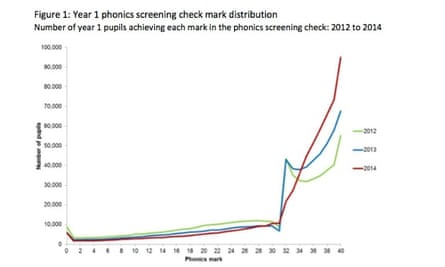

The phonics check, a simple test of reading given to five and six year-olds at the end of year one of primary school in England, comprises words and “pseudo-words” that children are expected to pronounce. In 2012 and 2013, the Department for Education announced in advance what the “pass” mark was to be. Looking at the chart below, with the yellow line for 2012 and blue line for 2013 results, can you guess what the pass mark out of 40 was?

If you guessed the pass-fail mark was 32: congratulations. That was the correct answer.

Now, what do you think the pass mark was in 2014, using the red line? Any ideas? Well, it was also 32. So what changed?

After 2012 and 2013 someone at the DfE noticed the unusual pattern. Rather than exhibiting any sort of empirical power-law distribution, as you’d expect in a situation such as this, in both years there was a steep shelf around 32 marks. The DfE then decided to not announce the expected mark in 2014, and bingo, a more normal distribution appeared in the results.

So what happened? Here’s the DfE’s bland narrative:

Teachers administer the screening check one-on-one with each pupil and record whether their response to each of the 40 words is correct. This mark is from 0 to 40 and for 2014, as in previous years, the threshold to determine whether a pupil had reached the expected standard was 32. In 2014, unlike previous years, this mark was not communicated to schools until after the screening check was completed.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the phonics check scores in each year from 2012 to 2014. In both 2012 and 2013, there was a spike in the distribution at a score of 32, the expected standard for those pupils who took part. However, this spike is not seen in 2014.

So in 2012 and 2013, did some teachers get to 32 and then stop, to spare their tiny pupils from further stress? Did the words tested get much more difficult from number 33 onward? Or did some teachers decide to fiddle the test?

Is there any way of finding out? Probably not. But the Chicago economist Steven Levitt and a colleague once wrote a paper – Rotten Apples: An Investigation of the Prevalence and Predictors of Teacher Cheating – and designed an algorithm to identify situations where teachers were likely to cheat in tests. They looked for suspicious patterns of answers, such as test papers where candidates failed easy questions but suddenly got harder questions right – because teachers found it quicker to fill in the tough questions at the end that their students didn’t touch, rather than erase and correct the earlier answers.

Their conclusion? “Our results highlight the fact that incentive systems, especially those with bright line rules, often induce behavioral distortions such as cheating.”

Update: datablogger @Jack_Marwood alerts me to a 2012 post by Dorothy Bishop, professor of developmental neuropsychology at Oxford University, who spotted the distribution issues in the very first phonics check results:

This is so striking, and so abnormal, that I fear it provides clear-cut evidence that the data have been manipulated, so that children whose scores would put them just one or two points below the magic cutoff of 32 have been given the benefit of the doubt, and had their scores nudged up above cutoff.

This is most unlikely to indicate a problem inherent in the test itself. It looks like human bias that arises when people know there is a cutoff and, for whatever reason, are reluctant to have children score below that cutoff.

Prof Bishop is on Twitter as @deevybee

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion