A landmark trial for Huntington’s disease has announced positive results, suggesting that an experimental drug could become the first to slow the progression of the devastating genetic illness.

The results have been hailed as “enormously significant” because it is the first time any drug has been shown to suppress the effects of the Huntington’s mutation that causes irreversible damage to the brain. Current treatments only help with symptoms, rather than slowing the disease’s progression.

Q&AWhat is Huntington's disease?

Show

Huntington’s disease is a congenital degenerative condition caused by a single defective gene. Most patients are diagnosed in middle age, with symptoms including mood swings, irritability and depression. As the disease progresses, more serious symptoms can include involuntary jerky movements, cognitive difficulties and issues with speech and swallowing.

Currently there is no cure for Huntington's, although drugs exist which help manage some of the symptoms. It is thought that about 12 people in 100,000 are affected by Huntington's, and if a parent carries the faulty gene there is a 50% chance they will pass it on to their offspring.

Prof Sarah Tabrizi, director of University College London’s Huntington’s Disease Centre who led the phase 1 trial, said the results were “beyond what I’d ever hoped ... The results of this trial are of ground-breaking importance for Huntington’s disease patients and families,” she said.

The results have also caused ripples of excitement across the scientific world because the drug, which is a synthetic strand of DNA, could potentially be adapted to target other incurable brain disorders such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. The Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche has paid a $45m licence fee to take the drug forward to clinical use.

Huntington’s is an incurable degenerative disease caused by a single gene defect that is passed down through families.

The first symptoms, which typically appear in middle age, include mood swings, anger and depression. Later patients develop uncontrolled jerky movements, dementia and ultimately paralysis. Some people die within a decade of diagnosis.

“Most of our patients know what’s in their future,” said Ed Wild, a UCL scientist and consultant neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, who administered the drug in the trial.

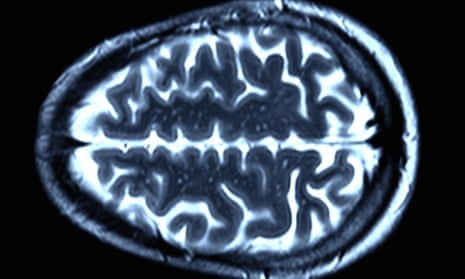

The mutant Huntington’s gene contains instructions for cells to make a toxic protein, called huntingtin. This code is copied by a messenger molecule and dispatched to the cell’s protein-making machinery. The drug, called Ionis-HTTRx, works by intercepting the messenger molecule and destroying it before the harmful protein can be made, effectively silencing the effects of the mutant gene.

To deliver the drug to the brain, it has to be injected into the fluid around the spine using a four-inch needle.

Prof John Hardy, a neuroscientist at UCL who was not involved in the trial, said: “If I’d have been asked five years ago if this could work, I would have absolutely said no. The fact that it does work is really remarkable.”

The trial involved 46 men and women with early stage Huntington’s disease in the UK, Germany and Canada. The patients were given four spinal injections one month apart and the drug dose was increased at each session; roughly a quarter of participants had a placebo injection.

After being given the drug, the concentration of harmful protein in the spinal cord fluid dropped significantly and in proportion with the strength of the dose. This kind of closely matched relationship normally indicates a drug is having a powerful effect.

“For the first time a drug has lowered the level of the toxic disease-causing protein in the nervous system, and the drug was safe and well-tolerated,” said Tabrizi. “This is probably the most significant moment in the history of Huntington’s since the gene [was isolated].”

The trial was too small, and not long enough, to show whether patients’ clinical symptoms improved, but Roche is now expected to launch a major trial aimed at testing this.

If the future trial is successful, Tabrizi believes the drug could ultimately be used in people with the Huntington’s gene before they become ill, possibly stopping symptoms ever occurring. “They may just need a pulse every three to four months,” she said. “One day we want to prevent the disease.”

The drug, developed by the California biotech firm Ionis Pharmaceuticals, is a synthetic single strand of DNA customised to latch onto the huntingtin messenger molecule.

The unexpected success raises the tantalising possibility that a similar approach might work for other degenerative brain disorders. “The drug’s like Lego,” said Wild. “You can target [any protein].”

For instance, a similar synthetic strand of DNA could be made to target the messenger that produces misshapen amyloid or tau proteins in Alzheimer’s.

“Huntington’s alone is exciting enough,” said Hardy, who first proposed that amyloid proteins play a central role in Alzheimer’s. “I don’t want to overstate this too much, but if it works for one, why can’t it work for a lot of them? I am very, very excited.”

Prof Giovanna Mallucci, associate director of UK Dementia Research Institute at the University of Cambridge, described the work as a “tremendous step forward” for individuals with Huntington’s disease and their families.

“Clearly, there will be much interest into whether it can be applied to the treatment of other neurodegenerative diseases, like Alzheimer’s,” she added. However, she said that in the case of most other disorders the genetic causes are complex and less well understood, making them potentially harder to target.

About 10,000 people in the UK have the condition and about 25,000 are at risk. Most people with Huntington’s inherited the gene from a parent, but about one in five patients have no known family history of the disease.

The full results of the trial are expected to be published in a scientific journal next year.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion