Introduction

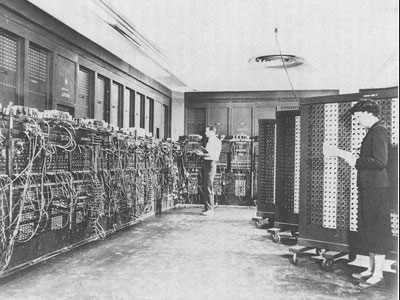

Electronic digital computers moved out of science fiction and into reality during World War II. Less powerful than a modern pocket calculator, the first real job for these massive machines was to speed up the calculation of artillery firing tables.

Thirty years later, computers had firmly cemented themselves in the public imagination. They were huge boxes, covered with blinking lights and whirring reels of tape. Banks and big corporations all had computer rooms, closely guarded by a priesthood of programmers and administrators. Science fiction novels and movies imagined impossibly brilliant supercomputers that guided spaceships and controlled societies, yet they were still room-sized behemoths. The idea of a personal computer, something small and light enough for someone to pick up and carry around, wasn't even on the radar.

Even the major computer companies at the time didn't see the point of small machines. The mainframe industry was dominated by IBM, who was the Snow White to the Seven Dwarves of Burroughs, CDC, GE, Honeywell, NCR, RCA and Univac. Mainframes took up entire floors and cost millions of dollars. There was also a market for slightly smaller and less expensive minicomputers, machines the size of a few refrigerators that sold for under a hundred thousand dollars. This industry was dominated by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), with strong competitors such as Data General, Hewlett-Packard and Honeywell-Bull. None of these companies considered the personal computer to be an idea worth pursuing.

ENIAC, the second electronic digital computer, circa 1943

It wasn't that the technology wasn't ready. Intel, at the time primarily a manufacturer of memory chips, had invented the first microprocessor (the 4-bit 4004) in 1971. This was followed up with the 8-bit 8008 in 1972 and the more-capable 8080 chip in 1974. However, Intel didn't see the potential of its own product, considering it to be useful mainly for calculators, traffic lights, and other embedded applications. Intel had built a reference design with a microprocessor and some memory that could be programmed using a terminal, but it was used for testing purposes only. An Intel engineer approached chairman Gordon Moore with the idea for turning it into a consumer product, but Moore, with a rare lack of insight, couldn't see any practical purpose for such a device and decided not to go ahead with the project.