The long wait, filled with anxiety, is at last over. Very early on Tuesday morning, I was woken up by another alarming ring on my phone; it is part of the routine these days as the ordeal continues for journalists in Turkey. It was a text message from the doorman of my apartment block in Istanbul. “Mr Yavuz, police entered your flat a short while ago with the help of a locksmith. They did not damage or take anything during the search. Told us about an arrest warrant for you.”

Slightly relieved that at least the raid had been conducted in the correct fashion, I called my wife, who was at the Aegean coast, and had just woken up. One can imagine how shocked she was about this intrusion into our privacy. I wasn’t. I’m fully aware that a consequence of the botched coup is the nullifying of whatever remains of dignified journalism in Turkey.

Having seen the targeting of 72 year old Şahin Alpay (one of Turkey’s most powerful, dignified, consistent liberal columnists) and Lale Kemal (a veteran reporter, known for her stories for Jane’s Defence Weekly, sent to jail for their independent professional stands) I knew one day it would be my turn.

In the days preceding this clampdown, there were clear signs of a brutal escalation of the attacks on our freedom and diversity. After the recent closure of pro-Kurdish newspaper Özgür Gündem and the arrests of intellectuals such as author Aslı Erdoğan, police raided another Kurdish paper, Azadiya Welat, in Diyarbakır, and rounded up 27 Kurdish staff. In addition, 36 workers at the state broadcaster TRT were detained and sent to jail.

We had begun the week with immense pressure on us, sending private messages to each other in the industry: “Just be careful.” What else could we do, vulnerable as we are and abandoned by European politicians?

I learned on Tuesday morning that Murat Aksoy was among those arrested. Murat, a commentator in print and TV with social democrat leanings – who has never hidden his Alevi roots – is not only a journalist, but also had recently been recruited as press adviser to CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu. In those same early morning hours I learned that the house of Ali Yurttagül, not far from where I live by Bosporus, had also been raided. Ali was a columnist, like myself, with the English language Today’s Zaman, until it was brutally seized and shut last spring. He has been a respected adviser – as a member of the Dutch Green movement – to the European parliament on Turkish affairs for decades.

Soon I read the news story of a fresh roundup: 35 journalists were being hunted that day. A new list of “public enemies” was issued. It included my name. By Tuesday night, we knew that at least nine of those on the list had been taken into custody, which means up to 30 days under arbitrary confinement, according to emergency regulations. Why was all this happening?

That evening, all efforts with my lawyer shed no light on what was going on. I still have no idea, at the time of writing this, what I am accused of – because, as my lawyer told me: “All the files in this sweep are classified.”

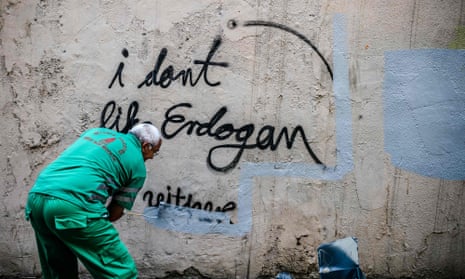

It may look like a puzzle to the reader, but we all know by now what this destructive pattern of targeting journalist means, it has been clear since as early as the Gezi park protests. The logic of the clampdown is plain and straightforward. The Turkish government, ruled strictly by President Erdoğan, is keen to fill the agenda with what it sees as “domestic enemies”, called terrorists. Large chunks of the Turkish media have therefore been branded as such, just because it is seen as affiliated to the Gülen movement, and almost the entirety of the Kurdish media is seen as serving the interests of the PKK.

It is not about what you report or comment on, it is all about which media organisation you work with. As long as you are critical and inquisitive about Erdoğan’s policies, you are persona non grata. You may only get fired, but if you insist on an independent journalism, the path leads to court or arrest.

As of last Saturday, the Platform for Independent Journalism (P24) had reported that 108 colleagues were in jail. Now, with the latest roundups, that figure is sure to rise above 150.

It goes without saying that the leaders of the ruling AKP top the league as the enemies of journalism – far higher than several dictatorships combined. Yet many in the west seem to believe that this ordeal is part of the “democracy celebrations” in the wake of the bloody coup attempt.

I am left speechless. Numb. And, very, very bitter that I am forced to a self-exile, in Europe, torn away from my crying, beloved country.