- India

- International

The failed coup: Unravelling of Turkey’s Islamist ascendancy

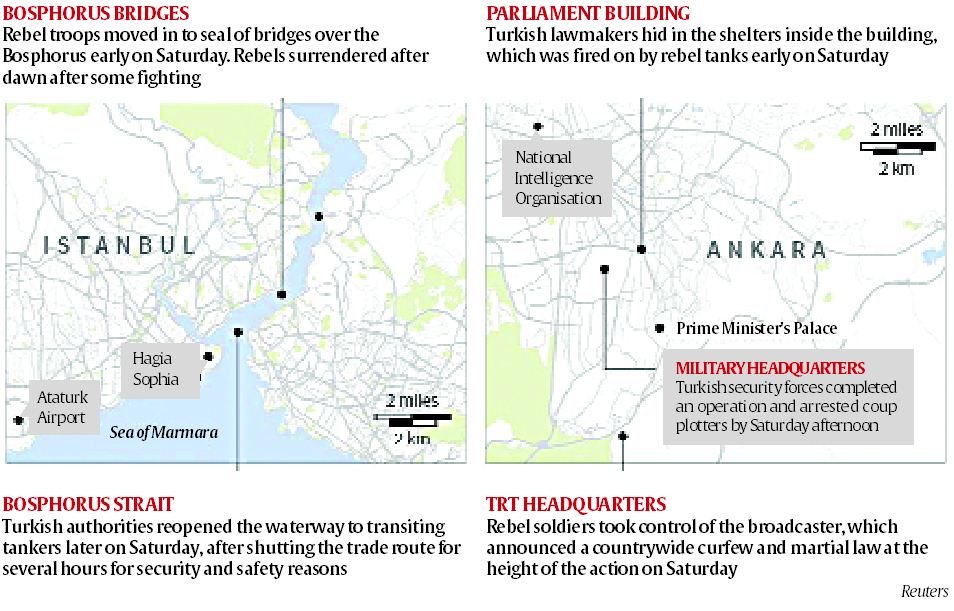

Violence shook Turkey’s two main cities for several hours overnight on July 15, as an armed faction which tried to seize power blocked a bridge in Istanbul and strafed the headquarters of Turkish intelligence and parliament in Ankara.

A supporter of Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan is silhouetted against a Turkish flag during a demonstration outside parliament building in Ankara on Saturday. After the weekend’s events, Turkey’s Islamist government now has a tough choice: to try and hold on to power with ever-greater repression, or to risk unravelling. (Spurce: Reuters)

A supporter of Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan is silhouetted against a Turkish flag during a demonstration outside parliament building in Ankara on Saturday. After the weekend’s events, Turkey’s Islamist government now has a tough choice: to try and hold on to power with ever-greater repression, or to risk unravelling. (Spurce: Reuters)

Hoçaefendi Fethullah Gülen, Lord-Master of the secretive mystic order which bears his name, gathered his inner circle around him in the summer of 1998, to lay out his plans to transform Turkey into an Islamic State. He wanted no guns nor bombs. “You must move in the arteries of the system without anyone noticing your existence” the cleric explained to his followers, “until you reach the very centres of power”. Timing was key, else “the world will crush our heads, like in the tragedies in Algeria, like in 1982 [in] Syria; like in the yearly disasters and tragedies in Egypt”.

READ | Over 260 killed, 2,800 soldiers held as citizens foil Turkey coup

Turkey’s government has now blamed Gülen for the weekend’s putsch attempt that claimed at least 265 lives.

General Adem Huduti, the commander of the 2nd Army, General Erdal Öztürk, the commander of the 3rd Army, eight Army generals and eight other Air Force generals, are alleged by the government to have acted on Gülen’s orders.

This one thing is also clear: the stoically-secularist leadership of Turkey’s armed forces opposed the putsch, along with the mainstream secular opposition.

Little hard evidence has emerged, so far, to link Gülen to the plotters — though Generals Huduti and Öztürk, Turkish government officials say, are known to be linked to the spiritual orders. The cleric, who has lived in the United States for almost two decades, has denied the allegation.

Turkey’s Islamist movement, though, faces a historic fracture — holding out the risk of great instability in a country already buffeted by the violent jihadist storms to its east.

Supporters of Tukish President Tayyip Erdogan celebrate after soldiers involved in the coup surrendered on the Bosphorus Bridge in Istanbul, Turkey July 16, 2016. Reuters/Yagiz Karahan

Supporters of Tukish President Tayyip Erdogan celebrate after soldiers involved in the coup surrendered on the Bosphorus Bridge in Istanbul, Turkey July 16, 2016. Reuters/Yagiz Karahan

The mystic and the politician

In recent weeks, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has angered many among his Islamist following with an extraordinary policy volte-face.

Erdogan has restored ties with Israel, apologised to Russia for shooting down a jet operating over Syria, and even repaired his country’s relationship with Egypt — a country bitterly hostile to the Muslim Brotherhood, a party with close ties to Turkey’s ruling Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi.

Till 2012, or so, Lord-Master Gülen and President Erdogan were allies against the common cause of dismantling Turkish secularism. Gülen had no express political ambitions.

Born to a conservative middle-class family, Gülen joined the order of Sheikh Sa’id-i Kurdi, the founder of the Nur, or Light, movement. Kurdi had opposed the radical secularism of Turkey’s founding patriarch, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, in its first Parliament; defeated, he turned to setting up a spiritual movement that, with the help of the Central Intelligence Agency, wielded influence across Soviet Central Asia.

Gülen himself had a rough ride: in 1971, the Turkish security service arrested him for clandestine religious activities, such as running illegal summer camps to indoctrinate youths.

In 1981, he was forced to resign as a cleric, and fled the country in 1998, when his secret call for an Islamic state was leaked.

For Gülen, the alliance with Islamist politics guaranteed protection for his empire. He controls thousands of top-tier secondary schools, colleges, and student dormitories throughout Turkey — commanding the loyalty of a large cohort of the higher bureaucracy.

The alliance between the two worked well — till Erdogan realised Gülen was, in fact, running the state he ruled. From 2012, the pro-Gülen judiciary and police locked horns with Erdogan’s intelligence services, over the conduct of policy in Kurdistan.

Things finally came to a head in 2014, when Istanbul prosecutor Zekeriya Oz, a Gülenist, arrested the sons of three ministers, businessmen and bureaucrats, recovering millions of dollars in gold-for-oil trade with Iran, bypassing European Union and United States sanctions.

People chant slogans during a pro-government rally in central Istanbul’s Taksim square, Saturday, July 16, 2016. (AP Photo/Bram Janssen)

People chant slogans during a pro-government rally in central Istanbul’s Taksim square, Saturday, July 16, 2016. (AP Photo/Bram Janssen)

Islam at the ballot box

For a full understanding of the battle, though, one has to go back to the battles inaugurated by the Turkish state’s birth in 1923. No Muslim-majority society, arguably, has experienced reforms as radical: madrasas were banned, along with religious orders; the Persian script replaced by the Latin alphabet; the display of religious symbols in public spaces prohibited; Western-style dress promoted by law; Islamic law replaced by European civil codes; women granted suffrage.

From 1946, though, when a democratic multi-party system came into place, religion became a tool to compete for votes — with fateful consequences for the republic’s civic fabric. Thus, in 1948, voluntary religious education was added to the primary school curriculum, and seminaries to train clerics were opened — one, a college of theology at University of Ankara.

In the election of 1950, seven of 24 parties fought on a platform of giving religion a greater role in society — a promise that appealed to conservative peasants, small businessmen, and members of religious brotherhoods.

Adnan Menderes’ right-wing Demokrat Partisi came to power, and ushered in a tide of state-backed religious rebuilding.

Nur and other orders provided an important backbone for these activities. The alliance between the religious orders and the Islamists worked for both, but left a question unresolved: who was actually in charge, the clerics or the politicians?

People gather at a pro-government rally in central Istanbul’s Taksim square, Saturday, July 16, 2016. Forces loyal to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan quashed a coup attempt in a night of explosions, air battles and gunfire that left some hundreds of people dead and scores of others wounded Saturday. (AP Photo/Emrah Gurel)

People gather at a pro-government rally in central Istanbul’s Taksim square, Saturday, July 16, 2016. Forces loyal to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan quashed a coup attempt in a night of explosions, air battles and gunfire that left some hundreds of people dead and scores of others wounded Saturday. (AP Photo/Emrah Gurel)

The Turkish army struck back in 1960, imprisoning Menderes and outlawing the Demokrat Partisi. Its pursuit of economic modernisation through that decade, though, inflicted massive economic hardship which gave the Islamists renewed opportunity.

In the late 1960s, Mehmed Zahid Kotku, a Sheikh, or leader, of the Naqashbani Sufi order — from which the Gülen cult branched off — began holding widely-attended discourses at which he expounded on texts by Egyptian and Pakistani Islamists, notably Maulana Abul ’Ala Maududi. Helped by the spectacular defeat of secular Pan-Arab forces by Israel in 1967, Kotku cast Westernisation as key to Turkey’s problems, and evoked the glories of its imperial past.

Turkey saw its second military coup in 1971 — this sparked off by violent clashes between this new right, and a violent new left. In coming years, the army itself became increasingly dependent on Islam for legitimacy — in part the result of a US arms embargo that followed the occupation of Turkish Cyprus.

Following the the 1980 coup, the military nationalised Islam, as it were, ordering the expansion of state-run religious services, the introduction of religious education as a compulsory subject in public schools, and the use of the Diyanet, the state agency for religious affairs, for the “promotion of national solidarity and integration”.

Coup attempt by a group within the Turkish army against the President created law and order problem on Friday night. (Source: AP)

Coup attempt by a group within the Turkish army against the President created law and order problem on Friday night. (Source: AP)

The Erdogan years

From 2003-2009, during Erdogan’s early phase as Prime Minister, he presided over what some scholars have called Market Islamism — pushing cultural causes, like the headscarf or religious education, but within a framework of economic liberalisation. Long-standing problems with Iraq and Syria over the Kurdish issue were resolved. Erdogan pushed back against the military on many of these issues.

The commentator Nuray Mert has noted that Erdogan’s battles against the military’s power in Turkey were driven not by principle, but “by the desire of eliminating a secularist power centre”.

Islamist leaders appeared to be willing to be patient. “It is a painful spring that we live in”, Gülen said in one sermon. “It won’t be easy for a nation that has accepted atheism, has accepted materialism, a nation accustomed to running away from itself, to come back riding on its horse.”

But then in 2009 came the Arab Spring — and the moment of destiny Islamists like Gülen had long fantasised of. The new foreign minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, declared that Turkey sought a born-again Ottoman Empire, in which Istanbul would “reintegrate the Balkan region, Middle East and Caucasus” through Islamist parties.

The plan backfired badly. Egypt’s military, panicked by the Islamist excesses of its elected government, cracked down hard. Saudi Arabia, fearful of the growing power of the Muslim Brotherhood, threw its weight against the jihadists.

READ | Turkey military coup: Full coverage

And most important, as the Turkish-backed rebellion in Syria degenerated into chaos, the Islamic State and al-Nusra swatted Turkish-backed Islamists to take centre stage. Iran backed Syria, and, taking advantage of the chaos, Turkey’s historic adversaries, the Kurds, emerged empowered.

Faced with the complete failure of these policies, a slowing economy, Islamist terrorism at home and a growing Kurdish insurgency, Erdogan is now trying to turn the clock back — but, as the attempted putsch illustrates, it is a perilous business.

Erdogan’s anti-Gülen purge, in 2014, may be remembered as the first of a series of missteps which created a reservoir of resentment that eventually proved his undoing. Those with reasons to feel betrayed by his policies now include the thousands of Islamic State and al-Nusra fighters he encouraged to pursue jihad in Syria, the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood that was given a base in Istanbul only to be left out in the cold, and a Kurdish leadership that he once sought peace with, but then turned on.

Turkey’s Islamist government now has a tough choice: to try and hold on to power with ever-greater repression, or to risk unravelling. Either way leads to great peril — and, possibly, to perdition.

May 06: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05