Safety Last! / Public Domain

Why Film has not been Disrupted Yet, Part 1

The film industry has resisted disruption so far. Either Big Media is bulletproof, or the real changes still lie ahead.

In 2012, tech accelerator Ycombinator issued one of its famous “Request For Startups”. It simply read: Kill Hollywood.

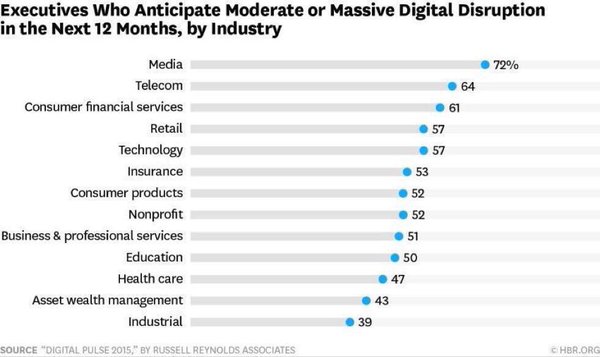

There has never been a shortage of soothsayers predicting Hollywood’s imminent demise. Media and filmed entertainment are perpetually “next” on the software-eating menu. But for all of the gametalk, nobody seems to be moving that media disruption needle just yet.

The early 21st century has witnessed deep and secular changes to many major industries. Eric Schmidt’s How Google Works is a victory lap among other things, but it is remarkable for one of its subtler thematic threads—one that was perfectly summed up by Esko Kilpi when he wrote that “The Internet is nothing less than an extinction-level event for the traditional firm.”

Uber is taking on transportation and logistics. AirBnB is upending the hospitality business. And Facebook has the entire publishing industry quaking in its little space boots.

But last I looked, we were still name-checking the same handful of major players in film and television. We have yet to see any challenger make a serious run at the studio system. So either the film and media industries are bullet-proof, or we are just lagging a little behind other industries.

At the risk of giving away the ending: we’re just lagging behind a little. Like Blockbuster Video or Mike Campbell in The Sun Also Rises, you tend to go out of business very gradually, and then all at once:

Media groups cling to aging ad sales strategies like Blockbuster once clinged to bricks and mortar.

— web smith (@web) July 6, 2016

Which means that the tipping point, and the really interesting stuff, still lie ahead. That in mind, I’ll be laying out five reasons—some technical, and some cultural—why I think filmed entertainment has largely resisted disruption so far.

- Making a movie is still an all-or-nothing proposition.

- Film technologists are focusing on all the wrong areas.

- Filmmaking is (computationally) expensive.

- We are a deeply traditional, conservative, and sentimental lot.

- The film industry neutralizes its best and brightest.

- Postscript: There Are Always Two Revolutions

Any day now!

1. Making a movie is still an all-or-nothing proposition.

I starting writing this first entry with the pedestrian observation that “filmmaking costs a lot of money”. Even RocketJump’s Video Game High School—probably the purest expression of the “DV Rebel’s” ethos—needed hundreds of thousands of dollars to deliver solid production values. We’re still a way off from the promise of Camera Stylo or Francis Ford Coppola’s “Fat Little Girl From Nebraska“.

(Full Disclosure and Mandatory Plug: VGHS used Endcrawl. And they thanked all 10,003 IndieGoGo contributors by name.)

But the problem is not that that filmmaking is expensive. Making software is expensive, too. The problem is that filmmaking requires large, upfront capital outlays. This heavily favors companies that can afford to place large, expensive bets. In the indie film sphere, it tips the scales toward folks who have easier access to capital or who are buddies with HNWIs. If you don’t believe me, visit any major film festival.

Independent film isn't just white people eating cereal in bed. Subscribe to @brightideasmag: http://t.co/kA9xsZG3p8

— Seed&Spark (@seedandspark) February 27, 2015

Software devs, for all of their many cranky disagreements, are more or less unanimous that the Waterfall Model is the worst possible way to go about creating anything. Yet Waterfall is precisely how we’ve been producing films for over 100 years.

There have been scattered attempts to squeeze concepts like “Lean” and “Agile” into the film space. This is laudable. It also tends to meet with heavy resistance. In fact, one of the first times I proposed a similar idea, I was sarcastically asked, “So what does the ‘lean’ version of Game of Thrones look like?”

That’s a fantastic question—the sort that can tease out some tantalizing answers.

But the problem isn’t that concepts like uppercase-A Agile arrive with their own particular baggage, or that they don’t translate gracefully from software into media production. The problem is that filmmakers, by and large, aren’t asking the question.

Instead, we are still busy chasing production models whose failure modes will likely as not beggar us.

The very concept of “greenlighting” a movie speaks volumes about the binary nature of film production: you’re either going all-in, or you’re not making your film at all. Late-stage plug-pulling is extremely rare: once you cross that Greenlight Rubicon, it’s all sunk-cost fallacy from there on out. And you won’t know for a year or three whether you’re creating a work of unrivaled genius, or whether you’ve already sired an irredeemable artistic failure.

Ted Hope touched on this topic in a blog post entitled, “Staged Financing MUST Become Film Biz’s Immediate Goal.” I agree with Mr. Hope in principle: the film production world effectively lacks Sand Hill Road’s language of investing rounds: Angel, Seed, Series A/B/C, etc.

But in tech, those funding milestones are tied to a bevy of metrics like MAU (Monthly Average Users) or MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue). Traditional waterfall film production, on the other hand, doesn’t start small and iterate. Waterfall relies on massive, one-time. all-or-nothing bets. We don’t solicit feedback. We don’t Default To Open. We are all unrecognized artistic geniuses who must Hide It Under A Bushel, for years, with little to no economic or creative feedback along the way.

It’s difficult to see how an investor can make rational, informed choices within that production model. Hence all the “stupid money.”

This is holding us back.

Staged financing, “smart money,” and a sustainable investor class are important goals. But we have to reach a moment when we acknowledge that these goals are incompatible with traditional formats. To wit: staged financing doesn’t play well with the venerable Feature Film.

Jason Scott aka @textfiles provided some insight along these lines when he posited that film and Kickstarter are fundamentally incompatible. I recommend reading the whole thing, but my key takeaway is that feature films cannot be meaningfully chunked in the way that an album or a video game can. As the old spittoon bar joke goes: it’s all one piece.

Disrupting film will require filmmakers and visual storytellers to start actively, manically experimenting with other content formats. Call it Promethean Storytelling. We need to keep asking the question: What does a piece of disruptive content look like?

Hey, while you're here ...

We wanted you to know that The End Run is published by Endcrawl.com.

Endcrawl is that thing everybody uses to make their end credits. Productions like Moonlight, Hereditary, Tiger King, Hamilton—and 1,000s of others.

If you're a filmmaker with a funded project, you can request a demo project right here.

Every Camera Company is a Software Company Now

The film industry has resisted disruption so far. Either Big Media is bulletproof, or...