What Actually Happened in Kashmir?

Why the details of the latest India-Pakistan battle over the territory are still murky—and why this time was different

Deep into the moonless night of Wednesday, September 28, according to Indian officials, two battalions of Indian commandos stole over the Line of Control, the de facto border that separates India and Pakistan in Kashmir. On foot, they reached a series of so-called “launch pads”— improvised structures where jihadist militants had assembled, so that they might more easily slip across border to conduct attacks in India. Using grenades and rocket-launchers, the Indian commandos destroyed the launch pads, killing an unknown number of militants in the process. By 4:30 a.m., the commandos had returned to Indian soil; on the way home, one soldier was wounded lightly by an exploding mine.

The mission marked the culmination of days of anxiety along the Line of Control. A week and a half earlier, militants in Pakistan had attacked an army base in Uri, a region of Kashmir that lies six miles east of the Line of Control, killing 19 soldiers—the highest death toll suffered by the Indian military in a terrorist assault in decades. Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, vowed that the episode “would not go unpunished.” His home minister called Pakistan “a terrorist state”—one further iteration of the common knowledge that Islamabad’s security apparatus foments and facilitates cross-border terrorism in Kashmir.

A week after India’s raid on the launch pads, the immediate alarm that it would tip India and Pakistan into war has faded. On Monday, a Pakistani government spokesperson announced that the national security advisors of the two countries had spoken on the phone, and that they had agreed to try to defuse tensions along the Line of Control. But the operation marks an inflection point in Modi’s Pakistan policy, one that he began outlining three years ago, when he started campaigning to be prime minister.

Details about the commando mission remain oddly sketchy. A short statement issued by the Indian military said that its intelligence agencies had received “very specific and credible information” about an impending terrorist attack. The commandos’ “surgical strikes at several of these launch pads” caused “significant casualties,” the statement added; it specified nothing further. (Additional facts about the operation have only emerged in subsequent, anonymously sourced media reports.) In a twist, Pakistan denied altogether that such an operation even transpired. The night of September 28 was quiet except for a near-routine bout of shelling and some exchange of small-arms fire across the Line of Control, Pakistani officials insisted. Correspondents for the The New York Times and the Washington Post managed to get close enough to Pakistan’s side of the Line of Control to interview villagers who testified that no Indian troops had crossed over.

If these surgical strikes did indeed occur, they wouldn’t have been India’s first inside Pakistan-held territory. In recent decades, India’s army and intelligence agents have penetrated the Line of Control to hit key positions occupied by terrorists or Pakistani soldiers, as part of the longstanding tussle over Kashmir. In his book Avoiding Armageddon, the Brookings Institution’s Bruce Riedel recounted the spectacular 1988 explosion of an arsenal just outside Rawalpindi, nearly 200 miles from the border with India. “In 2012 two former Indian officers told me that it was their service that sabotaged the facility to punish Pakistan for helping the Kashmiri and Sikh rebels,” Riedel wrote.

What was different about the operation on September 28, however, was the Indian government’s eagerness to talk about it. An Indian army official held a press conference hours after the attack concluded. The home minister chaired a meeting of all national political parties to give them details about the mission. India’s foreign secretary, S. Jaishankar, briefed the ambassadors of 25 countries within a day of the surgical strikes. Through India’s long engagement in Kashmir, this was the first time the government publicly announced the results of an ostensibly covert maneuver.

The energy of this communication suggested that the strikes were, in large part, conducted with a domestic audience in mind. In recent months, Modi has faced increasing pressure to uphold his reputation for toughness, as well as his Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) credibility for giving Pakistan no quarter. India rattled its sabres less for the sake of deterrence—similar strikes in the past had no impact on Pakistan’s fondness for nurturing militants and implicitly sanctioning their violence—and more as a public-relations exercise.

When Narendra Modi began his election campaign, he projected himself as the quintessential strongman, planning to whip the government into shape through the sheer force of his character. He spoke frequently about the need to deal with Pakistan and its state-backed terrorism firmly, and to recognize the limits of mere diplomacy. “A lot of people die in terrorist attacks. Pakistan beheads our soldiers on our soil. Yet Delhi is holding talks with Pakistan over chicken biryani,” Modi scoffed in September 2013. The BJP, rooted in Hindu nationalism, has traditionally advocated greater aggression against Pakistan. While the party’s manifesto for the 2014 election mentioned Pakistan only twice, one of its key foreign policy planks left little room for doubt: “In our neighborhood we will pursue friendly relations. However, where required we will not hesitate from taking [a] strong stand and steps.”

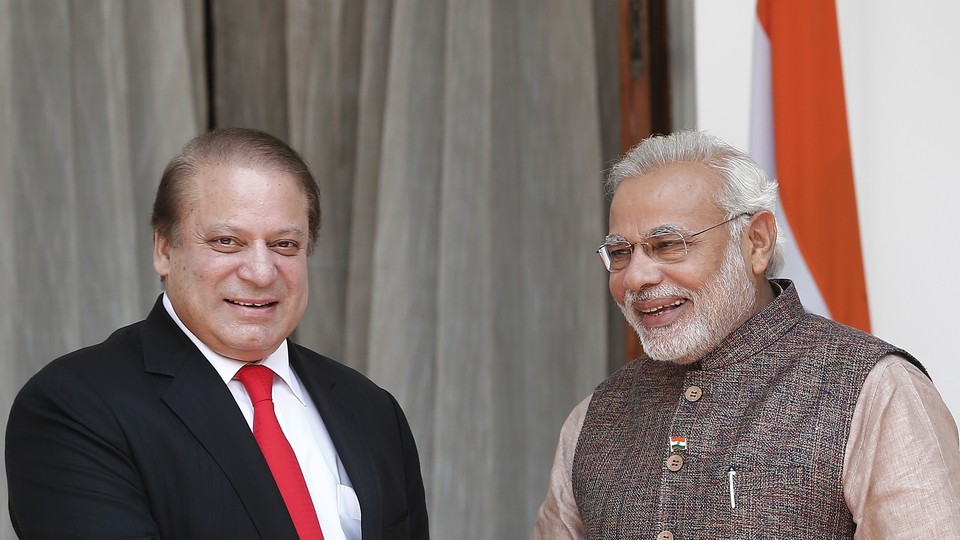

But foreign policy is too large a battleship to turn around that easily, and the BJP was coming to power after the 10-year prime ministership of Manmohan Singh, who was keen on maintaining civil and pacific relations with Pakistan. After Modi’s victory in May 2014, his stance softened. He invited Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, as well as other South Asian leaders, to his inauguration ceremony in New Delhi; later, Sharif sent along a sari as a gift for Modi’s mother. On the sidelines of the Paris climate talks, the two leaders agreed to begin a comprehensive dialogue. Weeks later, on Sharif’s birthday, Modi paid a surprise visit to Lahore while returning to India from Afghanistan. “That’s like a statesman,” Modi’s foreign minister tweeted approvingly. “This is how it should be with neighbors.”

Modi maintained his pacified tone even after an attack on an Indian Air Force base on January 2. Six militants climbed over the perimeter wall of the station in Pathankot, near the border in Punjab, and in a gun battle that lasted for hours, seven military personnel were killed. In the aftermath, India and Pakistan agreed to postpone a scheduled round of talks. In a gesture without precedent, the Indian government also permitted a five-member investigation team from Pakistan to visit Pathankot. When the team’s report claimed that the attack was a “false flag” operation, orchestrated by India to malign Pakistan, India shrugged off these conclusions. Three weeks later, New Delhi resumed talks with Islamabad.

The decision to press on with diplomacy—“love letters,” as Modi scorned the process in 2009—was applauded by several Indian commentators as mature and cool-headed. Within the BJP’s nationalist support base, however, it was interpreted as weakness. For the party’s diehards, it deviated too much from their sustaining mythology. On social media, disappointed outrage-merchants called Modi “spineless” and “incompetent.” The Shiv Sena, one of the BJP’s coalition allies, accused the government of being deluded. “Whoever becomes the prime minister, they immediately become obsessed with Pakistan and how to engage with it despite grave provocations,” Sanjay Raut, a Shiv Sena parliamentarian said. “I didn’t expect it from this government, but it too seems to be going down the same road.” Ajai Sahni, a counter-terrorism analyst, wondered: “Where is our national pride?”

Since then, Modi has weathered a torrid summer in Kashmir. At least 70 civilians and two policemen were killed in demonstrations that began in early July, after Indian troops shot dead a popular young militant named Burhan Wani. Crowds congested the streets of Kashmir’s towns, throwing stones and demanding that the army shrink its presence in the valley or even that India leave Kashmir altogether. For weeks on end, security forces seemed unable to suppress the protests altogether, despite the extensive use of pellet guns, a weapon classified as “non-lethal” and capable of spraying dozens of small metallic balls at high velocity. (One hospital in Srinagar had to perform more than 400 eye surgeries on pellet-gun victims, sparking protests from doctors over the weapon’s indiscriminate use.) The attack in Uri occurred just as the protests across Kashmir had abated somewhat. It was within this climate that the Indian government ordered the midnight excursions into Pakistan-held Kashmir.

The risks of runaway escalation from that operation have now diminished. The genuine quandary now appears to be the Indian government’s policy of future reaction. Power once projected is difficult to contain. In openly announcing this set of strikes, the Indian government has committed itself to responding in like fashion to the next attack, or the one after that, or the ones further still down the line. In the attempt to reap immediate political capital through the display of a strong hand, the government may well have locked itself into a single course of action.