In the digital age, what happened to newspapers will happen to universities. This was the startling proposition put to an audience of academics a few weeks ago within the 900-year-old walls of Durham Castle, by Peter Horrocks, vice-chancellor of the Open University.

What, asked Horrocks, is to stop platforms such as Facebook or LinkedIn – the latter has “unparalleled data about the qualifications and employment records of graduate professionals” – from teaming up with US universities to offer degree courses and modules on a global scale? What if multinational companies in the UK were to accept LinkedIn degrees and even prefer them to Russell Group degrees?

The age of “the fortress university”, in which “the academic was the custodian of knowledge” sheltering behind “high barriers to entry”, was nearing its end, Horrocks said. “I remember UK newsrooms scoffing at the idea that news consumption would move away from then dominant newspapers or broadcasters to digital aggregators. Who is scoffing now?”

Some may see Horrocks, 58, as a visionary, but to many OU academics his Durham speech confirmed their worst fears. On the university’s Milton Keynes campus, the language is apocalyptic. Although a protest letter to the Guardian signed by more than 100 staff was never sent (because, as one lecturer told me, “there’s an intense loyalty to the OU which, to some colleagues, is like a religion”), phrases such as “the end of the OU as we know it” and “betrayal of its history” circulate freely.

Since he became vice-chancellor in 2015, the OU has closed – despite opposition from the senate, its supreme academic body – seven English regional centres, which provided vital support to its students, of whom nearly 15% have special needs such as physical disabilities or mental health issues. They were replaced with what critics describe as call centres – and Horrocks as more accessible service centres – that open outside normal working hours.

Now Horrocks aims to save a quarter of the university’s £400m annual budget by closing courses and cutting jobs. Nobody denies economies are necessary. The dramatic nationwide fall in part-time students, especially since the introduction of higher tuition fees in 2012, has hit the OU hard, with student numbers down by a third between 2010 and 2016.

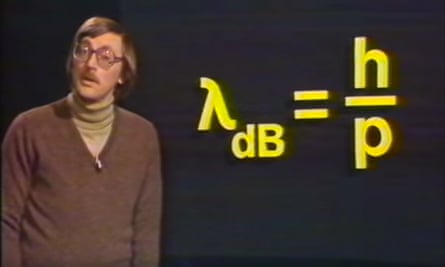

But much of the savings will go to changing “the university of the air” – where lectures were broadcast on radio and TV – into “the university of the cloud”. OU teaching is being re-designed so degrees can be taken, depending on students’ preferences, largely or wholly through digital learning.

Money will also go to FutureLearn, a commercial offshoot offering Moocs (massive open online courses) from the OU and other universities around the world. Seven million “learners” (in Horrocks’s word) already use its courses.

“Our worry,” one senior academic told me, “is that the current management is running the university down. They see its future not as an academic institution but as a media platform.”

Horrocks, his critics can reasonably say, has form. He came to the OU from the BBC, where he had spent his entire working life, latterly as head of the World Service. In an earlier job, he turned BBC news into a multimedia operation, to the consternation of its more traditional reporters who were upset when he said that aggregating and curating content, some of it from social media, was part of their job. “You’re not doing your job if you can’t do those things,” he said. “It’s not discretionary.”

When I meet Horrocks, who looks and dresses like a bank manager, he insists that, far from the OU becoming solely a media platform, it would strengthen its relationships with students. “A nurturing environment in which people can learn from each other absolutely has to be part of what the OU is, but in new ways,” he says.

The OU, established by the Labour government in 1969, always offered face-to-face tutorials, individually or in groups, in addition to distance learning, and these will still be available. “But people’s lives make it harder for them to attend face-to-face. I studied a maths module myself when I first arrived and quite often I found only one other student in a tutorial and sometimes I was alone. People need to be able to communicate digitally as a group.”

The national student survey casts doubt on this view. In 2010 and 2011, the OU topped the league tables for student satisfaction. Now it has fallen to 47th after the introduction of a complex new system for organising tutorials, many of them online, which was plagued by faulty IT. Horrocks talks of “teething problems”; his critics say the university went “to the brink of failure”.

“I’m not denying that the fall in satisfaction is a significant problem,” Horrocks says. “The main explanation is that, because of the rise in fees, students have become more demanding. Many used to study individual modules just for the pleasure of learning. Sadly, with fees three times higher than they were, we have fewer of them.”

We turn to FutureLearn which, he says, is based on the OU’s approach to pedagogy. “That’s why it’s not just a media platform. It’s social learning, learning from each other. Other universities may provide the content, the academic expertise and the actual teaching but we provide a platform with learning capabilities built into the software. It’s providing learning largely outside the UK, particularly in developing countries. So it’s highly effective for the British higher education brand,” Horrocks says.

The only other substantial English-language educational platforms are in the US, he says. “An alliance between one of them and a big technological player could have an extraordinary effect on British universities. Our cinema content is dominated by the US. It is not so far fetched to think the same thing could happen in education.”

UK newspapers, Horrocks said in his Durham lecture, never tried “to create a shared platform for value and quality in news content”. Universities were in danger of making the same mistake – until the OU’s “foresight” provided a “best of British universities” platform.

Many academics, however, see conflicts of interest between the OU and FutureLearn. It was recently announced, for example, that FutureLearn will provide the platform for 50 all-online degrees, initially postgraduate but possibly also undergraduate in future, offered by Coventry University. Why is the OU promoting its competitors’ courses, academics ask. “We could lose thousands of students,” said one.

Horrocks was born and raised in south London. His father was an optician, his mother a volunteer in Citizens Advice bureaux. He attended, with fees paid by the local council, the independent King’s College School in Wimbledon, where an early venture into journalism was seized and pulped because, he says, “it went too far in caricaturing teachers”. At Cambridge, where he got a first in history, he edited the university paper.

What drew him to journalism? “I’m quite a shy person and journalistic credentials allowed me to go places, ask questions and satisfy my curiosity.”

He joined the BBC from university as a reporter but switched to producing and editing. “I was told I might just make it as a reporter but I might be more successful if I wasn’t in front of a camera. I didn’t project myself well enough.” He had no regrets. “I realised the real control in TV lies with the editor and producer. They decide what goes in programmes.”

He edited Newsnight and Panorama before being promoted to management jobs. But in 2013 he was passed over for head of BBC News, perhaps because he had charge of programmes (on Jimmy Savile and, earlier, on the BBC’s handling of allegations about Tony Blair and the Iraq war) that, being critical of the corporation itself, did not “endear me to the hierarchy”, he says. Horrocks left the BBC without another job lined up, but was soon headhunted by the OU.

To his academic critics, he says: “The OU was set up as a wonderful social democratic institution. We’re now in a much more commercialised, marketised environment. Students have become consumers. The university has responded to that and needs to respond faster – in, for example, the focus on employability.”

Such language wins few friends among OU lecturers. “Many students still learn for pleasure,” one professor tells me. “But they are not getting an intellectual community as they once did. They get relationships based on emails. The Horrocks model for teaching is atomised and impoverished.

“A university degree isn’t just a few soundbites or some kind of social media adventure. I think universities should turn students into critical citizens. Horrocks wants to teach them how to use a smartphone.”

I ask Horrocks which group he has found more resistant to change: journalists or academics? “Academics,” he replies. “But it’s more important that they have independence of thought.

“Their job is to help students think critically. A vice-chancellor can hardly complain when they’re being difficult and argumentative.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion