Here’s a question for both supporters and critics of the Black Lives Matter movement:

What does Black Lives Matter want?

Not sure? How about this. Can you cite a moment in which a BLM leader passionately and eloquently denounced the recent shooting deaths of eight police officers in Dallas and Baton Rouge? Can you name one or two leaders from the movement?

Chances are the answers to those questions fall all over the place. Four years after its founding, BLM is still a movement without a clear meaning for many Americans. Some see it has a hate group; others as cutting-edge activism and yet others as just a step above a mob.

“Most of the folks in the movement are young and we’re black so they assume we’re uneducated and uninformed and we’re just angry and in the streets,” says Johnetta Elzie, a leader in the BLM movement and Campaign Zero, another organization formed to fight police brutality.

Those assumptions may now get worse as BLM leaders confront a make-or-break moment that virtually all protest movements eventually face: What happens when your enemies and unexpected events do a better job of defining your movement than you do?

BLM leaders are under a new kind of scrutiny because of a whiplash of unexpected events: cell phone videos of two black men who died from police gunfire followed by the ambush and killings of five police officers in Dallas at a Black Lives Matter protest, and three police officers targeted and killed in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

As a result, activists and scholars say BLM is facing the same challenge that confronted striking steelworkers in the 19th century, gay activists blindsided by the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, and Occupy Wall Street demonstrators in 2011. These movements initially captured the public’s imagination, then their existence was threatened by something over which they had no control.

Some of these movements adjusted; others withered.

“The action is on page one; the retraction is on page 88,” says Jerald E. Podair, a historian and author of “Bayard Rustin: American Dreamer.” “If you cannot adapt you’re simply not going to survive.”

Can BLM adapt? The same organizing philosophy that has helped the movement grow may lead to its demise, some activists and historians say. They cite these four reasons:

Reason No. 1: The buck stops where?

BLM organizers made a bold decision when they organized as a hashtag on Twitter four years ago. It was going to be a “leaderful” organization; not one led by a single leader or a centralized leadership structure.

“We’ve always made it clear that we are one of many,” Elzie says. “There’s not one person who can be a leader of the movement. We’re all leaders.”

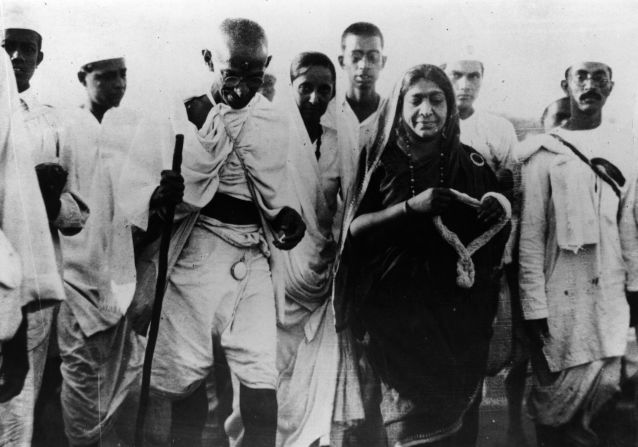

There’s a shrewd pragmatism to that decision. Movements built around charismatic leaders evaporate when that leader is assassinated or discredited. The civil rights movement never recovered from the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. Few today can name the organization that Malcolm X headed when he was assassinated by Nation of Islam members (It was called the Organization of Afro-American Unity).

The movement’s decentralized form of leadership, though, can hurt it when responding to a crisis. Who does the media go to when protesters invoking BLM burn a police car or chant “Pigs in the blanket?” Who speaks for what BLM wants when it has 37 chapters nationwide that list varying goals in their mission statements?

“When something tragic happens, we’re all blamed because there’s no central leadership,” Elzie says. “We all take a hit.”

The recent police shootings led critics to call BLM a hate group. The Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks hate groups, actually felt the need to release a report last week explaining why BLM is not a hate group.

BLM leaders took a step this week in defining their movement when they released a “Black Lives Matter Policy Agenda.” The agenda is the result of a collaboration among at least 50 groups, BLM leaders say.

The list of demands is sprawling, but the proposed policies include six central demands: “end the war on black people,” reparations, investing in the education and health of black people, economic justice, community control and political power.

Even if people eventually agree on what BLM wants, people still don’t know what it is.

In fact, there are at least two versions of BLM. There’s the BLM network founded four years ago by three black female activists angry over the death of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teen killed by a neighborhood watch volunteer while walking home. They created the #blacklivesmatter hashtag. Then there’s the BLM movement, a more amorphous collection of racial justice groups like Campaign Zero.

Elzie, for example, doesn’t call herself a BLM network leader. Her group is Campaign Zero, but she does consider herself a member of the BLM movement.

Yet there are advantages to decentralized leadership as well. Consider what BLM has accomplished in four years.

It has illuminated complex issues like mass incarceration and racial bias in policing for millions of white Americans. BLM activists helped vote out the state’s attorney for Cook County, Illinois, this year after it was revealed she waited over a year to file charges against a Chicago police officer who shot to death a black teen.

Hillary Clinton, the Democratic candidate, has already adopted some of BLM’s rhetoric, by talking about systemic racism and saying at one rally, “Yes, black lives matter.”

And President Obama has publicly supported the group at a recent town hall hosted by ABC.

“The phrase ‘Black Lives Matter’ simply refers to the notion that there’s a specific vulnerability for African-Americans that needs to be addressed,” Obama said at the town hall. “It’s not meant to suggest that other lives don’t matter; it’s to suggest that other folks aren’t experiencing this particular vulnerability.”

According to a Pew Research Center poll released last month – taken before the Dallas shootings – roughly 4 in 10 Americans support BLM. Still, a large number, 30%, said they have not heard anything or had no opinion about BLM. And about 40% of whites who have heard of BLM say they don’t understand its goals.

Great leaders eventually emerge in most protest movements, says Timothy Patrick McCarthy, an activist and Harvard history professor who studies protest movements.

“Martin Luther King wasn’t Martin when the movement began,” says McCarthy, author of “Protest Nation: Words That Inspired a Century of American Radicalism.” “We have yet to see perhaps a leader like King or Malcolm X or Ella Baker emerge. Maybe we have and we don’t just know it yet.”

Reason No. 2: They’re not trying to speak White America’s language

Here’s something else that’s striking about BLM: The movement is filled with passionate and eloquent speakers, but can anyone name a great speech or even a memorable soundbite by a BLM leader?

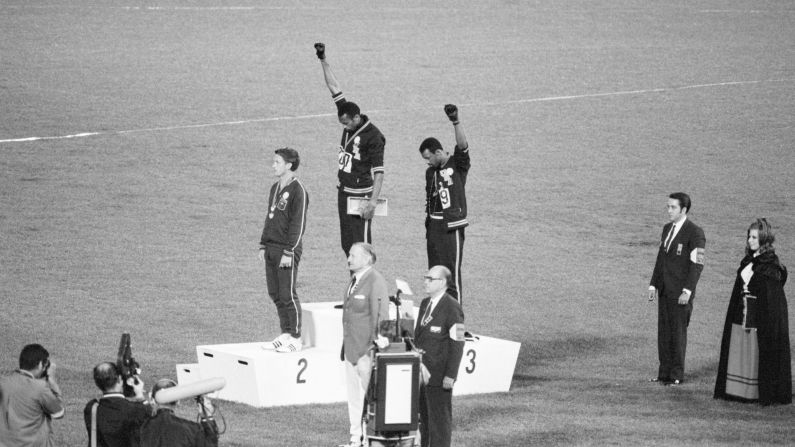

One speech and one image come to mind. The electrifying speech by actor and activist Jesse Williams defending BLM at the recent BET awards.

And the viral photo of Ieisha Evans, BLM marcher, facing off against a phalanx of riot police. She is armed with nothing but a look of serene resolve.

But there’s little sense yet that BLM has consistently come up with the type of reassuring language that has traditionally moved skeptical white Americans. It is a language King spoke to goad them into action, one historian says.

King grounded his appeals for justice in the language of the Bible and the nation’s founding documents. In his “I Have a Dream” speech, King told his audience that his dream was “deeply rooted in the American dream.” In others he urged Americans to “be true to what you said on paper,” referring to the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

“That’s what made Martin Luther King Martin Luther King,” says Podair, history professor at Lawrence University in Wisconsin. “If you can do that in an eloquent way you can reach across to some white Americans and they will be moved. Then you’re speaking their language.”

BLM leaders, however, have made another tactical decision: They’re not going to try to adjust their message to reach white America.

“Black people for too long have been forced to refine our message according to what is comfortable for the mainstream,” says Brittany Packnett, one of the BLM movement leaders. “We have made a distinctive choice not to do it.”

That decision, to not couch their message to get white buy-in, can be seen in the BET speech by Jesse Williams, who said “the burden of the brutalized is not to comfort the bystander.”

“If you have no interest in equal rights for black people then do not make suggestions to those who do. Sit down,” Williams said.

Packnett says a movement can’t call for black freedom if its leaders don’t embody it:

“Our goal is to be free and authentic, not to pacify others.”

Even if BLM adapted its language, it would still be difficult to reach beyond its core supporters, says McCarthy, the Harvard historian. When King spoke of his dream, most Americans got their news from three television networks and newspapers. Today, more people live in media cocoons where they listen only to political voices they agree with, he says.

“You’re not going to get that 18 to 20 minute powerful speech on the Mall where you have MLK talking his dream,” he says. “We have so many more voices communicating in these spaces. Everybody tweets, Snapchats and posts on Facebook. Everybody has a platform.”

Reason No. 3: They’re not trying to mobilize the black church

Black protest movements have traditionally sought support from the black church. It is the most potent organizing force for political change in the black community. The most famous slave rebellion was led by a black preacher, Nat Turner. The black church powered the civil rights movement led by King. Today, contemporary black churches do everything from voting registration drives to educating people about Obamacare.

The BLM, though, is betting that a black protest movement can succeed without the explicit support of the black church. While BLM leaders work with individual black churches and pastors, they say on their website that “this current movement has a very different relationship to the church than movements past.”

“Protesters patently reject any conservative theology about keeping the peace, praying copiously, or turning the other cheek,” an unnamed essayist says on the BLM website. “Such calls are viewed as a return to passive respectability politics.”

The BLM is wary of the black church for several reasons. One is the makeup of its leadership. Some of BLM’s best-known leaders are women or gay, groups that have traditionally been marginalized by the black church.

And then there is the autocratic leadership style of many black pastors. Elzie says BLM has reached out to well-known black pastors who won’t join because they want to be in charge.

“If you want to be involved and be in the streets in the protests, that means knowing that you’re in the middle of the crowds and you’re not the leader,” she says. “It’s hard for some to be at the table if they’re not the one leading the conversations.”

“Traditional” civil rights leaders have also given BLM a mixed reception. The Rev. Andy Young, a close aide to King, recently called BLM protesters “unlovable little brats” but later apologized. The Rev. Al Sharpton criticized BLM protesters in Ferguson, Missouri, for not voting to change their city government. But the NAACP has adopted some of BLM’s rhetoric and even helped local BLM leaders organize. And Marc Morial, president of the National Urban League, said that BLM was “adding support and momentum” to the contemporary civil rights struggle.

A black protest movement, though, doesn’t need the widespread support of the black church to be successful, one historian says. King proved that.

Large segments of the traditional black church rejected King, says Clarence Lang, author of “Black America in the Shadow of the Sixties: Notes on the Civil Rights Movement, Neoliberalism, and Politics.” King was part of a “militant minority” in the black church because many of its leaders thought he was too radical, Lang says.

At a BLM rally it doesn’t matter if you’re straight, gay, well-dressed, white, transgender, young – all are welcome.

“One of the most promising aspects of Black Lives Matter is that it has been able to create a political space that allows African-Americans to participate openly from so many different identities and walks of life, including those outside the boundaries of what might be considered ‘respectable,’ ” says Lang, a professor of African and African-American studies at the University of Kansas.

Reason No. 4: Movements that don’t bend are broken

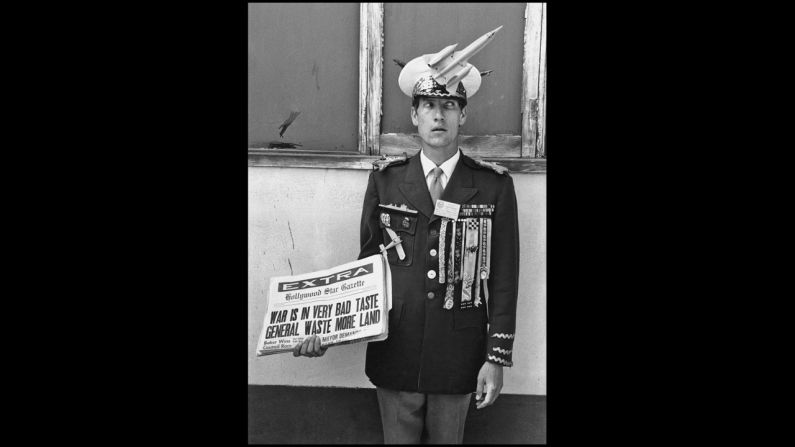

“No battle plan survives contact with the enemy.”

That’s a military adage that underscores the unpredictability of warfare. Great battles are often won not by genius strategizing but by chance events: a freak storm destroys a fleet of warships; an absentminded soldier loses crucial battle plans; a general falls ill on the eve of a campaign.

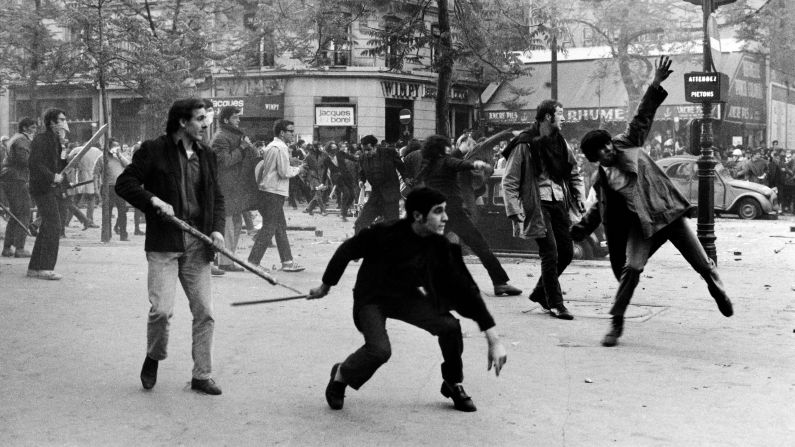

Protest movements often face the same abrupt reversals of fate, says Podair, the historian. He cites an infamous defeat from the union movement, the Homestead steelworkers strike.

The steelworkers union initially looked like it had won a bloody battle against a ruthless figure of the Robber Baron era, steel titan Andrew Carnegie. On July 6, 1892, thousands of unionized steelworkers successfully beat back 300 armed detectives who had been dispatched to the Homestead steel mill by Carnegie to crush the strike. They were protesting working 12-hour days, and six to seven day work weeks, and their plight earned sympathetic newspaper coverage across the nation.

That sympathy evaporated about three weeks later because of the actions of one gunman. An anarchist tried to assassinate Henry Clay Frick, Carnegie’s plant manager at Homestead and his designated union buster. Frick’s reaction – he and others subdued his would-be assassin after being shot twice and stabbed four times – made him a hero to the American public. The public then connected a mounting anxiety over anarchists to the striking steelworkers.

“The union disavowed the anarchist but it was too late,” says Podair. “The strike fails and the steelworkers don’t get a union going for another 30 years.”

History turns on a hinge; movements that don’t learn to adjust often fizzle, Podair says. He cites the example of Occupy Wall Street. It attracted support but didn’t have a Plan B after occupying Zuccotti Park near Wall Street.

“They did not adapt,” Podair says. “They were so protest- and spectacle-oriented that they never made the transition into electoral politics, which is where the power is in a democracy.”

McCarthy, the Harvard historian, doesn’t think Occupy Wall Street should be called a failure. Nor should it be judged by its power to get candidates elected.

“We wouldn’t have had a Bernie Sanders campaign if it wasn’t for the Occupy movement,” he says. “We wouldn’t have the language of the 1% or Democratic presidential candidates calling for more regulations of the banks.”

McCarthy says a better illustration of a movement’s need to adapt is the gay rights movement. It was devastated by the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. That’s when the gay community realized that it had to develop more confrontational and theatrical forms of protest because the nation’s political and medical community were ignoring the crisis, he says. ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), a new coalition of direct action groups, used high-profile demonstrations and acts of civil disobedience to further their agenda.

“The movement could have been derailed and died but they rose up, spoke up and acted up,” McCarthy says. “And that movement is still with us today.”

Will BLM still exist in the years ahead?

At least publicly, BLM leaders don’t speak of changing their approach.

Packnett says BLM has repeatedly said that it’s not violent or anti-police.

“We’ve all said that,” she says after a big sigh. “People hear what they want to hear. It doesn’t fit with the narrative that critics want to have.”

The future may produce more unexpected narratives for the movement. What if another black shooter attacks police and invokes BLM? What if new cell phone footage shows police officers, not unarmed black people, being gunned down? What if the names of Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland and slogans like “I Can’t Breathe” fade from public memory?

Will a “leaderful” movement that refuses to speak white America’s language adapt? Or will it squander the momentum built the last four years?

If the latter is the case, BLM leaders may confront this question in the future:

“Hey, whatever happened to Black Lives Matter?”