In the midnight hours leading up to the first US presidential debate, I sat up watching a rough cut of Adam Curtis’s new BBC documentary, HyperNormalisation, on my laptop. I thought – rightly – that the film would provide a suitable preface to Trump’s global horror show.

Like all Curtis’s documentary work, HyperNormalisation exists in a twilight between disturbing truth and restless dream. It charts an eccentric course through the choppier ideological currents of our times: the origins of Syrian apocalypse; the collapse of political middle grounds and the rise of nationalism; the meaning of Putin and Assad and the Donald himself.

The film is the most ambitious statement of Curtis’s methods and his message since his 2004 series The Power of Nightmares, which prophetically examined the ways that western governments exploit fears of terrorism to exert control. It is based on the premise that as a culture, perhaps as a species, “we have become lost in a fake world and cannot see the reality outside”.

Curtis suggests that the trending opposites of our times – the chatter of social media and the stricture of Islamic fundamentalism – represent a retreat from complexity into an existence that constantly reflects our desires and anxieties back to us. Meanwhile, genuine power to change lives becomes more opaque and distant, leaving large parts of the world helpless and desperate. Along the way, this being Curtis, his film offers tragicomic asides on Patti Smith and Occupy, BlackRock investments and The X-Files.

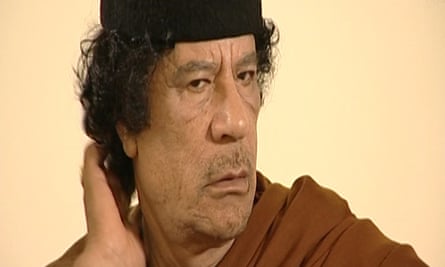

Critics of Curtis’s films say that his jump-cut techniques and abrupt mood changes in some ways cheat on the dogged legwork of documentary journalism. As ever here, shifts in geopolitics are routinely represented by a couple of seconds of arresting footage – the banality of puppet dictators is illustrated by Colonel Gaddafi checking his hair off camera; the emergence of me-culture becomes Jane Fonda giving up on activism and donning a leotard; to explain the collapse of communism there is a punch-up in a Soviet breadline. Arguments become impressionistic, the criticism goes, an atmosphere of conspiracy is not the same as the exposure of truth.

This criticism misses the point. Curtis’s films do not pretend to be definitive histories; rather they cast doubt on the possibility of that idea. They announce themselves clearly as subjective essays: “This is a story about …” is his opening mantra. His method is not only to attempt to understand the world, but to dramatise the ways we might go about understanding it. The films take the attention-deficit patterns of our 24-hour news cycle and try to impose some kind of persuasive narrative order on them – just as we try to do all the time. It is Curtis’s contention that in the constant distraction of our digital lives, we miss the larger play of ideas that shape them. His aim is to give us some clues about what those forces might look like.

The day after I watched the film, still groggy from Trump and his tax returns and Miss Universe, I had lunch with Curtis to talk about HyperNormalisation. As with his most recent documentary, Bitter Lake, about the postwar history of the west in Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, this will be launched exclusively on BBC iPlayer. He insists that this apparent demotion is wholly by choice – the open-ended format gives him licence to experiment and not be constrained by hour-long episodes (the current film is nearly three hours long).

“My editor says theoretically I can have a video that lasts up to 10 hours,” he says, with some boyish excitement about the possibility. “I’ve done this one with chapter headings. What was lurking in the back of my brain was that it is like a novel with lots of characters and you can jump from that part to that part and trust that it is all going to come together at the end.”

The model that Curtis’s films have always aspired to, he says, is that of the archetypal great American novelist, John Dos Passos, whose books he describes as “the most satisfying thing I have ever read”. The novelist pioneered a technique called “camera eye” which was, as it sounds, a rush of raw experience, and then spliced it with montage from newspapers and the lives of fictional characters.

“Why I love Dos Passos is he tells political stories but at the same time he also lets you know what it feels like to live through them,” Curtis says. “Most journalism does not acknowledge that people live at least as much in their heads as they do in the world.”

It is Curtis’s contention that it doesn’t matter if viewers get disoriented by what they see as long as they remain curious. “People are used to spending their lives searching for meaning in a completely chaotic way,” he says. “Information becomes a mosaic of questions on the internet. You search for something about whatever, Goldman Sachs, and five minutes later you are reading about a murder in Florida in the 1950s or something. You are quite happy with that.”

His films mirror that digressive quest, but loop continually back to his argument. One part of that argument is that Islamism was the unintended consequence of cold war power struggles. In this case, he traces the conflict in Syria back to the “shuttle diplomacy” of Henry Kissinger in 1974-75.

“Kissinger’s theory was that instead of having a comprehensive peace for Palestinians, which would cause specific problems, you split the Middle Eastern world and made everyone dissatisfied,” he argues. In the fallout from that policy no one, his film suggests, was more dissatisfied than Hafez al-Assad of Syria.

“I wanted to try to explain Syria,” Curtis says. His impression is that when we watch the footage from Aleppo the forces that have created that carnage seem all but unknown to us. This, he suggests, was deliberate. “The idea was that you couldn’t deal with Assad so you created an alternative reality in which Syria had no place. As a consequence, for example, it was hardly mentioned in the books about the rise of Islamism – so to our eyes the war seems to come from nowhere.”

You could argue that all historians and journalists are conspiracy theorists of one sort or another, collecting their collages of facts and imposing some narrative sense on them. Curtis’s style makes this process abundantly clear – but he still invites you to be seduced by the brilliant visual craft of his argument. In his netherworld of shifting certainties, characters – like, as he says, villains in a novel – come and go. Putin’s close adviser Vladislav Surkov takes on a kind of Rasputin role in this respect.

Surkov, whose previous career was as a director in avant-garde theatre, emerges, like Kissinger, as an arch manipulator of reality. “Surkov will invent dissident groups and fund them,” Curtis says. “He will fuel conspiracy theories, but that’s not new. His particular genius has been to let people know that is what he is doing. So whatever you see in the news: you just don’t know if it is ‘true’ or not. I noticed a headline in the Financial Times recently which said ‘no one understands Russia’s policy in Syria’. I thought: Mr Surkov.”

The goal of this manipulation, Curtis suggests, is to spread a state of bewilderment and powerlessness across the globe. A sense that nothing quite makes sense. Technology, in particular social media, becomes the ally of those forces. The global technology companies not only feed a mirror of our obsessions back to us, but increasingly try to normalise our behaviour – collecting data about our health and our habits and selling us a fixed idea of who we should be and what we should like (“if you liked that, you will like this”). The irony of this feedback is that it is fuels prejudice and is fuelled by anger. The more angry users are, the more extreme their emotional states, the more they click, and the more money rolls into Twitter and Facebook and the rest.

Trump is presented in the film as emblematic of this culture, certainly, but how exactly?

“My take on Trump is that he is an inevitable creation of this unreal normal world,” Curtis says. “Politics has become a pantomime or vaudeville in that it creates waves of anger rather than argument. Maybe people like Trump are successful simply because they fuel that anger, in the echo chambers of the internet.”

If Hillary Clinton gets elected next month, Curtis suggests, then the vaudeville will have played its role – the anger will have been expressed and changed nothing.

But what if Trump wins? “It means the pantomime has become reality and starts rampaging around. And then we are fucked.”

What’s the answer to ending or changing that pantomime?

“There has to be a new political vision that takes account of these forces,” he says. “I don’t know what that idea is and I don’t see it as my job to provide it. My job description is to make people aware of power. To let them see the forces around them. The things they don’t see.”

To this end Curtis has become a kind of heroic one-man depository of BBC memory. For the past few years he has been funding a former BBC cameraman, Phil Goodwin, to travel the world digitising all the unedited material in BBC cupboards and storerooms worldwide, the hours of rushes that got boiled down to a 20-second news report.

Goodwin spends weeks with a bank of six laptops and six tape machines collecting it all – and then brings it back and gives it to Curtis in plastic lunch boxes full of small computer drives. “So for example I have everything the BBC has ever shot for 60 years in Russia sitting on 58 terabytes of drives,” he says. “Phil is doing China next. Then Egypt. Vietnam. And then we are doing Africa. I aim eventually to have the last 50 years of unedited material. I could do an emotional history of the world.”

How does he avoid just being overwhelmed by the material?

“Some of it is indexed,” he says. “You have to do a bit of detective work. You just suddenly spot something. You have to intuit what people want. I think they want explanation.”

What does the BBC make of his obsessive methods?

“I made this film for £30,000,” he says. “So that’s fine by them.”

It’s his belief that we lack a journalism or art that can dramatise the shape of our globalised and digitalised world. “Dickens created these fictions that revealed the consequences of the industrial revolution, showed where the new power lay,” he says. “We are waiting for new stories to come along, new ways of telling them.”

He’s too modest to say so, but Curtis has himself, for 20-odd years, been feeling his way towards those new ways of telling. If you don’t know his work, HyperNormalisation is a great place to start.

HyperNormalisation will premiere on BBC iPlayer at 9pm on 16 October

Life and times

■ Born in Dartford in 1955, he is the son of cinematographer Martin Curtis.

■ Taught politics at Oxford University prior to pursuing a career at the BBC. Did a stint on That’s Life! before establishing his documentary style with a film for Inside Story: The Road to Terror (1989), which juxtaposed footage of Iran under Ayatollah Khomeini with the story of the French revolution.

■ Developed a signature style of television essay that told stories of contemporary culture using archive footage and pop culture imagery.

■ His work includes the series Pandora’s Box (1992), which looked at the dangers of technocratic solutions to political problems, and The Mayfair Set (1999), which traced the emergence of the global arms trade and the casino economy to a group of gamblers – James Goldsmith, David Stirling and others – who met at the Clermont Club in Mayfair, London.

■ His four-part film The Century of the Self (2002) examined how Sigmund Freud’s theories were put to use by his nephew, Edward Bernays, to create public relations and exert political control.

■ Won a Bafta in 2005 for his series The Power of Nightmares, which drew parallels between the rise of Islamism and American neoconservatism, ideas that he has continued to explore.

■ In 2013 he collaborated with trip-hop pioneers Massive Attack to create an immersive “gilm” – part gig, part film – Everything is Going According to Plan.

■ Bitter Lake, his first film shot exclusively for BBC iPlayer, came out last year and continues to be downloaded several thousand times each week.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion