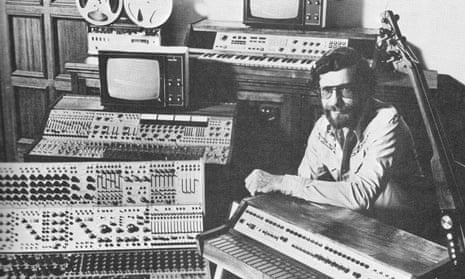

Don Buchla, the groundbreaking synthesizer inventor, has died age 79.

He was considered a true iconoclast with an uncompromising vision of what synthesizers could be. His impact on electronic music was vast; Buchla independently invented the first modern synthesizer, at the same time as Robert Moog, in 1963.

Although Moog is often credited with having invented the first modular synthesizer, Moog even admitted during his lifetime that Buchla was the first to have a full concept of how to put all the modules together to add up to an instrument. Buchla tended to avoid the term ‘synthesizer,’ preferring to use terms such as ‘electronic instrument.’

“He invented a whole new paradigm for how you interface with electronics – much more human, and a whole new thing,” says Buchla’s close friend Morton Subotnick.

Subotnick commissioned the first Buchla synthesizer in 1963 and had been friends and collaborators with Buchla ever since. “I put an ad in the paper and he showed up,” Subotnick says. “We wanted to make a new machine.”

The synthesizer, the Buchla Series 100, was finished in 1963. A string of pioneering new electronic instruments followed the Buchla 100 in the following decades; Buchla was actively designing and inventing up until his death.

“He was a genius and an adventurer – an adventurer in the real sense of the word,” says his friend, musician Bob Ostertag. “Almost everything he made was unprecedented.”

Buchla had a major impact on legions of electronic musicians. “Don Buchla gave me my electronic wings,” says the musician Suzanne Ciani, who first met Buchla in Berkeley in the late 1960s. “He was a consummate inventor who had genius, unswerving dedication and playfulness in his designs. ‘The Source of Uncertainty’ and the ‘Multiple Arbitrary Function Generator’ modules are two of my favorites. He never wore matching socks, but oddly, as an enthusiastic tennis opponent, always wore pristine tennis whites. I will treasure the days I worked for him, and hope to carry on the musical vision that he bestowed upon us.”

The musician Laurie Spiegel, another longtime friend of Buchla’s, says her life was changed forever after first encountering a Buchla 100 system in Subotnick’s old studio in New York’s West Village in the late 1960s. “I never figured out what exactly it is about Don’s electronic musical instruments that makes them so musical in feel,” says Spiegel. “I’ve used quite a few kinds of synths and systems. His were special, magical, musically magnetic somehow.”

Buchla played a key role in the 1960s California counterculture. He was involved with the Trips Festival in San Francisco in 1966, in which thousands of hits of LSD were given away for free to the audience. Buchla also helped build the Grateful Dead’s massive, legendary sound system, along with his good friend, the infamous chemist and audio engineer Owsley Stanley. “He was very close with Owsley,” says Ostertag. “Owsley and Don were the two hippie geniuses.” Buchla, he says, would sometimes sit underneath the stage at Grateful Dead shows in the 1960s and secretly play along with his synthesizer.

Through his life, Buchla was a true contrarian who never followed trends. He wanted to maximize creative freedom and possibilities for musicians, and he designed his unique instruments to reflect that. “It doesn’t bother me that my own ideas in particular have not been widely perceived,” Buchla said in a 1982 interview in Keyboard magazine. “It does bother me that the powers that be have such short-sighted views of what musical instrument design and development could be all about.”

Other inventors of electronic instruments looked to Buchla as a friend and inspiration. “Don was very much a rebel, defying convention at every turn,” says the synthesizer inventor Roger Linn. “It’s so nice to see the innovative ideas he developed 50 years ago being embraced by so many young electronic musicians.”

Subotnick called him a “wizard of interfaces”. Buchla’s philosophy was that a well-designed instrument would never become obsolete – to this day, his synthesizers are revered. The tendency, as Buchla argued in Keyboard magazine, was that when engineers designed instruments, “they design from the inside out. They design the circuits, and then they put knobs on them.”

“But if a designer expects to design legitimate instruments, he has to design them from the outside in,” Buchla continued. “He has to build the outside of the instrument first. This is what the musician is going to encounter. You cannot become obsolete if you design a legitimate instrument from the outside in.”

Buchla also made his own music and performed live, often with unexpected results. “One piece that is an insight into Don’s more silly personality was a piece where he had us wear giant sunglasses with musical staves printed on them, while we waited for popcorn on a hot plate to start popping, signaling when we should play our slide whistles or glissandos on our instruments,” recalls Joel Davel, who worked with Buchla for over 20 years.

His son, Ezra Buchla, a musician based in Los Angeles, remembered his father as “the most singular person”.

“The word ‘visionary’ doesn’t really do justice,” says Buchla. “He had no fear of anything – leaky boats, lightning storms, failure. He couldn’t have done what he did without a basic joy in his work and an innate intellectual generosity that swept people along.”