There is music you grow up with, and then there are the bands that grow up with you. Some of these bands have known each other since childhood, going through playground scraps, exams, fleapit rehearsals then flashy studios side-by-side. Then there are those who came together as they shaped their early adulthoods in music venues and indie clubs, clusters of like-minded souls that now live separate lives. Despite the years that have passed, they return to each other, making music that tells us who they are.

For fans, these occasional visits feel like homecomings, connecting them – connecting us – with special moments in our lives. I’m like this with Teenage Fanclub. Every time I hear their bright, ringing guitars, those longing, sun-hazy oh yeahs, it’s 1993, and Norman 3 is soundtracking my 15-year-old unrequited love life; or 1995, and Verisimilitude has me kissing boys and dreaming of brighter horizons; it’s 1997, and I Don’t Want Control of You is my first great relationship, soaring to the stars; or it’s 2003 and I’m writing my first piece of music journalism, about their brilliant greatest hits Four Thousand Seven Hundred and Sixty-Six Seconds, marvelling at the effect they have on me and other people.

This autumn, Teenage Fanclub – aka Fanclub, the Fannies or TFC to their legions of loyal fans – release their 10th album, their first for six years, called Here. A record already hailed in early reviews (“[it] brims with a staunchly good-hearted, quietly emotional desire to communicate something true,” says Uncut), it comes after 27 years of them being considered British rock’s unluckiest nearly-men – the friends of Nirvana who had huge critical acclaim in America in the early 90s but missed out on mainstream success; the makers of some of the best records of the Britpop era with only a handful of significant chart positions (1995’s Grand Prix made No 7, 1997’s Songs from Northern Britain, No 3).

Here’s title is plain-speaking and wistful, and also suggests a sense of permanence about place. But the band hasn’t had anything like that for years. It was named by a Canadian (Norman Blake’s wife of 20 years, Krista, with whom he has lived in Ontario since 2009), begun in rural Provence, mixed in Hamburg, and finished in Glasgow, where the band’s story began nearly three decades ago.

Here doesn’t divert from TFC’s long-established style, but what style it is: mid-paced guitar-pop taken somewhere divine. It has wide-eyed, wonder-seeking melodies, lyrics that roll in bliss or bruise with their tenderness, and pitch-perfect, west coast-influenced harmonies from its three singer-songwriters, Norman Blake, Gerry Love and Raymond McGinley.

The trio play today alongside drummer Francis Macdonald and keyboardist Dave McGowan, but they have shared writing duties equally since their highest-charting album, 1997’s Songs from Northern Britain (this is the fifth record in a row where each of them has four songs apiece). But while they have always hovered around melancholy, Here’s lyrics appear darker and sadder, seemingly about the gnawing desire to escape, about desperation in life’s toughest moments. It is about TFC getting on and growing older, and trying to make sense of that in song.

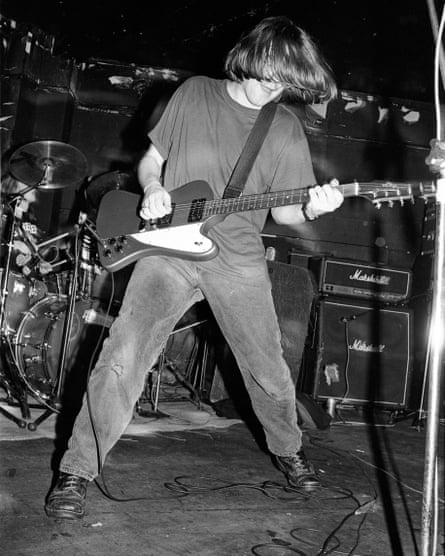

Glasgow’s Trans Europe Café, August 2016. A huge, detailed map of the continent stretches over one wall, and Raymond McGinley apologises for staring at it. “Where’s that by your shoulder?” He adjusts his sharp, black-framed glasses, his white crop a far cry from the altercation-with-undergrowth-mop of the band’s early years. “I went there, to Syria, after we toured once. Homs was really beautiful, and Aleppo…” He gets lost in a reverie. “Although most of the city was closed off when we were trying to get in, because Assad was opening a hotel.”

When devout indie kids think of Teenage Fanclub, they often think of Scotland’s second city. They think how the band emerged from Glasgow’s 1980s DIY-inspired scene, initially driven by Orange Juice and Postcard Records, then the Splash One indie club run by Primal Scream’s Bobby Gillespie (Blake and McGinley met here in 1986; Stephen Pastel of the Pastels put out the one and only 12-inch by their first band, the Boy Hairdressers, a year later – the unfortunately titled ode to the sun, Golden Shower).

TFC took that independent-minded legacy further when they formed in 1989, recruiting Love at a Dinosaur Jr gig. They never looked to fit in with any general scene: in their sound as well as their attitude, they’ve always been a band looking out, not looking in. “Glasgow transcends Scotland, really,” explains McGinley, a chicken panini, salad and crisps arriving in front of him. “Good cities always do – they’re not about nationalism. They’re about becoming a little centre of the universe.”

McGinley was born in Maryhill, north Glasgow, in 1964, and has lived in Pollokshields to the south since 1992. His father did many jobs, he explains – demolition worker, bus driver, cigarette-machine fixer – while his mother was a school cleaner, made redundant in 1990 when the service was privatised. Her redundancy money played a vital part in TFC history, though, as it helped fund a trip to America that same year, when they were just breaking through. (She’s 78 now, and loyally attends homecoming gigs.)

McGinley was also the band’s de facto manager from day one, negotiating early deals with British label Paperhouse and Matador in the US, before bigger guns – Alan McGee’s Creation in the UK, and Geffen in the US – came on board for 1991’s career-defining Bandwagonesque, their third LP. The yellow moneybag on its cover, on an acid-pink background, says a lot about their sly humour. “I remember still living in the council flat with my mum and dad at that time,” McGinley remembers. “Four floors up, talking to our New York lawyer on the phone, him wanting to send me a fax, and me saying we didn’t have a fax, him expecting me to go out and buy one.” He laughs, gently. “He didn’t realise we didn’t have any money.”

McGinley is the band’s introvert, famously restrained up on stage, but when he talks about the music that shaped his childhood, he can’t stop – and the roots of the romance of Teenage Fanclub bud here. There was the friend of his father who lent him records by Doris Day and Tommy Steele when he was eight (“I couldn’t believe his headphones! I’d be sitting in the corner of the room listening again and again while my family watched television”) and the towerblock landing where a friend’s brother would sell him albums as a teenager (“we wouldn’t go in, though – that felt too intrusive”). Everyone liked Pink Floyd back then, he says, but not the Syd Barrett era, which McGinley found odd. “I never got that there was music you shouldn’t like. The Syd records made me feel something, so I kept listening to him.”

Music’s ability to stir up feelings inspired his songwriting later, McGinley admits – and this lies at the heart of Teenage Fanclub’s power as a whole band. “It’s not that you should write for other people – you really shouldn’t, you should write for yourself – but you are definitely trying to affect something in other people when you write.”

From their first single, 1990’s Everything Flows, TFC were dealing in the shared emotional acknowledgement of the passing of time (“You get older every year/ But you don’t change/ Or I don’t notice you’re changing”). By their breakthrough single, 1991’s The Concept, they were creating fully-formed relatable characters (“She wears denim wherever she goes…”) that we love, then we lose (“I didn’t want to hurt you… oh yeah”). Decades later, that song was used prominently in Jason Reitman and Diablo Cody’s 2011 indie film Young Adult, Charlize Theron singing along to it as she drives out into the world, into sunshine, and into her history in the opening credits. TFC’s songs are full of the emotional resonance of that journey between adolescence and adulthood – and then its memory, still sparkling on some distant horizon.

There’s an extra element of underdog emotion in the Teenage Fanclub narrative, that idea that they’ve never had the mainstream success many believe they deserve. (“Although as a bit of received wisdom, it’s not a bad one to have,” McGinley smiles.)

The details of this are impressive. Bandwagonesque beat REM’s Out of Time and My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless to become Spin Magazine’s No 1 album of 1991 (they still play in the US off the back of that 25-year-old record, McGinley says, although it only had minimal commercial success over there).

They were Alan McGee’s favourite band on Creation when Oasis were huge, with even Liam Gallagher proclaiming that they were the world’s second-best band behind, oh, wait, yes, his own. Their album Grand Prix (1995) still plays like a collection of huge, radio-polished singles as well, although it only poked its nose into the top 10 for a week.

In a 1991 NME interview, McGinley enthused about TFC playing huge gigs (“we quite fancy playing stadiums”), but that comment wasn’t about being famous, he stresses today. “A gig is something of substance – that’s 2,000 people enjoying your music. When people say, ‘Oh, stadium gigs are terrible…’” He shakes his head. “They’re the dream. It’s all the other bullshit that’s rubbish – the videos, the campaign strategy.”

This is something Love agrees with when we meet him across town half an hour later. TFC’s apparent failures were the making of them, he says, and the reason why they still succeed as a band.

December 1993, San Francisco. Tony Bennett is on stage, singing his signature song about leaving his heart in the city. People in the audience are welling up, weeping, sobbing. The legend bows, and he exits – then Teenage Fanclub walk on stage carrying mandolas. Everyone boos.

“It was this thing called Acoustic Christmas – and we took it literally,” Love says, laughing. He is a sweet soul, the pale blue eyes that made him TFC’s closest thing to a heartthrob still piercingly pretty. “The day Tony Bennett supported us,” McGinley sighs. “He was very gracious,” Love adds. Both talk happily about their brushes with bigger stars. TFC were friends with Nirvana before the latter got huge; they would wash their smalls at Krist Novoselic’s house when they played in Seattle, and both fondly remember hanging out with Novoselic and Dave Grohl one afternoon in Sweden: “I remember Dave insisted we go to the Hard Rock Café to look at some Abba memorabilia,” Love beams.

Grohl also asked TFC to support the Foo Fighters in Manchester last summer, which they did – they were very touched. “But most of [the crowd] that night were staring at us, confused,” says McGinley. “That brings you back down a bit.”

TFC settled into being a support band rather happily in the 90s, though, Love bounces back. They supported Radiohead in the US in 1997, when OK Computer was colossal; both bands hit it off, and got obsessed with playing golf, finding courses around every venue. “When you’re a support band, you can have a holiday,” Love says delightedly.

Music transported Love in other ways throughout his life. The third of eight children, his early memories include the family piano being taken away by the council, and the music of the Everly Brothers playing through his small house (“those harmonies still influence my songs”). He was born the same year that the huge Ravenscraig steel plant opened in Motherwell, to Glasgow’s south-east. He lived in its shadows, and you see images of it juxtaposed with sunny American beaches in the video to Ain’t That Enough, which became TFC’s biggest hit to date in 1997. Ravenscraig had been closed down in 1992, and its huge cooling towers were blown up in 1996. “Here is a sunrise,” went the beautiful chorus, “Ain’t that enough?”

Those towers would also appear on the cover of their 2003 greatest hits album, Four Thousand Seven Hundred and Sixty-Six Seconds, Blake, Love and McGinley standing on a wide, sandy beach looking at a picture of them. Love is warmly reflective about those times. “We don’t travel as far as we think we do from the music we like as children, really, do we? I still like to keep in touch with the wee guy I was who wrote my first songs.”

Love’s also had a solo project in recent years, under the name Lightships; 2012’s Electric Cables was a beautiful, forever-young album. (McGinley and Blake have embarked on collaborations, the former playing with Glasgow folk-rock band Snowgoose, the latter forming a duo with US indie musician, Joe Pernice, The New Mendicants; still, they are not “getting back together as Teenage Fanclub to make money”, McGinley insists. “If we did that, we’d be meeting up every 18 months.”)

Today, he’s content to wander around Hyndland in Glasgow’s West End, where he lives with his Spanish partner, and just get on with things, though. “I’m just happy to just go down to Morrison’s and see what’s on the fish counter. I am! I’m nearly 50! That’s my excitement these days.”

Teenage Fanclub’s late-period albums have all had their sombre moments: songs that cut you to the quick such as If I Never See You Again (from 2000’s Howdy) – “we’ve only got a lifetime”, it sighs, Fallen Leaves (from 2005’s lovely Man-Made), and Dark Clouds (Shadows, 2010). But Here feels even more plaintive and sad, and occasionally crackles with anger. When McGinley writes, “I don’t hear much fanfare for the common man these days,” on one of his tracks, I Was Beautiful When I Was Alive, he’s commenting on how seemingly liberal people easily deride those less lucky than them (“when people call others ‘neds’… I just think, hey, that was me 30 years ago,” he says). Blake’s songs feel even blacker. “You’ve been dark as a knife, out of luck, out of life,” goes Live in the Moment. “There is pain in this world/ I can see it in your eyes/ And it’s so hard to stay alive/ At the edge of the night,” goes the otherwise chirpy I’m in Love.

Blake remains relentlessly chirpy in person, however, as he has always been in his band, speaking on the phone on a sweltering afternoon from Kitchener, Ontario. We go over territory discussed with his bandmates and he’s soon gushing away: the son of two newsagents brought up in Belshill, south of Glasgow, he grew up happy because he could read comics, he says (“like the Dandy and the Beano – and Bunty, of course – they were all free!”). He also remembers key people from the 80s Scottish indie scene with obvious tenderness. “I saw Bobby [Gillespie] on his bike in Primrose Hill a few years back, and stopped him – it was brilliant. I still remember him really young, with his haircut, and his bag, in little record shops in town, like it was yesterday.”

He also remembers fondly Teenage Fanclub’s high times in the 90s. He tells a story about being drunk backstage with Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood and Marilyn Manson: “And I’m all throwing my arm around old Marilyn: ‘Haway there, big man! Haway, big fella!’ Then he said to Jonny, ‘What are you doing tomorrow? There’s this great little place I know in the village for dinner.’ I thought it was hilarious! A great little place for dinner! Marilyn Manson!”

He acknowledges that there is a sadder, darker strain to TFC now – but believes it’s always been there. “I think Scottishness might be a part of it – those ballads and laments and airs that were around when we were kids.” Age also has its effects on their writing, he says. “Our guitar tech’s 65, and he keeps saying how invisible you become to younger people as you get older, and he’s right. Plus you experience death more, and illness. And you just don’t do things you did when you were a young rock’n’roller.”

He checks himself for a moment. “I guess not if you’re Mick Jagger, though. He’s having a baby, isn’t he? Bloody hell.” Broad laughter. “I guess because the Stones were famous at 20, they’re still acting like they’re 20. We were never famous, so we’re still getting old.”

Fatherhood has also influenced Blake, as the only dad in the band; his daughter Rowan is 20 now, about to return to Glasgow to attend university. She likes the Velvet Underground, and he saw the band Alvvays with her recently, which he found fascinating. “The fact that bands of her age play music influenced by the early 1990s, and the times we were in…” He tails off. “But maybe it was the same for us, making music influenced by the mid-to-late 60s. Maybe that’s when our stories start in our heads. Or we long for those times when we first connected to those feelings.”

When Teenage Fanclub get back together, it always feels good, Blake admits. In a typical first hour together, they’ll talk for 40 minutes and play for 20, but then the music will take over. McGinley, Love and Blake will have brought songs ready in melody, but the lyrics will only become fully-formed when they are together, wherever they are. They’re “obviously influencing each other in that way, and needing each other in that way”, Blake says, plainly, but wistfully. Those words land, join and communicate, and a 27-year-old story carries on.

Teenage Fanclub are here, then, after all: in a certain breathtaking familiarity of feeling, in that moment between then and now. “It’s a place we can’t help coming back to,” Blake says, with obvious joy. “It’s the place we all know.”

Here is out on PeMa Records on Friday. The band plays London’s Islington Assembly Hall tomorrow, the Liquid Room, Edinburgh, 6 September, Gorilla, Manchester, 7 September, and tour the UK in November

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion