Selling on the streets is hard. It doesn’t matter if one is slinging handbags or doughnuts, shish kebab or art – vending is for those who are tough. The hours are long, the pay low and precarious. Competition is cutthroat, and cops drown you in tickets. Worse, the space legally available to vend keeps shrinking. Which is why, on a rainy summer afternoon, two dozen street vendors gathered in Times Square to demand their place in the city.

The group was barely noticeable amid the crush of tourists, private security and grubby ersatz Spider-Men. Their signs were handmade; some presented simple demands: more permits, fewer tickets and restricted streets, and an end to the 20ft rule that keeps vendors from working near building entrances. Others insisted the vendors were workers with families to feed.

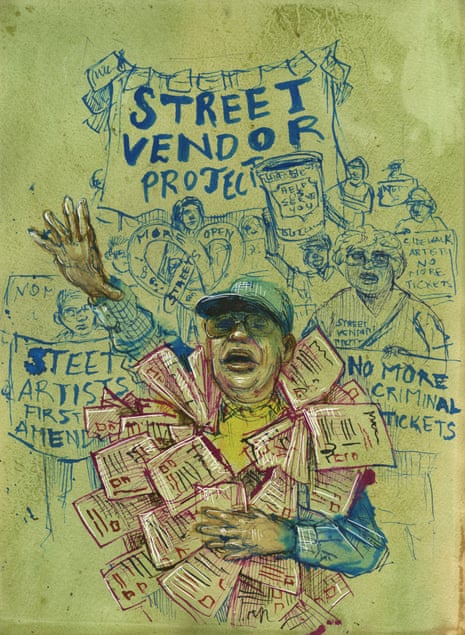

Osama Khatlan strode the front of the crowd. He wore a cape made from the hundreds of tickets he and other vendors had received for various offenses such as “vending in a restricted area”.

An Iraqi artist in his mid-50s, Khatlan is a lifelong activist. Declined entry to university for refusing to sign a Baathist loyalty pledge, Khatlan learned his trade illustrating for communist newspapers, and spent the late 1970s resisting Saddam Hussain alongside Kurdish guerrillas in Iraq’s north. While Khatlan exhibits his fine art internationally, he makes his living in part as a portrait artist in Times Square. He began organizing with other street artists informally in the 1990s, after other vendors attempted to threaten a Haitian artist out of his spot. Khatlan intervened and physically defended him.

Through the years, he also witnessed police harassment and arrest of his colleagues. During one such arrest, police complained to Khatlan that street vendors made New York resemble Baghdad.

“I’m from Baghdad,” he answered furiously.

The group Khatlan addressed that rainy day was a cosmopolitan group – a Latina burrito vendor, Chinese artists who make graceful name paintings, a west African handbag seller working in Queens, as well as a smattering of organizers. To the chant of “vendor power!” and waving banners, they headed downtown.

The march snaked down 8th Avenue, until it arrived in front of the Midtown South precinct police station. The officers eyed them suspiciously. Out came the barricades. Khatlan began another speech: “We sell art to showcase the beauty of this great city. We are not criminals!”

Despite their timeless presence in New York – where, according to a report by the Institute for Justice, they contribute $293m annually to the economy – street vendors are embattled on all sides: by the police, by the brick-and-mortar storeowners who view them as unfair competition, by the bureaucracy that they believe strangles their ability to make a livelihood.

Cops slap vendors with tickets that can eat up half their take-home pay. BIDs (Business Improvement Districts, or areas where business owners pay an extra tax to fund services) deploy private security to hassle vendors, and use their influence with the city to lobby for the closure of more streets. To BIDs, vendors like Khatlan are flies in the ointment of the sleek corporate neighborhoods they hope to build. To vendors, who are working class and predominantly immigrants, it’s a battle for more than survival.

They’re fighting for the right to be ambitious in New York.

In the early 1990s, Donald Trump led a jeremiad to close Fifth Avenue to street vendors. “The street-peddler plague is infecting the entire city of New York,” he said a few years earlier, in 1987. His words could speak for many members of the city elite.

New York glorifies entrepreneurship. We love the hustler, the poor boy or girl who made good. We’re the city of Jay Z and Madonna. We fetishize the scrappy businessman who bleeds for his dream. Yet as the city becomes more gentrified, and the police ubiquitous, there’s less and less space for poor people who work for themselves. This goes double if those people are brown, immigrants or can’t speak English, like most of the protesters in front of the 8th Avenue police station.

After a half hour, the station sent out a detective.

“Why are you here?” he asked Khatlan.

“We are here to say please respect us, respect us as business owners,” Khatlan answered. He demanded to know why he kept receiving criminal charges while doing his art.

The officer smirked. “The police department isn’t in charge of legislation.”

The vendors presented a petition. The police moved them to the other side of the street. They stayed for another half hour, beneath the slow drizzle of summer rain. Time passed, work called and soon the protest dissolved into the city.

A labyrinthine bureaucracy governs a street vendor’s life. Fifty-four pages of rules regulate food sellers, covering health rules, limiting them to certain streets, even forbidding them from tucking their licenses into their shirts. If vendors sometimes don’t fully understand the rules, police know them even less, leaving a huge margin for miscommunication, error and quota-fulfilling tickets.

In 2015, the city’s environmental control board wrote 18,744 vending violation tickets.

“Vendors are kind of sitting ducks,” Sean Basinski told me. “They are out there in the same spot every day. Imagine that you are a police officer and you need to write a ticket to somebody … There are so many rules [for vendors]. They are either breaking one or you could say that they are breaking one. They are almost definitely going to be an immigrant who is going to be scared of you, and they are not going to file a complaint against you.”

Basinski is the director of the Street Vendors Project (SVP), the group that called the Times Square demonstration. Basinski founded SVP in 2001 when he was just 23, after a summer working as a burrito vendor during law school. The Giuliani administration had just closed many streets to vendors, and Basinski became involved in a wave of organizing.

One of SVP’s major goals is to persuade the city to increase the amount of permits it issues. Because of first amendment protection, artists and booksellers need no license to sell on the streets, and in New York, disabled veterans also have the right to vend. Everyone else needs a permit. The city caps these at 3,000 and the waiting list stretches for decades, so frustrated vendors turn to the black market, where one vendor told me that the $200 permits can go for up to $20,000.

SVP, which has 2,000 members, functions at once as an activist group, professional association, and legal aid society for vendors. They maintain an emergency fund for vendors, a small business lending program and an annual food cart competition. At their monthly meetings, vendors organize around grievances, network and give each other moral support.

On the legal front, the SVP has won some major victories, including the reduction of a vendors’ maximum ticket from $1,000 to $250 in 2013. SVP’s staff lawyer helps vendors fight these civil tickets, but they don’t have the resources to represent their members in criminal court. No clear, public data is available on the number of vendors charged with misdemeanors, but the vendors I spoke to reported it was a constant concern. Khatlan has received 60 criminal tickets, as well as 90 civil ones. Most were dismissed, but a few times, he was sentenced to attend a class, or waste a day stamping envelopes or cleaning streets.

Unlicensed vendors also face potentially violent arrests, or worse: in 2014, SVP members marched in solidarity with Eric Garner, a Staten Island man who died after officer Daniel Pantaleo placed him in a chokehold during an arrest.

Immigrant vendors who don’t speak English face particular difficulties, said Angela Ni, a legal intern with the Street Vendors Project. Ni got involved with the organization at 13, interpreting for her father, a Chinese immigrant who drew portraits in Times Square. Many of the artists her father worked with had been newspaper illustrators in China, and some studied at the Beijing Academy of Fine Arts, but in America, their inability to speak English led them to practice their trade on the streets.

Over the last 10 years, Ni watched the already tense relationship between the artists, the police and the BID deteriorate. “They should feel protected by the police, but they feel persecuted,” she said. Banned from most Times Square streets before 7pm, artists work till past midnight for between $50 and $100 a day, but see up to half their incomes swallowed by tickets.

This is what happened to De Zhao, who has drawn caricatures of tourists in Times Square for the last eight years.

I met Zhao at the Midtown community court, where he was dealing with a charge for “vending on a restricted sidewalk”. Through a translator, Zhao spoke about the discrimination endured by Chinese artists, who “don’t have any way of explaining themselves or fighting back”. Zhao described a squad of six cops who he says often targeted him, shoving arbitrary tickets into his hand without bothering to speak to or look at him. When he asked for explanations, the police just wrote more tickets.

“The police need to be more concerned with getting the bad guys, with helping people instead of oppressing them,” he said, frustration making him speak faster. “But what can I do? I don’t understand any English.”

The Midtown community court was founded in 1993, during the start of efforts to “clean up” Times Square. It is sold as a kinder, gentler, “problem solving” court, where defendants are sentenced to community service, classes or rehab rather than incarceration. At first, police rounded up the sex workers, touts and three-card Monte dealers who gave Times Square its seediness – but street vendors were also on the list.

The court is a public-private partnership, and from the beginning received significant financial contributions from the Fifth Avenue Association, a local BID.

New York’s first BID hit Union Square in 1984. They’ve since proliferated wildly. New York now hosts 72, more than any other city in the country, and the relationships between BIDs and the police have always been close. A Yale study released a year after the court’s foundation wrote “the fact that strong private interests are making significant financial contributions to the court has caused many criminal justice officials to voice questions about the propriety of such contributions. Many of the people interviewed expressed their concern that the court was the direct result of a rich special interest buying its own system of justice.”

Claims of undue influence are also raised by Midtown community court conditions panel meetings that take place between the DA, judges, police and members of local BIDs. Though technically open to the public, these meetings are not advertised, and it took the Street Vendors Project considerable time to find out when they are held.

Basinski, who attended several of them, described a judge who drilled police on how to write tickets that wouldn’t get dismissed. (The Times Square Alliance BID declined requests to comment on this article.)

Videos become the vendors’ testimony to their experiences.

Mohammed Omar, a kebab cart vendor, showed me a cellphone video footage he’d taken to document harassment by the BID’s private security. In the video, the guard approached Omar’s kebab cart aggressively, saying something I couldn’t make out. “Every day you bother me,” shouted Omar. When he saw Omar was filming him, he covered his face.

Omar, who’s also a board member of the SVP, told me that two weeks before I met him in July at the Urban Justice Center’s offices, a police officer tried to ticket him for selling during restricted hours. When he explained his cart was closed, the officer barked at him to shut up, and when, as SVP advocates, he took out his camera to document the interaction, the officer threatened him with arrest, then slapped him with another ticket.

Omar started working on the streets at 22, selling vegetables in his hometown of Port Said, Egypt. Business flourished, and he soon owned a clothing store but in 2011, he packed up his wife and five kids and moved to America. He didn’t mention the revolution that broke out that year, telling me only: “America is a free country. It’s safe here for women to walk on the street.”

In New York, Omar got a job at a food cart owned by another Egyptian immigrant. If he was restarting his life, he figured, he might as well start on the street.

On Omar’s second day, a cop slapped him with five tickets he couldn’t hope to pay. Not knowing enough English to protest, Omar broke down in frustration. Seeing his distress, a fellow food cart worker told him about the Street Vendors Project. Soon, he was going to all their meetings, and, as his English improved, he joined the group’s board.

Omar owns his own cart now, and he’s taken on his friend’s daughter, Doa Abdolla, as an assistant. She has also joined the SVP leadership board.

New York tells itself a story. It goes like this. We are sharp-elbowed bastards who live in filth, surrounded by sewer rats, but with enough chutzpah, drive and determination, any of us can rise high enough to scrape the sky. It’s a myth, of course, and like all myths, it contains a narrow shard of truth. But with each year that shard shrinks, under the weight of gentrification, corporations and police. People like Khatlan and Omar fight to keep it alive.

It was Ramadan when I interviewed Omar, so he invited me to break the fast with him at his cart. Beforehand, I wandered through Times Square. A few topless showgirls were all that remained of the neighborhood’s outlaw cachet, but the streets are still theaters of working-class, largely immigrant ambition. Beggars demanded money for Viagra. Disabled veterans sold scarves. Touts hollered in praise of comedy shows, and dozens of blinking, smoking halal food carts offered cheap plates of protein that have fed generations of workers.

On the billboards, Global Capital reigned supreme, but the streets still surged with the human-scale hustle that has always defined this city.

When I found Omar’s stall, it was a few moments before sunset, and he was dying for a cigarette. As observant Muslims, he and Doa refrained from food and water during Ramadan’s daylight hours – a hard task in their line of work. In his free moments, Omar laid out supplies. Dates, a sticky fruit drink called Qmar-al-din, and skewers of lamb. Finally, the sky darkened. Despite the neon, we could make out the moon.

“Eat!” Omar demanded in Arabic and shoved twin mountains of food towards me and Doa. Then, he lit a cigarette.

Business was slow, he said. Vendors who owned several carts were stealing spots, and officers bedeviled him with tickets. But he worked for his kids, not himself.

Then he smiled. “I like the streets.” He said. “I think, if today is not good, there’s tomorrow. If this week is not good, there’s the next. If I take one day off, what can I do? Relax? That’s not life. The street is my life.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion