The Reason Behind Colleges' Ballooning Bureaucracies

Universities’ executive, administrative, and managerial offices grew 15 percent during the recession, even as budgets were cut and tuition was increased.

BANGOR, Maine—Post-It Notes stick to the few remaining photos hanging on the walls of the University of Maine System offices in a grand brick building that was, at one time, a W.T. Grant department store, built in 1948.

The notes are instructions for the movers, since the pictures and everything else are in the midst of being packed up and divided among the system’s seven campuses.

Only 20 people work here now, down from a peak of 120, and the rest will soon be gone, too, following their colleagues and fanning out to the campuses. Disassembled cubicles and crates of documents are piled in the corners of the 36,000-square-foot space, and light shines from the doors of the few lonely offices still occupied. All of the agency’s three floors in the building—located in a quiet part of town near a statue of the Bangor native Hannibal Hamlin, the vice president under Abraham Lincoln—have been put up for sale.

It’s part of a little-noticed but surprising shift under way that suggests new resolve in some places to improve the efficiency and productivity of stubbornly labor-intensive higher education.

Surprising because statistics suggest the opposite is happening. The number of people employed by public-university and college central-system offices like this one has kept creeping up, even since the start of the economic downturn and in spite of steep budget cuts, flat enrollment, and heightened scrutiny of administrative bloat.

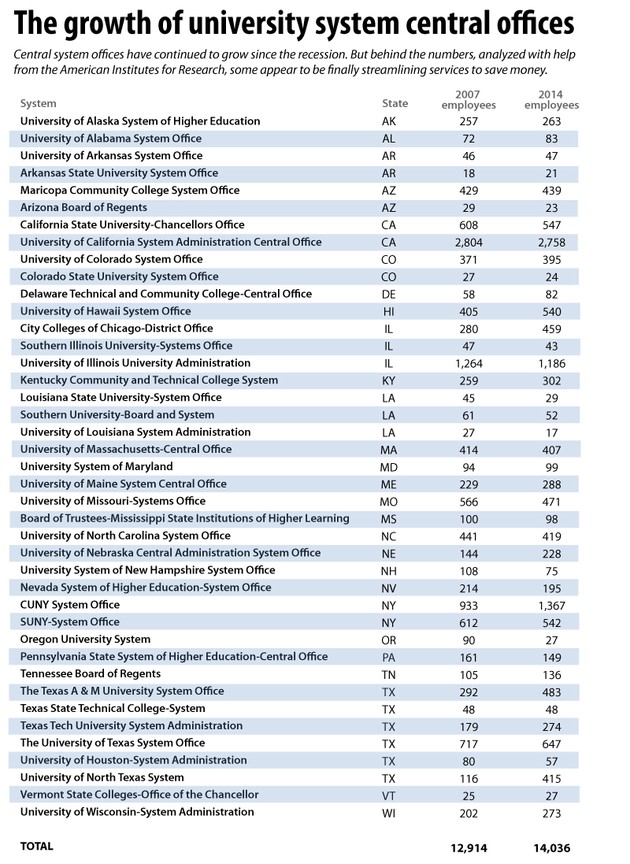

Critics complain these offices often duplicate work already being done on the campuses they oversee and employ scores of bureaucrats who have no direct role in teaching or research. From just before the recession until 2014, the latest year for which figures are available, higher-education central-system office staffs grew by nearly 4 percent, according to federal data analyzed by the American Institutes for Research in collaboration with The Hechinger Report.

When private, for-profit university headquarters and the regional offices of California’s unusually structured community colleges are excluded, the increase in staffs was almost 9 percent.

While there’s no breakdown about how much central-system offices contribute to the cost of running universities, one survey in 2010-11 by the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems put the average at $484 per full-time student. The highest per-student cost rang in at $3,336, though which system spent what was cloaked from public view. This continued growth has happened at a time when states have collectively cut their higher-education spending by 18 percent, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, forcing hikes in tuition.

The University of Maine System central office is among those that grew the most. It ballooned by 26 percent, despite an enrollment decline and budget cuts resulting in the termination of at least five academic programs and 51 faculty members—among what a spokesman said were 902 jobs eliminated.

But while the persistent rise in the number of central-system bureaucrats seems to suggest insensitivity to how much colleges cost to run and who is forced to pay, it’s behind these figures that a change turns out to be under way.

After years of promising to save money by streamlining operations, cutting duplicate staffs, and maximizing purchasing power, some university systems have been forced by political pressure and economic realities to finally start doing it.

That helps account for much of the growth in central-system offices—employees in once-separate departments whose positions have been moved there from the campuses. This centralization could eventually help curb costs that contribute to rising tuition, some observers say.

“You’re moving functions from the campus to the central office, but you may save money ultimately,” said George Pernsteiner, the president of the State Higher Education Executive Offices Association and himself a former chancellor of the Oregon University System.

In Maine’s case, under what’s called the One University Initiative, the system has consolidated the budget, legal, personnel, information technology, insurance, purchasing, and other departments from its seven campuses. To save more money, the central-system office staff is being shifted from that now-nearly empty Bangor building to the campuses themselves, which had free space available.

Overall, system officials say, this reorganization has resulted in a 37 percent decline in the number of administrators at the universities and will save about $6.1 million a year.

Given its budget crisis, the chancellor, James Page—who was overseeing the transition— said, the system had little choice but “to become more efficient, to become more responsive … We had enormous redundancies that were inefficient, and we couldn’t take advantage of economies of scale.”

This is happening in other places, too. While each state is different, “There are many systems that have had to take advantage of those kind of efficiencies,” said Rebecca Martin, the executive director of the National Association of System Heads. “There are more people doing it and more people beginning to do it. Part of it is just the pressure to do better with the resources that we have.”

With its state-budget allocation cut by more than a third, the Louisiana State University System, for example, did away entirely with its separate system office and got rid of the position of system chancellor. Now all the campuses fall under the control of the president and top administrators of LSU’s flagship Baton Rouge campus. In a mirror image of what’s happening in Maine, some campus employees may soon move into newly vacant space in the building that once housed the system office at the edge of the campus.

Louisiana policymakers “saw [the budget problems] as an opportunity to take a look at something that had been on some people’s minds, which was, ‘Why do we have a system office and a major campus that both have CEOs located in the same footprint?’” said Dan Layzell, the LSU vice president for finance and administration. “Why do we have to have both a president and a chancellor? Why can’t one person do both jobs?”

Those are questions that have come up in Hawaii, too, for which the federal data show that the number of central-system office staff rose 33 percent between 2007 and 2014. One reason for the jump, officials there say, was a bookkeeping change that added the central administrators of the state’s community colleges to the total for the first time. There were also increases in the number of information-technology employees and managers to oversee the paperwork required by a growing amount of research.

A consultant hired by the Board of Regents to consider whether the system office and the job of system president should be eliminated recommended against it. However, the consultant found many redundancies, and a reorganization is underway to consolidate more services, said a spokesman, Dan Meisenzahl. “We’re just not getting a blank check any more and we have to show that every dollar given to us is spent wisely and efficiently.”

Not everyone is persuaded that public universities have fully embraced centralization.

“The people who run these universities have as their primary motivation their own self-interest,” said Howard Bunsis, a professor at the Eastern Michigan University College of Business. “It’s been a constant process to get administrations to think differently.”

Even if some system offices are finally taking over functions once left to the campuses, any widespread savings—as measured by collective reductions in positions and spending—have yet to show up.

The number of executive, administrative, and managerial employees on university campuses nationwide continued its relentless rise right through the recession, up by a collective 15 percent between 2007 and 2014, the federal data show. From 1987 to 2012, it doubled, far outpacing the growth in the numbers of students and faculty. At many four-year institutions, spending on administration has increased faster than spending on instruction, according to the Delta Cost Project, which tracks this.

Now among the reasons some of these system offices continue to grow, many administrators insist, is that employees from the campuses are being transferred to them as a way of centralizing services or cutting other costs.

The University of Colorado System, for example, added staff to manage a new self-insurance program, which a spokesman said has saved $27 million since 2011. The number of employees at the district office for Chicago’s City Colleges grew 64 percent, but a spokeswoman said that was the result of centralizing functions previously handled by its seven separate colleges, which is saving $19 million a year.

When the University of North Texas System added a fourth four-year campus, “It made even greater sense to consolidate,” said the spokesman, Paul Corliss. Otherwise, he said, “We were going to have to build another staff.”

That realization triggered the system-wide centralization of information technology, human resources, purchasing, and payroll—more than doubling the size of the central office in the process, according to the federal figures. The change also saved $5.6 million by prompting the renegotiation of IT contracts and the replacement or elimination of redundant technology; $1 million through collective buying; and $1.5 million by automating payroll and other services, Corliss said.

This hasn’t happened everywhere. The University of Alaska System Board of Regents, for example, commissioned a study into whether its three principal campuses should be melded into one accredited institution with a single administration; compiled by the interim chancellor of one of the schools, it recommended against the idea.

But the Delaware Technical and Community College did combine its three campuses into a single accredited institution with a central administration under which there is now one office instead of three.

“I don’t think it’s a huge leap” to conclude that steps like these are being forced by budget pressures, said Judi Sciple, the vice president for institutional effectiveness and college relations at Delaware Technical and Community College.

They’re still not easy, she said.

“I will be very honest: It took a while for the campuses to catch up that we weren’t having separate governance,” Sciple said. “It does take a few years to change a culture.”

This post appears courtesy of The Hechinger Report.