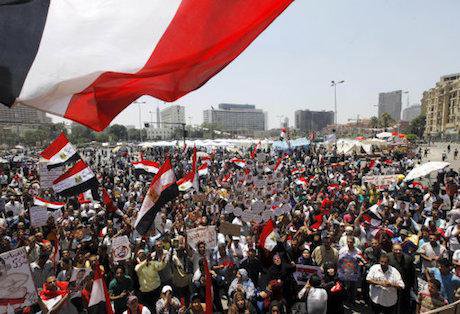

Martin Meissner/AP/Press Association Images. All rights reserved.Hazem Kandil, a political sociologist, was among the first to speculate that Morsi would not complete his term. The key to his impressive foresight lay in his assessment of what at the time was an obscure Muslim Brotherhood problem.

The problem, he asserts, lay in the Muslim Brotherhood’s misrecognition of the ‘revolutionary time’ in which their term was embedded. In a later book he further expatiated on how the Muslim Brotherhood mistook their long-awaited moment of rise (through Islamist reform) for the moment in which they actually rose to power in Egypt (through a revolution). ‘Moment’ here being key.

However, what explains their defeat is the patience of their rivals, the security state, in recognising ‘the moment’. As Kandil highlighted:

“Part of the reason Egypt’s security establishment has landed on its feet is that it has been careful to bide its time. It seems willing to refrain from full-blown ‘pacification’ until the revolutionaries come to learn that the only alternative to police repression is chaos.”

An equally brilliant political sociologist, Simon Waldman, explained the recent failed coup in Ankara on similar, but opposite, lines. In Turkey, Waldman avers, it was the coup forces that failed to recognise the moment.

On the other hand, not only was Erdogan’s party prudent in dealing with the moment, but even their civil opposition (who unanimously condemned the coup), including those who had been continuously calling for the impeachment of Erdogan, recognised that it was not the appropriate moment.

Did Egyptians fail to 'recognise' what they saw in 2013?

Why did the Turks recognise what the Egyptians could not? One line of argument spoke of the ‘level of education’, which is of course skewed to the Turkish side. This argument however fails to explain how and why Egyptians led a massive uprising in 2011.

Another line highlights the variation in the degrees of military discipline. A third even highlights the degree of the Turkish public’s discipline in fighting against back the coup – more or less the Erdogan/democracy supporters.

The three arguments, and plenty of others, highlight important structural factors which make Turkey more coup-proof than Egypt. In retrospect, any of the above factors make sense. But it is interesting that these arguments did not come about except after the reinstallation of Erdogan’s regime. I wonder if these factors would have made any sense if the coup had actually succeeded.

Imagining the ‘counter-factuals’, brings a key analytic problem to the fore in dealing with such great events as coups and revolutions. As Didier Bigo highlights, the scholars have a, “tendency to explain great events […] [in terms of] great causes”.

Not that structural factors do not play a role in framing the conditions of particular opportunities (and, in turn, defying other openings). Yet, minor details, mundane practices, instinctive cognitions and even chances and coincidences decide which of the variant possibilities is realised.

That being said, it is disingenuous to assert that particular ‘structural’ factors, like education, economy or discipline, make one nation ipso facto coup-proof and another coup-prone. As recent events in Turkey taught us, a coup is a bet that always stands both chances of failure and success (not with equal weights, but with simultaneous possibility).

Acknowledging the above does not answer the question: why could the Turks recognise what the Egyptians could not? It rather complicates it.

It shows the multiple dimensionality of the two situations, which problematises the question’s assumption of a singular narrative that asserts ipso facto that the Turks’ position was intelligently superior to that of the Egyptians.

The narrative may make sense, at this particular moment, given the atrocious situation in post-coup Egypt. But we do not know whether Erdogan’s comeback will not lead to similar atrocities. We also have no way of knowing the counter-factuals in both the Egyptian (if Sisi’s coup failed) and Turkish (if Öztürk’s coup was realised) cases.

On what basis, then, do we decide that one position was a ‘misrecognition’ while the other an ‘appropriate recognition’ of the historical moment?

It is probably what we have been continuously hearing from International Relations professors in the last few decades: don’t play with coups, coups are naughty! But probably these ‘grand’ professors, or at least the ancient founders of the discipline, thought of coups in an entirely different way. For in their time, coups were the main conventional possibility for an effective political change (think of Machievelli’s Prince). But in our (modern, “democratic”) time, things are quite different. Time here is key.

Time as an active agent

Time in politics is more complicated than ‘clock’ time. The latter is an unconscious, linear, irreversible continuum that moves at a constant pace independent of the events it passively contains. An hour in your wedding is physically equivalent to an hour at your bestfriend’s funeral. The clock does not understand, nor account for, the first passing in a glimpse with the second passing in years. But humans do understand the difference.

Thus, political time is a subjective social construction – in which both the ‘moment’ (which frames the event) and the ‘event’ (which defines the moment) mutually-construct one another. Neither has a meaningful existence independent from the other.

The multiplicity of events and histories through which the moment/event singularity come to the scene, leaves us with no ‘one’ right answer of what the moment is, but rather plenty of possible understandings of the historical moment and the possibilities immanent in it – many co-existing ‘presents’.

The events of 25 January 2011 were defined through the scope of the ‘Arab Spring’, and it was through these events that this ‘time’ was defined and constructed. To list some of the understandings of January 2011: a moment of upsurge, revolution, chaos, and coup (in the sense that the military was the institution which effectively removed and replaced Mubarak). But its conceptualisation as an extension of the period of the ongoing Arab Spring made the revolutionary component more vivid and vibrant.

The period between June – August 2013 was a bit more controversial. Having followed the earlier revolution, the events were read by many as a ‘second revolution’ or an ‘extension of January’. This allowed many to see beyond the ‘coup’ fact - which was not less obvious.

At least three assumptions about time were pertinent in such understanding:

First, the assumption that we are in a revolutionary time. Tamarod’s sign-up sheet is a vivid depiction of such revolutionary-consciousness. All the reasons for rebellion stated by Tamarod revolved around Morsi’s failure or reluctance to meet the demands of January’s revolution.

They concluded that “the ordinary citizen feels that not a single goal of the revolution was met […] I hereby sign to withdraw confidence from President Mohamed Morsi.”

Such evaluation of revolutionary progress was not in vain. It came through comparison with other revolutionary cases such as the Iranian revolution or French revolution. The first gave the possibility of an Islamist twist of the revolutionary movement, while the second demonstrated that revolutions take place through multiple phases (in which the July coup/revolution was taken as a second phase).

Understanding the Egyptian revolution in terms of the French allowed for another implicit assumption: progress. There was a feeling of: if the first was overthrown then the second can be as well. It’s difficult to decipher where the notion ‘the more presidents we overthrow the merrier’ came from. But it was definitely there and evident in the popular chant (highlighted by Maha Abdelrahman) “W-Lessa [not yet still]”; which implicitly assumes a forward moving continuum.

Third, a revolutionary time is an exceptional time. This general feeling of ‘exceptionality’ explained to its beholders a plethora of paradoxical unconventionalities that defined the coup moment. One of which is the participation of army and police officers in demonstrations, which is not only against their constitutional obligations but also against Egyptian (or universal?) common-sense.

I remember a friend asking me a question on that day – if the police-force is with us, who are we fighting? The extreme ease of this so-called revolution should have been puzzling to most Egyptians, but it wasn’t. It was normal in exceptional times.

Even the massacre of thousands at Rabaa and Nahda a month later was not given its due attention; for again, the exceptional circumstance permitted exceptional measures. When the temporal mode of exceptionality becomes the norm, as Giorgio Agamben has stated, nothing becomes exceptional.

'People' or 'time' - who is to blame?

My extremely limited expertise in Turkish affairs thwarts my aspiration to complete this Egypt/Turkey comparison. But does it need much expertise to observe that the perception of a revolutionary moment was more vibrant in Egypt 2013 than in Turkey 2016? Does it require much expertise regarding Turkish history to understand how the Turks’ cumulative experience of coups makes ‘coup moments’ less exceptional to them? Doesn’t it make sense for the atrocities of the Egyptian coup to serve as alarm bells for any coup attempt in the region? I leave these questions for Simon Waldman, Hazem Kandil and other specialists to respond to.

Amr Nabil/AP/Press Association Images. All rights reserved.The argument which I wish to make, however, is that it isn’t the capability of recognizing a historical moment that renders the contrast between the Turkish trajectory and the Egyptian. It is rather the historical moment itself, and the political construction of what this ‘moment’ resembles in society’s consciousness. I make this argument in the hopes it allays the self-recrimination of the Egyptian people.

Maybe if the Turkish coup had come first, things would have been different. Time, like people, has its own political agency. So at least give the ‘time’ of June-August 2013 in Egypt a share of the blame currently placed on the shoulders of the Egyptian people.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.