One of the biggest criticisms of NASA’s Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft is that they will be too expensive to fly. Namely—while the large rocket and sizable capsule appear to be more-than-capable vehicles that could form the core of a deep-space exploration program—will there be any money left after producing them for NASA to actually go and explore? Until now, this has been a question the space agency has offered only vague assurances about.

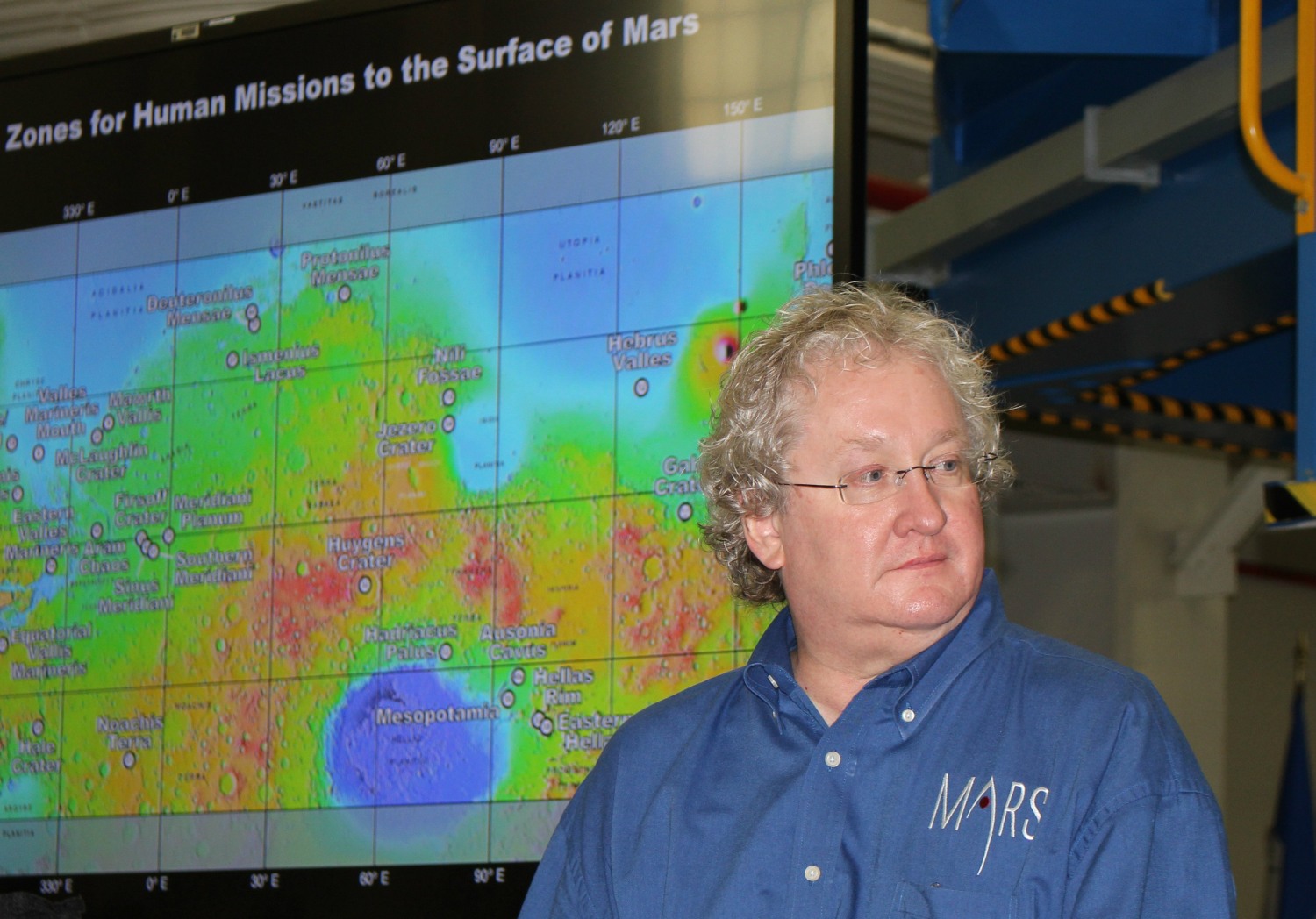

But on Thursday, when Ars sat down to interview NASA’s Bill Hill inside the Michoud Assembly Facility, where the SLS core stage and Orion are assembled, the NASA manager was notably forthcoming. “We’re just way too expensive today,” Hill acknowledged. “It’s going to take some different thinking and maybe a little bit more risk taking than what we’re wanting to do today.”

Hill should know. As deputy associate administrator for exploration systems development, he is the NASA headquarters official responsible for the development of SLS, Orion, and the ground systems at Kennedy Space Center. Hill said he has given managers of each of those three programs some targets for production and operating costs once the vehicles move out of the development phase and into production.

Top number

“My top number for Orion, SLS, and the ground systems that support it is $2 billion or less,” Hill told Ars. “I mean that’s my real ultimate goal. We were running at about three-plus, 3.6 billion [dollars] during the latter days of space shuttle. Of course, there again, we were flying six or seven missions. I think we’re actually going to have to get to less than that.”

Loading comments...

Loading comments...