It seems as if the FOMC still doesn’t know what to make of itself. In June, the May payroll report released earlier that month clearly spooked them; not even Esther George bothered to dissent in favor a rate increase. Since then, the world seems so much better. The media tells us with every new economic release how “strong” the economy has become. And they won’t let us forget that stocks are at, or are near, all-time highs.

These are all part of what policymakers told us in late 2014 would happen. At that time, the labor market statistics were more than suggesting “full employment” to economists, which meant so many good things that it would be up to the Fed to lightly spoil the fun. Then 2015 happened, catching central banks unaware and leaving them as equally unprepared spectators.

Despite the great run of late nobody expects the FOMC to do anything when it meets this week, betraying the 2014 narrative.

Since the policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee last gathered six weeks ago, economic reports have shown one example of U.S. resilience after another following a slow first quarter. When the monetary policy panel meets on Tuesday and Wednesday, a majority of investors expect them to do what they have done at every meeting this year: nothing.

This reluctance is, apparently, very hard to explain. It would be that way from a 2014 outlook that many still aren’t aware has been overrun. But, like the bond market “riddle”, the problem isn’t so much logic as perspective. The FOMC isn’t really sure why they aren’t really sure.

The strategy is aimed at nursing the economy through the uncertainties of various global shocks while puzzling over head-scratchers that include low productivity and how much support is Fed policy really providing to growth. At the same time, it can seem a highly discretionary, less systematic approach that puts a lot of weight on possible risks that are hard to define or just fade away.

To my view, that has been the central focus of markets since the middle of last year. There was always a persistent if vague notion that the Fed and other central banks were flying by the seats of their individual pants, but they were given the benefit of the doubt because of the lingering legend of Greenspan and the collective not wanting to face up to Bernanke’s only instance of successful inflation (of his reputation and actions) for fear it might discredit everything. Again, that was 2015; it made it painfully obvious to where only the most ideologically committed would refuse to recognize they have no idea what they are doing. Indeed, central bankers now have a difficult if not impossible task of even defining and reconciling what they have done.

The confusion and policy disorder, dare I write desperation, is palpable. Economists have spent years, really the whole span of this “recovery”, redefining the concept of recovery. They have constantly written down the standards by which any economy would qualify as acceptable. Did they really think there would be no consequences for leaving only a rump economy as the fulfilled end of QE?

Even those that do see it still don’t seem to get why. Last week I wrote about Brad DeLong’s quite right categorization of this “recovery” as the “Lesser Depression.” Larry Summers, a friend and colleague of DeLong, has spoken about and argued for “secular stagnation.” Even Paul Krugman has his mysterious “deflationary vortex.” These are all the same thing, with each described from a slightly different vantage point. None of them want to put all the pieces together because if put together into a comprehensive whole it would be the end of orthodox economics; a bridge way too far for any orthodox economist.

Krugman’s somewhat evolution is constructive in identifying this reluctance, especially as it relates to the “rising dollar” portion of the “recovery.” In September 2014, he brought up the “deflationary vortex” but only as a criticism of, and applicable to, Europe. In his view, the Fed did QE and the ECB did not (setting aside, apparently, ~€1 trillion in LTRO’s that were somehow different than QE).

And there but for the grace of Bernanke go we. Things in the United States are far from O.K., but we seem (at least for now) to have steered clear of the kind of trap facing Europe. Why? One answer is that the Federal Reserve started doing the right thing years ago, buying trillions of dollars’ worth of bonds in order to avoid the situation its European counterpart now faces.

Just a few months later, the “deflationary vortex” was suddenly global, if not yet, we are supposed to infer, American.

And you should feel a shiver of fear, even if you don’t have any direct financial stake in the value of the franc. For Switzerland’s monetary travails illustrate in miniature just how hard it is to fight the deflationary vortex now dragging down much of the world economy.

In March 2016, he finally admits just the possibility of the eurodollar as a monetary system; though he never, likely would never, identify it properly. The most that he could manage was to observe what so many have known all along, “that the linkages among major economies are strong. They are stronger than much conventional economic discussion suggests, largely I would argue because of capital flows.” Because of this open violation of the orthodox closed system approach, the “deflationary vortex” was a global problem openly thwarting monetary policy everywhere it was being tried. He even came close to recognizing the eurodollar as the central focal point by again confessing there is some potential that economists have been all wrong:

The interdependence of the major economies is, I will argue, very large. Ordinarily, the view that I and others have is that the interdependency is limited because even now international trade flows are not that big.

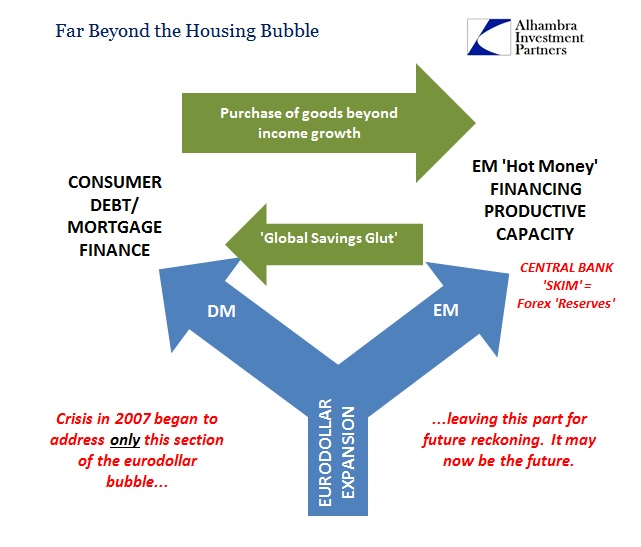

Trade flows are a distraction, but one that captures so much attention and ideology; the eurodollar knows no boundaries in terms of geography as well as function. The system’s grand buildup in the 1990’s and 2000’s fed in “both” directions; the housing bubble that we know well in the US and of the 2008 panic; but also the flow of “capital” into EM’s as the financing of productive capacity that was, in general, built on the assumption that the eurodollar would grow exponentially forever on “each” side. It was almost as if it was all expected to be the economic equivalent of the perpetual motion machine, a geometric extrapolation of growth to infinity and beyond (apologies to Buzz).

It all looks and sounds so familiar, but to economists it just can’t be. They learned their lessons from 1929 so there is no way they could be repeating them, right? Bernanke’s entire message was that because of his monetary “courage” 2009 never became 1929. That is, however, looking in the wrong place. The real problem is not the crash but what has followed.

Stay In Touch