Days before she delivers her unequivocal Time’s Up speech at the Grammys – “We come in peace, but we mean business” – Janelle Monáe walks into an upper-level hotel suite in Manhattan, just as sunset begins to fade over the Hudson river. Her 5ft stature is amplified by a wide-brimmed hat and a warm, room-owning confidence. She is dressed in a fetching new arrangement of her preferred black-and-white palette: a slightly cropped top and flared pants, worn under a fuzzy black duster coat with massive white polka dots. Monáe’s uniform of suits and tuxedos, by her reckoning, is a fashion statement second, a political statement first – a homage to her working-class upbringing, she says.

Since her breakout more than a decade ago with the Fritz Lang–inspired EP Metropolis, and her critically acclaimed full-length debut The ArchAndroid, political statements have been at the core of Monáe’s work. She brought Afrofuturism and science fiction into R&B and pop; her public image was scripted according to the same otherworldly narrative. She has been nominated for six Grammy awards – although major chart success has eluded her – and successfully segued into acting, with key roles in Moonlight and Hidden Figures. It’s hard to believe, then, when she says, in her warm, down-to-earth Kansas-to-Atlanta accent, “I’m terrified.”

Monáe confesses it is the first time that she has talked about the two songs she is unveiling – initial glimpses of Dirty Computer, her first album since Electric Lady was released five years ago. “Has it been that long?” she says. “I don’t know. I live in the future! But I always knew I had to make this album. I had the title even before I made ArchAndroid.”

Last week she dropped a teaser for Dirty Computer and its accompanying narrative film (or rather, “emotion picture”). Fittingly, the 33-second trailer is being shown ahead of screenings of Black Panther, a film whose Afrofuturist storyline is in keeping with the themes of Monáe’s work. The dystopic teaser co-stars the actor Tessa Thompson, whose character is abducted by a figure in military uniform, and who later embraces Monáe on a beach; it cuts then to Monáe lying on an examination table as a series of haunting and cryptic flashbacks play in rapid succession and she narrates: “They drained us of our dirt, and all the things that made us special.”

The first two singles from Dirty Computer, Django Jane and Make Me Feel, seem like significant clues to the twin directions of the album. Django Jane is Monáe’s rallying cry, a rebellious protest anthem for women in general (“We gave you life, we gave you birth, we gave you God, we gave you earth,” she sings; a recent favourite book is The Great Cosmic Mother by Monica Sjöo, the Swedish proponent of the Goddess movement, which champions female deities) and for African-American women in particular (“Black girl magic, y’all can’t stand it”). She puts down mansplaining with a forceful, deadpan lyric: “Hit the mute button, let the vagina have a monologue.” It’s one of Monáe’s most political songs to date, and also one of her most personal, a revelation for a singer whose critics have called her presence “cerebral”, her music “controlled”, her “constructed” look.

“Remember when they used to say I looked too mannish,” she sings, in a pointed taunt. This is Monáe 2018: “One of the things I’m trying to learn to do is let go.” She says that letting go has come about in part thanks to therapy, and in part to translating political anger, as she ever more explicitly addresses wrongs against black Americans. Django Jane is “a response to me feeling the sting of the threats being made to my rights as a woman, as a black woman, as a sexually liberated woman, even just as a daughter with parents who have been oppressed for many decades. Black women and those who have been the ‘other’, and the marginalised in society – that’s who I wanted to support, and that was more important than my discomfort about speaking out.”

But Dirty Computer promises moments of danceable joy, too, and those also feel distinctly personal this time around. Make Me Feel, with a guitar groove that evokes Prince’s Kiss, is a song of desire and freedom, illustrated with an alluring “visual”, as Monáe prefers to call the video. It’s a colour-saturated club fantasy with 80s vibes, co-written by Monáe and directed by Alan Ferguson – AKA Mr Solange Knowles, who also directed Monáe’s videos for Electric Lady, Prime Time and, with Erykah Badu, Q.U.E.E.N. “We spent a lot of time making something very detailed that didn’t need a lot of explaining, that was just about the emotion,” she says.

The film features two characters played by the singer herself – the suit-wearing powerhouse Janelle Monáe and the free-spirited, slightly risqué Janelle Monáe who sashays into a club with Tessa Thompson; she sensuously accepts a lollipop from Thompson while locking eyes with a handsome guy. It may not need explaining, says Monáe, but gossip rags have wondered loudly whether these 33 seconds (and a seemingly affectionate red-carpet appearance) could mean that Monáe and Thompson are dating, or that Monáe is “finally” out of the closet.

Rumours have long been whispered about her sexuality, but Monáe has thus far resisted publicly defining it; she characterises herself again as “sexually liberated” and she declines to frame Make Me Feel in literal terms. “It’s a celebratory song,” she says. “I hope that comes across. That people feel more free, no matter where they are in their lives, that they feel celebrated. Because I’m about women’s empowerment. I’m about agency. I’m about being in control of your narrative and your body. That was personal for me to even talk about: to let people know you don’t own or control me and you will not use my image to defame or denounce other women.”

It’s an ugly phenomenon she has glimpsed on social media. “I see how people try to pit women against each other,” she says. “There are people who have used my image to slut-shame other women: ‘Janelle, we really appreciate that you don’t show your body.’ That’s something I’m not cool with. I have worn a tuxedo, but I have never covered up for respectability politics or to shame other women.

“I’m guilty feeling like I can’t just be,” she says. “Like either it’s this or it’s that, it’s black or it’s white. But there’s so much grey. And I think I’m kind of discovering the grey and realising it’s OK not to have all the answers, or to supply them.”

In the years after Electric Lady, Monáe turned her talents to playing other people – in Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight, the first LGBTQ film and the first film with an all-black cast to win the best picture Oscar; in Hidden Figures, about female African American Nasa employees; and, recently, in Channel 4’s adaptation of Philip K Dick’s dystopian Electric Dreams. She spoke movingly at the Women’s March on Washington in 2017 (“Remember to choose freedom over fear!”) and later that year launched the organisation Fem the Future, a pre-Time’s Up grassroots movement aimed at empowering women and those identifying as women, especially in the arts and music.

And she hasn’t been musically silent either. Monáe’s 2015 single Hell You Talmbout recounts a chilling list of names of African American victims of police brutality. It’s a Black Lives Matter song, a protest song. “You know, I spend a lot of time in the future,” Monáe says, her sheer warmth and sincerity cancelling out any self-parody, as she nods to her cyborg persona. “But to help the future sometimes you got to go back to the past, and sometimes you got to stay in the present.”

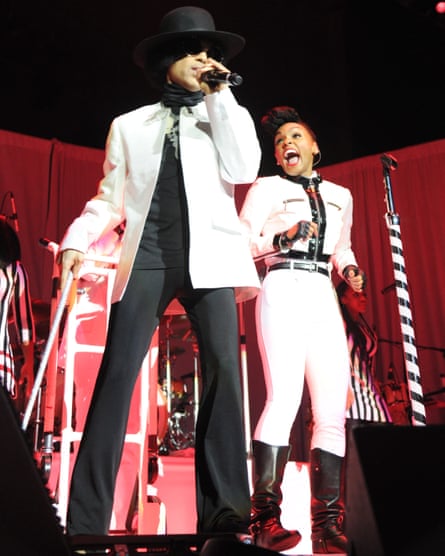

Monáe says the toughest part about staying living in the present in 2018 is moving forward in a world without her chief musical mentor. “It’s difficult for me to even speak about this because Prince was helping me with the album, before he passed on to another frequency,” she says. His sudden death was “a stab in the stomach. The last time I saw him was New Year’s Day. I performed a private party in St Bart’s with him, and after we sat and just talked for five hours. He was one of the people I would talk to about things, him and Stevie Wonder.” Both were among her earliest champions. Before The ArchAndroid was released, she sent each of them a copy, on CD-R, with a handwritten track list.

Prince not only encouraged her then, he lobbied for her first BET awards appearance and he performed on Electric Lady; when he died, he and Monáe were “collecting sounds” for Dirty Computer. “I wouldn’t be as comfortable with who I am if it had not been for Prince. I mean, my label Wondaland would not exist without Paisley Park coming before us,” Monáe says. She laughs a little. “He would probably get me for cussin’, but Prince is in that ‘free motherfucker’ category. That’s the category when we can recognise in each other that you’re also a free motherfucker. Whether we curse or not, we see other free motherfuckers. David Bowie! A free motherfucker. I feel their spirit, I feel their energy. They were able to evolve. You felt that freedom in them.”

Dusk is falling over the city as she gives this eulogy for her heroes, the artists who have so inspired her. “I dedicate a lot of my music to Prince, for everything he’s done for music and black people and women and men, for those who have something to say and also at the same time will not allow society to take the dirt off of them. It’s about that dirt, and not getting rid of that dirt,” she says, referring back to “the things that made us special” mentioned in the trailer.

Bowie and Prince probably did get scared too, Monáe reckons; her own risk is admitting her fears, which would seem to point to still more revelations to come in the full album. “Sticking up for those who are often left behind and don’t have a voice – doing that was one thing on film, but doing that in music is different because it’s all you,” she says. “So I can’t sit back here and tell you I’m confident and fearless. I’m terrified right now. Like, I don’t know how my family’s gonna react, I don’t know what people are going to say.”

What is the worst they could say? The thing she is most afraid of? She takes a deep breath. “I’m about to cry,” she says, and dabs briefly at her eyes as she collects herself. “I think – rejection. This may all be in my head, ’cause I have a tendency to overthink shit – I know that about myself. But I think: rejection. This started with me, with my feelings. But people want me to be an image that’s in their mind; what held me back was that I represent something to so many people and people put all this pressure on me to be just this one thing.”

She doesn’t specify what that one thing is. A pop star? A sci-fi goddess? A civil rights spokesperson? Perhaps she is shrewdly withholding further information for the album’s release. “Some of it is factual, some of it is fiction,” she says, “but it all started with me as the subject.”

What does seem to be clear is that the protection of her cyborg character seems to have been shed – Dirty Computer looks set to be her most human work yet. As she is ushered out by her team, she turns back, seemingly willing herself to be vulnerable. “This project was about painting in different colours, not just black and white; going in and allowing myself to use all the shades of the crayon box,” she says. “It was time to focus on being a complete, complex human being. I don’t know who’s gonna come with me and who’s gonna criticise me, but I’m not gonna renege, and I’m not gonna hide.” Somewhere, surely, her heroes are applauding.