprints on the ground," Lawson says. "We still do that." Only now, the agents stand a better chance of finding them.

With radar, day and night cameras, and thermal imaging, the new system is like "turning on a light switch" along the dark, mysterious border.

This story appears in the February 2016 issue of Popular Mechanics