What O. J. Simpson Means to Me

His great accomplishment was to be indicted for a crime and then receive the kind of treatment typically reserved for rich white guys.

My reaction to O. J. Simpson’s arrest for the murder of his ex-wife Nicole Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman was atypical. It was 1994. I was a young black man attending a historically black university in the majority-black city of Washington, D.C., with zero sympathy for Simpson, zero understanding of the sympathy he elicited from my people, and zero appreciation for the defense team’s claim that Simpson had been targeted because he was black.

O. J. Simpson wasn’t black. He came of age in the 1960s—the era of Muhammad Ali’s opposition to the Vietnam War and John Carlos and Tommie Smith’s black-power salute at the 1968 Olympics. But the O. J. Simpson I knew, and the one poignantly depicted this year in Ezra Edelman’s epic documentary, O.J.: Made in America, recognized only one struggle—the struggle to advance O. J. Simpson. When the activist Harry Edwards attempted to enlist Simpson in the Olympic boycott, Simpson rebuffed him and later claimed that organizers like Edwards had tried to “use” him. Protest “hurt Tommie Smith, it hurt John Carlos,” Simpson said. Smith and Carlos were “standing on [Edwards’s] platform, [when] they should have been standing on their own platform.”

My view that Simpson existed beyond the borders of black America was based not merely on his narrow political consciousness, but on his own words. “My biggest accomplishment,” Simpson once told the journalist Robert Lipsyte, “is that people look at me like a man first, not a black man.” Simpson went on to tell the story of a wedding he’d attended with his first wife and a group of black friends. At some point he overheard a white guest remark, “Look, there’s O. J. Simpson and some niggers.” Simpson confessed that the remark hurt. But that wasn’t the point of the story. The point was not being seen as one of the “niggers.”

Simpson sought to be post-racial in a world that was not. His myriad achievements—becoming the premier running back in college football, the first NFL running back to rush for 2,000 yards in a season, one of the first black pitchmen for corporate America—did not mark the erosion of the great wall between black and white Americans. It marked Simpson’s individual success at hurdling that wall. Landing on the other side, Simpson, a product of public housing in inner-city San Francisco, found reinvention as a celebrity. He became wealthy. He courted the attentions and advice of affluent businessmen. And though he’d married Marguerite Whitley, who was black, the same year he arrived at the University of Southern California, he now courted white women. “What I’m doing is not for principles or black people,” Simpson told Lipsyte. “No, I’m dealing first for O. J. Simpson, his wife, and his babies.”

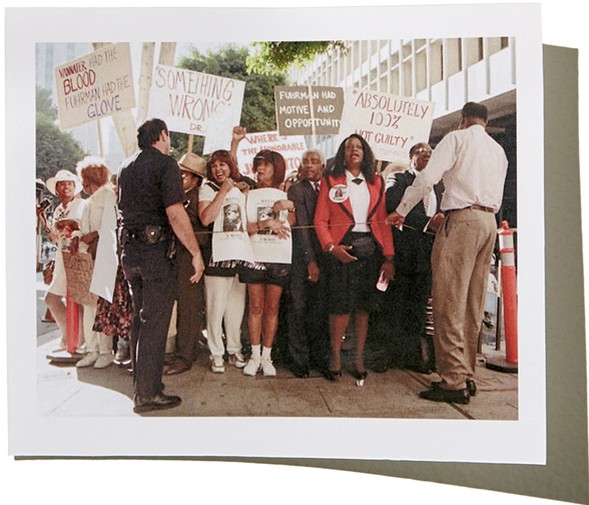

And yet, during his trial, whenever I walked the streets of D.C., I saw black people broadcasting their support as though he were one of them. Vendors hawked run o.j. and free o. j. simpson T‑shirts. Community activists, for whom Simpson had previously had no use, offered fervent defenses of him. When the verdict was announced, national-news cameras came to Howard Law School to record what turned out to be a jubilant response to Simpson’s acquittal. I found all of this very frustrating. I was 19 years old. I was the kind of militant black kid who flirted with Louis Farrakhan, Frantz Fanon, and veganism and who believed “What should black people do?” was a question that could be asked in earnest. The answer, I was sure, would open a new era of black excellence. The support of Simpson was a step backward. It struck me as unintelligent, politically immature, and ill-advised.

Two things, it seemed to me, could be true at once: Simpson was a serial abuser who killed his ex-wife, and the Los Angeles Police Department was a brutal army of occupation. So why was it that the latter seemed to be all that mattered, and what did it have to do with Simpson, who lived a life far beyond the embattled ghettos of L.A.? I vented in the school newspaper. “Since Simpson’s practices show he clearly has no interest in the affairs of black people,” I wrote, “the question becomes why do blacks have any interest in him?” In those days, I conceived of African Americans as a kind of political party, which needed only, in unison, to select the correct strategy in order to make the scourge of racism disappear. Expending political capital on O. J. Simpson struck me as exactly the opposite of the correct strategy. Looking back, I realize what eluded me. I had lived among black people all my life, but somehow I had come to see them as abstractions, not as humans.

I had not yet read Ragtime, the E. L. Doctorow novel that Simpson claimed to love. After his retirement in 1979, he began doing some acting and dreamed of playing Coalhouse Walker in the film adaptation of the book. Simpson felt the role of Walker, a black ragtime piano player turned revolutionary, matched his life. The parallels are strained—and in any case Simpson lost the role to Howard Rollins. But Simpson does resemble another character in the book, one whose feats explain the strange bond between Simpson and the black community. Doctorow offers a fictionalized Harry Houdini, whose escapes from straitjackets, bank vaults, piano cases, and mailbags thrill the poor people of the nation. He is jailed in Boston, imprisoned on an English ship, tossed into the Seine in manacles. Each time, he escapes. Houdini’s act allows him to make the greatest escape of all—out of poverty—though he eventually discovers that no amount of money will buy him the respect of the elite. The poor are enthralled by Houdini not because he organizes on their behalf, but because his exploits resonate with them: They know that their lives are trapdoored and trip-wired, that they too have been jailed, imprisoned, chained, and tossed into the sea. A Houdini performance was their life in miniature, with one heroic difference—he escaped.

Long before he led the police on a chase through L.A., Simpson had been an escape artist. His rare athletic talent freed him from an impoverished childhood, and brought him to USC on a football scholarship in 1967. Made in America, deftly capturing his athleticism, is alert to symbolism too, replaying Simpson’s manifold escapes while at USC and later with the Buffalo Bills. They are dazzling to behold. Simpson’s speed was enhanced not by grace but by awkwardness. In one frame he leaps past a defender, lands seemingly off balance, and then cuts across the field at full velocity. At several junctures, you expect him to fall, and the one time he does, the defender falls with him—but then Simpson, in a matter of milliseconds, glides to his feet and races off. He would angle himself against the earth, his hips flying one way, his head another. He seemed to run too high, with his chest exposed, presenting what should have been an inviting target for the defense. And yet he escaped.

Simpson was a running back, a position dominated by African Americans for the past half century—a fact that has often been invoked to boost racist thinking about the innate athleticism of blacks. More pertinent, the job of the running back—to escape—is the most basic of vocations, one that a kid from the projects can begin practicing in that first game of tag. Running also holds a special significance to a people denied violent resistance as a viable option, if only because it has always been the most potent tool available. The runaway slave is a fixture in the American imagination. As the writer Isabel Wilkerson notes in her account of the Great Migration, the blacks who fled the South during the 20th century “did what human beings looking for freedom, throughout history, have often done. They left.” There is also a less reputable history of fleeing among African Americans—the tradition of those blacks light enough to “pass” as white and disappear into the overclass.

Simpson’s great fortune was to reach the height of his powers in the 1970s, after the civil-rights movement, a time when one might enact the rituals of passing not by looking white, but by possessing qualities that white society envied. Simpson was a celebrity. He was handsome, articulate, and charming. He was identifiably black, but measured against the brashness of Muhammad Ali and the coiled rage of Jim Brown, his distinction was to radiate reassurance and respectability. In the successful series of ads he starred in for Hertz beginning in 1975, he was still running—only now through airports, an icon of social mobility, with white people cheering him on: “Go, O.J.”

An old friend of Simpson’s says in Made in America that Simpson was “seduced by white society.” Perhaps. But the seduction was mutual, and he used his football fame to gain access to white patrons eager to expose him to the finer things in life. “I took him places where I think very few black men had ever been,” Frank Olson, the former CEO of Hertz, says in the film. Simpson mingled with wealthy entrepreneurs at golf clubs where he was one of the few black members, or the first and only black member. He gave them the thrill of convening with a real sports hero at his mansion, Rockingham, nestled in the wealthy white suburb of Brentwood. Simpson’s social circle helped him amass a small fortune. By the 1990s, his net worth was estimated to be $10 million. He was the CEO of O. J. Simpson Enterprises, which owned stakes in hotels and restaurants, and he sat on four different corporate boards.

His pursuit of white women was profligate. In a telling moment in the documentary, Joe Bell, a friend of Simpson’s since childhood, recalls them slowly cruising down Rodeo Drive in the 1970s and being awed by the response. “Women come up, throw their arms around O.J., and just lay it on him,” Bell says. “Not just women. White women. Fine white women.” In 1977, Simpson began an affair with a beautiful blond 18-year-old, Nicole Brown, who came home from their first date with her pants ripped. “Well, he was a little forceful,” she told a friend. Two years later, he left Marguerite to pursue a relationship with Nicole. But the affairs continued: Bond girls, Playboy playmates, models, actresses, most of them white. For Simpson, the women on his arm were not women but bodies, ornaments, evidence of conquests—an outlook he had seen taken to its most violent conclusions in the form of neighborhood pimps. “Man, they’d beat a ho down right there on the street,” Bell remembers, laughing. “So that all the women would know this is the kind of treatment you’re gonna get if you don’t bring me my money.” Those women were black, but the basic notion of women as property knows no racial boundaries. Nicole Brown was proof to the world that Simpson, among the millions of black men caught in the maze of American racism, had risen above it. What sort of abuse—verbal and physical—was going on behind the mansion gates, almost no one, black or white, guessed. Or much cared.

The goings-on in the ghettos of L.A. were both more knowable and better explored—but not by O. J. Simpson. He eschewed involvement in any sort of politics that might tarnish his brand, and thus his pursuit of wealth. If it was easy for Simpson to forget the world he came from, that was partly because the world he now belonged to was invested in forgetting. In an incredible moment early on in the documentary, Edelman, off camera, asks a white USC teammate of Simpson’s what he remembers about 1968. A montage of violent events flashes across the screen—Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination, the raucous Democratic National Convention. Edelman then returns to the teammate, who says, “I think of winning all the games, getting O.J. famous, everybody on campus thinking it’s the greatest thing on Earth. That’s all we thought about. There was nothing else going on.”

But Edelman does not allow us to forget, because the Simpson story turned out to be intimately enmeshed with the story of black Los Angeles and its relationship with the police. This was the community the Simpson jury was drawn from, and ultimately the one that held his life in the balance. For years, much of the country has wondered how Simpson could possibly have been found innocent. An unspoken assumption underlies this conjecture—that the jury understood the legal system to be credible. What the film makes clear in piecing together a parade of victims beaten, killed, and harassed by the LAPD is that the predominantly black jury—quite rightfully—understood no such thing.

Even I, college radical that I was, grasped the LAPD’s brutality only abstractly. The officers were brutal because my own politics, and my own experiences with the police, suggested they would be so. But brutality understates what the LAPD did in those years: It didn’t just brutalize black communities; it terrorized them. The terror emanated directly from the top. Police Chief Daryl Gates was a drug warrior who once said at a Senate hearing that casual drug users “ought to be taken out and shot.” In 1982, after numerous deaths of black people had resulted from police use of choke holds, Gates commented, “In some blacks when it is applied, the veins or arteries do not open up as fast as they do in normal people.” The intensifying sense of constant injustice came to a head when four officers were videotaped ruthlessly beating Rodney King in 1991, only to be acquitted when they went on trial. Two weeks after King’s beating, a Korean American grocer shot a black customer, 15-year-old Latasha Harlins, in the back of the head. The grocer, convicted of voluntary manslaughter, received probation, a fine, and community service, but didn’t go to jail.

By the time Simpson came to trial, most of the black community in Los Angeles had ample reason to view law enforcement as lacking not just credibility but basic legitimacy. Victimization fed a loss of respect for law enforcement, and that loss of respect in turn transformed victims into victimizers. The footage of the protracted beating of a white man, Reginald Denny, who was pulled from his truck during the Los Angeles riots, is chilling. But when law enforcement becomes capricious, citizens are apt to resort to their own law, rooted in ancient impulses, tribal loyalties, and vengeance.

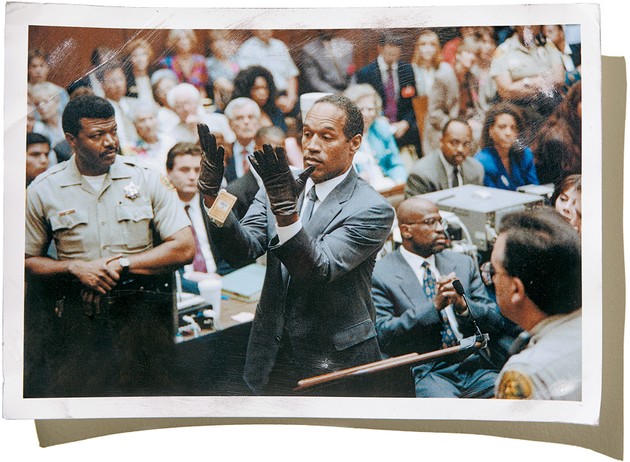

The beating of Reginald Denny was vengeance for the beating of Rodney King. And vengeance for King played a role in Simpson’s acquittal, according to one of the jurors, Carrie Bess. But revenge only partly explains Simpson’s last great escape. What I couldn’t fathom in 1994 was a reality that black people around me likely sensed and that Made in America brings into deeply discomfiting focus: that Simpson may well have murdered his ex-wife and her friend, and that the jury got it right in declaring him not guilty. When the LAPD collared O. J. Simpson, the police force had gotten its man. The evidence all looked so obvious to a lay observer: the vivid record of spousal abuse (“He’s going to kill me,” Nicole Brown Simpson yelled to an officer who responded to one of her many calls); the bloody shoe print, which matched shoes Simpson owned; the bloody glove found at the murder scene, which matched the glove at Simpson’s home; the blood on Simpson’s car and his socks and in his bathroom.

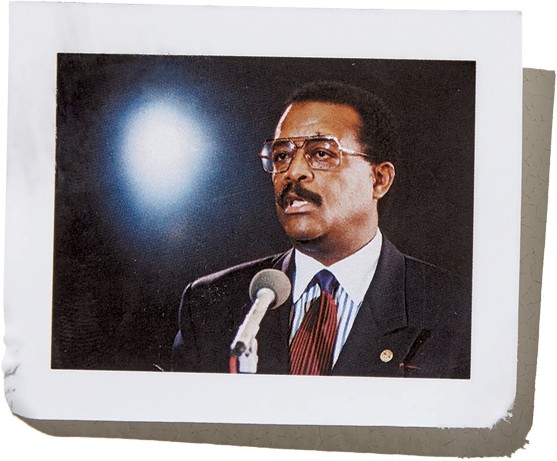

But juries are not merely lay observers, and the defense needed to neither wholly exonerate Simpson nor completely contradict all the evidence. His lawyers simply needed to instill reasonable doubt. The LAPD had spent decades seeding that doubt in the minds of people like those on the jury, the majority of whom were black women. To make sure the doubt was harvested, Simpson leaned on the kind of activist he’d long spurned. These days Johnnie Cochran is remembered almost in caricature, mocked on Seinfeld and derided as a race hustler. Back then, even my view of Cochran was shaped in part by the satirization of him on Saturday Night Live. Edelman resurrects a lesser-known Cochran, a hero to the black lawyers who’d been the prominent legal advocates in the fight against police brutality since the late 1960s. The New York Times called Cochran’s rage at police misconduct “all consuming.” Contrary to the portrayals of him in popular culture, that rage was genuine and directly acquired. In 1980, Cochran was pulled over by LAPD officers and instructed to get out of his car. His daughter and son were in the backseat. When Cochran stepped out, the officers had their guns drawn. The tension was defused only when the officers searched the car and found a badge—Cochran was then the third-highest-ranking official in the district attorney’s office. Cochran received a personal apology from the chief of police. “I never made an issue of it,” Cochran later wrote. “But I never forgot it.”

Simpson, who had turned his back on race men while making millions selling himself as inoffensive to middle-class white people, didn’t hesitate to empower one of them now that his life was on the line. Thus the Simpson defense team presented an ironic alchemy—an activist tradition that Simpson had rejected, fueled by funds that he’d garnered rejecting it. “O.J. had money to spend and a willingness to spend it on his own defense,” one of Simpson’s lawyers, Carl Douglas, says to Edelman. “This was a first for me.”

Whether I saw Simpson as black or not, racism pervaded his case. The role it played went beyond the evidence on display. Racism was not just blatantly revealed in the tapes of the LAPD detective Mark Fuhrman bragging about, among other things, beating black suspects, whom he identified as “niggers,” and explaining how he disregarded their constitutional rights. (“You don’t need probable cause,” Fuhrman said. “You’re God.”) And racism was not just confirmed by Fuhrman’s exposure as a perjurer who was then maneuvered into pleading the Fifth in response to grilling by the defense—including the pivotal question of whether he’d planted any evidence. Racism formed the substrate of the defense’s case: The notion that the LAPD might frame a black man was completely within the realm of possibility for black people in Los Angeles. Simpson’s legal team worked those preconceptions the way a boxer might work an opponent’s wound, relentlessly attacking the numerous flaws in an investigation and an evidence-collection process that were egregiously careless: the blanket thrown over Nicole Brown Simpson’s body, exposing it to fibers and the DNA of others in the house; the sensitive material collected bare-handed; the sample of Simpson’s blood stored in an envelope in an officer’s care and brought to Simpson’s house.

Errors that to white viewers could look like technicalities in what they presumed to be an abstractly “fair” trial tapped into fundamental questions of trust for black viewers, who saw up close a machine operated by humans striving for an ideal standard, but often falling woefully short. How many black men had the LAPD arrested and convicted under a similarly lax application of standards? “If you can railroad O. J. Simpson with his millions of dollars and his dream team of legal experts,” the activist Danny Bakewell told an assembled crowd in L.A. after the Fuhrman tapes were made public, “we know what you can do to the average African American and other decent citizens in this country.”

The claim was prophetic. Four years after Simpson was acquitted, an elite antigang unit of the LAPD’s Rampart division was implicated in a campaign of terror that ranged from torture and planting evidence to drug theft and bank robbery—“the worst corruption scandal in LAPD history,” according to the Los Angeles Times. The city was forced to vacate more than 100 convictions and pay out $78 million in settlements.

The Simpson jury, as it turned out, understood the LAPD all too well. And its conclusions about the department’s inept handling of evidence were confirmed not long after the trial, when the city’s crime lab was overhauled. “If your mission is to sweep the streets of bad people … and you can’t prosecute them successfully because you’re incompetent,” Mike Williamson, a retired LAPD officer, remarked years later about the trial, “you’ve defeated your primary mission.”

O. J. Simpson’s great escape still sticks in the craw of much of the country. Simpson’s lawyers are not praised as adept defense attorneys, but disparaged as unscrupulous flouters of the rules who played the “race card” in a case that should have been about science—no matter how poorly that science was deployed. Resentment continues to fester that Simpson was afforded the best defense money could buy, in the form of Cochran. “It offended me,” Marcia Clark, the lead prosecutor, says to Edelman, “because he was using a very serious, for-real issue—racial injustice—in defense of a man who wanted nothing to do with the black community.”

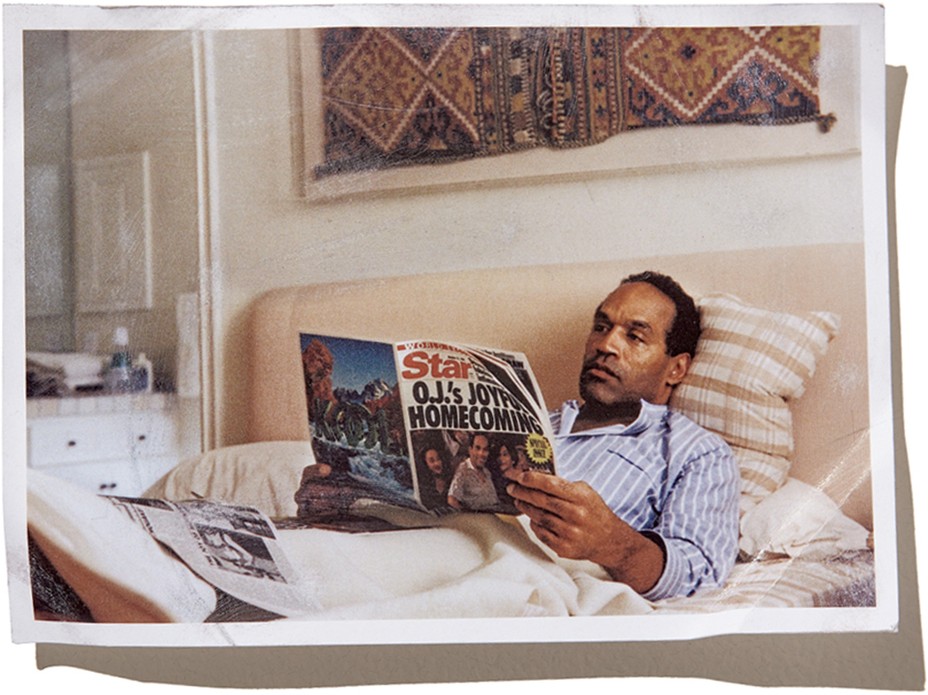

It offended me, too. Simpson should have been the last person in the world to reap a reward from the struggle waged against the LAPD. Months after he was acquitted, I watched him give a speech at a black church in D.C., where he was embraced by the local community. He was presented with traditional African garb. The black nationalist Malik Zulu Shabazz greeted Simpson as if he were the reincarnation of Malcolm X. I have not, in my life, ever felt much shame in being black. That was a moment when I felt it deeply.

I hadn’t yet learned that black people are not a computer program but a community of humans, varied, brilliant, and fallible, filled with the mixed motives and vices one finds in any broad collection of humanity. More important, I did not understand the ties that united Simpson and the black community. When O. J. Simpson ran from justice, returned to it, was tried for murder, and eluded justice again, it was the most shocking statement of pure equality since the civil-rights movement. Simpson had killed Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman. I suspected that then, and I am sure of it now. But he’d gotten away with it—in much the same way that white people had killed black men and women for centuries and gotten away with it.

The virtue of equality does not always feel like a virtue, because equality does not always run on the same axis as morality. Equality for African Americans means the right to be treated like anyone else—whether we’re doing good or doing evil. Simpson’s great accomplishment was to be indicted for a crime and then receive the kind of treatment typically reserved for rich white guys. His acquittal, achieved as incarceration rates skyrocketed, represented something grand and inconceivable for blacks. He had defied the police who brutalized black people, the prosecutors who tried them, the prisons that held them. He had defied them all, and in the process, much like Houdini, he escaped.

In 2016 we confront a new phase of the problem of police legitimacy. The Rodney King video was a shocker in its time. Now it seems that every week brings a new video of a black body being beaten and shot by the police. A flurry of government reports on policing in Ferguson, Cleveland, Baltimore, and Chicago have all delivered the same message—that racism has deeply infected American policing. Simpson is currently in prison for charges unrelated to the killing of Brown Simpson and Goldman. And yet the problems that moved those crowds of black people to cheer for a murderer remain. The same anger, the same fear of police remain. The elements that interacted to turn the Simpson trial into a spectacle are still with us, so that today, two decades after Simpson was acquitted, “the audience for escapes,” in Doctorow’s words, “is even larger.”

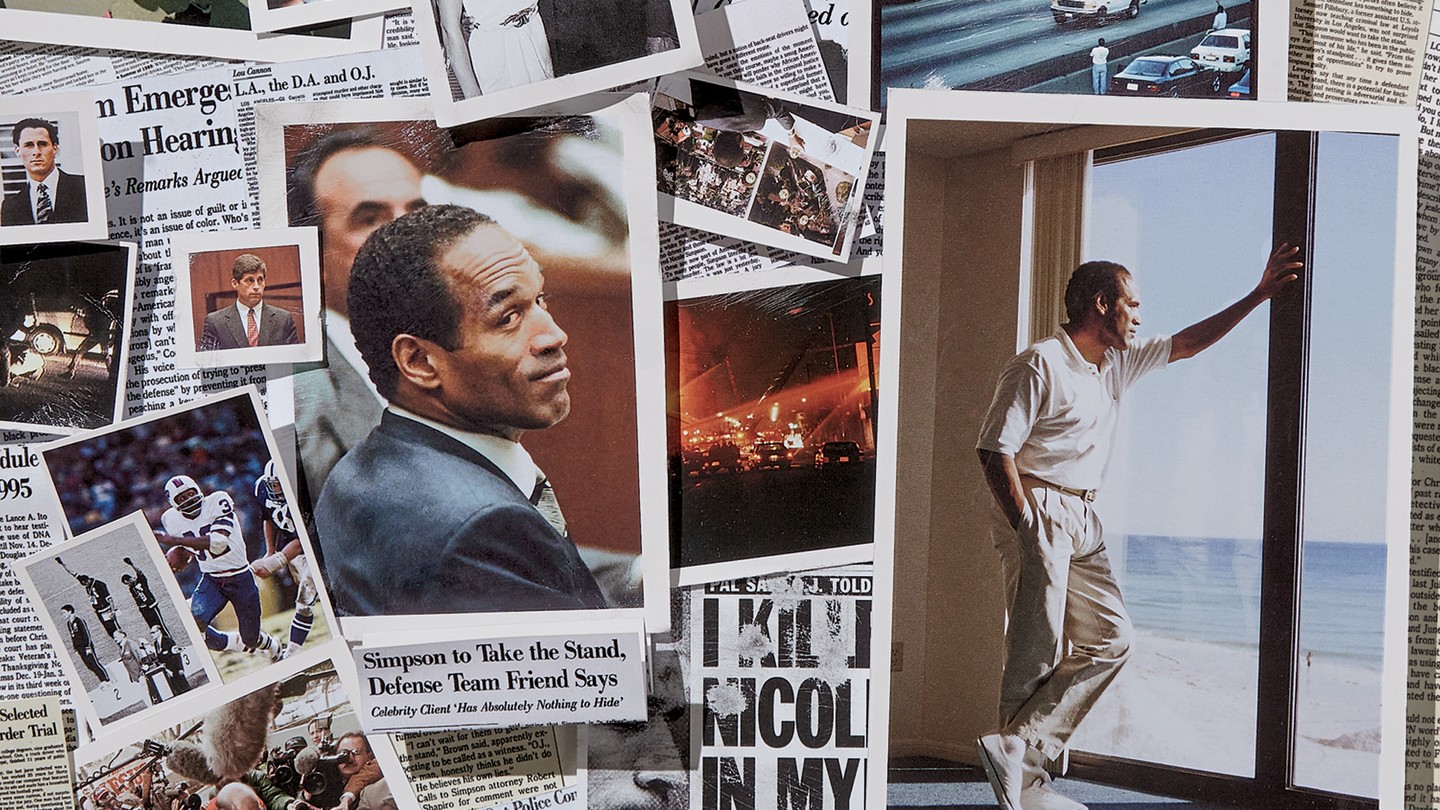

* Photo-collage images courtesy of Getty Images and Bettmann, Charles Steiner / Image Works, Focus on Sport, Jean-Marc Giboux, Lawrence Schiller, Lee Celano, Michael Ochs Archives, Mike Nelson, Myung Chun, Peter Turnley, Tiziana Sorge, and Vince Bucci