After five years in a cramped refugee shelter in southern Germany, Ashkan finally found a room to rent. It is newly renovated and cheap, if on the small side and a bit out of town. The 22-year-old chef, who fled Afghanistan after the Taliban killed his father, immediately set about decorating it with an Afghan bedroll, a Persian rug and an Afghan flag. The low building that flanks his new home looked unremarkable to him. But to a German, the distinctive, elongated shape is rather unsettling, and for good reason. Ashkan’s new home is in a part of Dachau, a former concentration camp where the Nazis murdered 41,500 people, some in agonising medical experiments. Under the Nazis, the complex of buildings where Ashkan lives was used as a school of racially motivated alternative medicine, surrounded by a slave-labour plantation known as the “herb garden”. Asked if he feels uneasy about the site’s history, Ashkan replies with a resigned smile: “I just wanted a roof over my head.”

With shelters and social housing under pressure even before the current refugee crisis, the town of Dachau, near Munich, has resorted to housing about 50 of its most vulnerable inhabitants – among them homeless people, as well as refugees like Ashkan – in the former herb garden. It is just across the road from the main Dachau camp, which is surrounded by watchtowers and walls topped with barbed wire. Custodians of the former camp argue that the herb garden should be turned into a memorial site. Town officials say they need the space for those with nowhere else to go. Trapped in the middle are people like Ashkan.

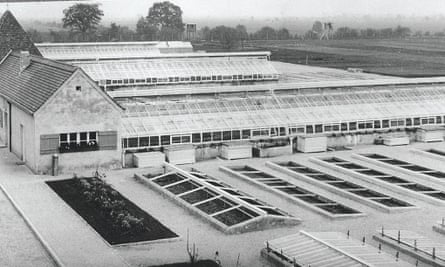

He tells me he knows little about Germany’s Nazi past, and has had no time to visit the main memorial site: “I go to work, I come home, I go to work.” The herb garden looks bleak, despite the autumn sun. A few dilapidated greenhouses and a memorial slab are reminders of its past. Children play in the courtyard. Only a short train ride away in Munich, Germans are welcoming tens of thousands of Syrians, Afghans and Iraqis with cheers and “Willkommen” banners. But in Dachau, as in many other small German towns, the situation has been desperate, and not just this year. Recent headlines have focused on Germany’s hastily improvised emergency shelters – in exhibition centres and beer tents – to house new refugees. However, longer-term accommodation for those whose asylum claims are being processed, or who have been granted asylum, has posed just as much of a problem. In July, the city of Bochum caused an uproar when it announced plans to house up to 100 asylum seekers in containers in a cemetery. There have been calls to settle more refugees in former East Germany: many buildings there lie empty as locals move west, where the jobs are. However, the east has also seen furious protests against such shelters, and several refugees in Munich told me they were afraid to go there. Last year, 47% of all racist attacks in Germany took place in the former GDR, although it is home to only 17% of the country’s population.

But no other housing options are as controversial as former German concentration camps. Earlier this year, officials in the towns of Schwerte and Augsburg caused an uproar when they considered putting up refugees in external sites of concentration camps. Augsburg scrapped the plan, while authorities in Schwerte said the refugee shelter turned out to be next to – not on – the historical site. In Dachau, on the other hand, town officials and camp custodians are still at loggerheads over what to do with the buildings in question: remember past wrongs, or address present needs?

“For me, it’s not very welcoming to house refugees in a place that symbolises torture and death,” says Gabriele Hammermann, director of the Dachau concentration camp memorial site. Her office is next to a vast square in the main camp, where starving inmates once shivered for hours during roll call. While we discuss her ideas for the herb garden, which include using it as an exhibition space, visitors from all over the world are walking across the square. With 800,000 tourists a year, Dachau is one of Germany’s most visited camp memorial sites. An inscription on a memorial stone reads: “Think About How We Died Here”.

Under the Nazis, the herb garden across the road was dedicated to developing alternative forms of healing. It was part of a bizarre attempt to invent a “German” medicine, since mainstream medicine was thought to be influenced by Jewish doctors, and therefore ethnically tainted. In the greenhouses, fields and laboratories around the buildings, up to 1,600 mostly Jewish slave labourers grew and processed medicinal herbs and edible flowers for the German population and the Wehrmacht. After their long, exhausting shifts in thin uniforms, often drenched by the rain, the prisoners returned to the main camp.

The Nazis’ notorious medical experiments, such as submerging prisoners in icy water until they died, occurred only in the main camp. But in the herb garden, inmates suffered many other forms of cruelty. Lower-ranked guards, or “kapos”, sometimes played a deadly game with them. They would snatch a prisoner’s cap from his head, toss it across the lines of SS guards, then tell the prisoner to go and fetch it, knowing the SS would shoot him if he did; if he resisted the order, he was also punished. A photograph in the Dachau camp archive shows the body of Abraham Borenstein, a Jewish milliner from Warsaw, who was shot dead in the herb garden in 1941 by SS guards.

Hammermann has just returned from Israel, where she attended the funeral of a Dachau survivor. The circle of survivors is shrinking fast, another reason why she feels it is important to protect what is left of the memory of camp life. After the war, when housing was scarce and Germans were keen to suppress the memory of the Holocaust, local authorities had used parts of the camp as a refugee shelter. The herb garden continued to be farmed by a series of companies until it was gradually turned into an industrial park. Now only the small complex of buildings and the greenhouses remain as silent witnesses to the horrors of the past.

Current residents of the herb garden have little time to reflect on its history, however. One Romanian woman, a mother of three, tells me she came to Germany three years ago because she could not find work back home. She spent the first night sleeping rough. The next day, town officials helped her move here. Asked if she minds its history, she cries in despair: “Where else should I live with my three children? On the street? This is better. What can I do?”

Her own concerns are with the present. “It’s a catastrophe here, the people are aggressive, they drink,” she says, as her small children play in the dark corridor, hugging her legs and running up and down between the racks of drying laundry.

Florian Hartmann, the mayor of Dachau, defends the current use of the herb garden as necessary. He says it is the town’s duty to find accommodation for the homeless in the face of a long-standing housing shortage. “The buildings in the herb garden are used to house people who can’t afford a flat at market rates,” he writes in an email. “They’re the more vulnerable members of our society. In that way, the buildings with their historical burden can be used for a socially meaningful purpose.”

Germany expects to receive 800,000 refugees this year, its warm welcome in stark contrast to the British government’s coolness, even hostility. Syrians have celebrated chancellor Angela Merkel as their “compassionate mother” and chanted “thank you, Germany” on the streets. But last week, Munich’s mayor said his city had reached its limit. Germany reinstated border controls with Austria to stem the flow, suspending the Schengen agreement for free travel that is a cornerstone of the European Union.

Reactions within Germany have been similarly mixed. There were heart-warming scenes of volunteers in Munich giving stuffed toys to Syrian refugee children. But elsewhere in Germany, images of burning asylum shelters and terrified refugee families told a different story. Germany’s interior ministry has counted 202 attacks on refugee shelters in the first half of 2015, as many as in all of 2014, and the German media has reported dozens more such attacks in July and August. In a survey this month, 46% of East Germans and 36% of West Germans said the high number of refugees arriving in Germany made them afraid.

In Dachau, Ashkan says he has never experienced any direct aggression in the five years since he arrived in Germany. But he has experienced more subtle xenophobia. “It’s been hard to find a flat,” he says. “Whenever I say, I’m from Afghanistan, the reply is: OK, right… no.”

In the cramped and noisy communal shelter where he lived before, he was sharing a room with up to five people – Afghans, Iraqis, Syrians, Egyptians. Some spoke Arabic, some Farsi, some tried to communicate with each other in broken German. As Ashkan’s frustration mounted, an Afghan friend told him about a place for the homeless run by the town. The rent was only €60 (£45) a month, it was clean, it was private. Ashkan moved in only a week before my visit. He liked it so much he told another Afghan friend about it, too. Over lunch with his 20-year-old Afghan girlfriend, Dania, he tells me about his previous life, in Herat, where his father was a local official.

“I had everything: a motorbike, my family, friends whom I saw every day. I lived like a prince,” he says. But after the Taliban killed his father, they threatened him, too. He is grateful for the life he now has in Germany. “Here you don’t have to worry that you leave the house in the morning, and you’re dead,” he says. “You don’t have to worry that someone will suddenly kill you. That’s better.”

Some have speculated that Germany’s friendly embrace of refugees is a way of expunging historical guilt, and while this interpretation might seem uncharitable, or to let other countries off the hook, many Germans do see a connection between past crimes and current responsibilities.

“It wasn’t our fault, but our grandparents were part of it,” says Peter Himmelsbach, a 28-year-old wholesale merchant from Heilbronn, who is visiting the Dachau memorial site for the first time. “In a way, the refugee crisis is a chance to do something better. On the other hand, people expect too much from us because of our past.”

A group of air force officers-in-training in blue uniforms respectfully remove their blue berets as they enter the barracks. Lieutenant Roman Lehmann, an earnest 27-year-old who is leading the group, explains that a visit to a former concentration camp forms part of the basic military training in Germany.

“It’s a way to try to ensure this doesn’t happen again in the future,” he says. “Concentration camps as such happening again, that’s probably unlikely. But if you look at the situation of refugees in Germany right now for example, there’s been a rise in rightwing tendencies. We’ve seen arson attacks on refugee shelters. We need to develop this sense of: this is where it can lead, we’ve already experienced this before.”

Like many other German towns, Dachau has made huge efforts to help refugees. The small community of only 45,000 inhabitants is housing about 350 refugees in the communal shelter. It is planning to open another shelter for up to 100 people in the coming months, and may see numbers rise given the current influx. Faced with such pressure on the available space, the town may not rehouse the Dachau camp residents any time soon. Hammermann, the director of the memorial site, says she could accept a compromise that would still see some of the buildings used as residential space, and the rest for exhibitions and seminars. Negotiations between the town and the state of Bavaria over the future use of the herb garden will take place this winter.

While officials are pondering the future of their home, Ashkan and Dania are caught in their own private attempts at reconciling the past and the present. Dania came to Germany from Afghanistan with her mother four years ago. For some time, she believed her father and two younger siblings were dead, drowned in the sea during the passage to Greece. Miraculously, she found them again; they had become separated and travelled ahead. Now they are all in the same place, though for administrative reasons, Dania and her mother live in a flat, and the others in the communal shelter. Her mother works at McDonald’s; Dania is training to be a dental assistant. In Afghanistan, she had to stop going to school after the Taliban poisoned the food at a nearby girls’ school, but in Germany she caught up quickly.

Both she and Ashkan speak excellent German. They are models of successful integration, having achieved what the thousands waiting in emergency shelters in Munich and elsewhere are still dreaming of. Yet Dania can’t shake off the trauma of the harrowing journey to safety and the hard years of assimilation that followed.

“I can’t feel joy any more,” she says with an air of helplessness. “I used to tell myself, one day I’ll have a flat, one day I’ll be safe, one day I’ll have an education. Now I have all that, and I can’t enjoy it.”

She and Ashkan tease each other over their stir-fry lunch in a casual display of affection that would be unlikely in their conservative homeland. Gradually, Dania’s sadness gives way to a smile, and by the time they see me out, into the corridor where Nazi officials once studied herbal medicine, they seem relaxed and at ease. As I leave, Ashkan takes Dania’s hand and gives her a kiss on the cheek. For a fleeting moment, they look like any young couple in their first shared flat, giddy and full of hope for the future.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion