-

A sperm whale swimming just below the surface.

-

Sperm whales live in small family units, and these families form groups called clans.

-

A sperm whale family shares its unique language dialect with other members of its clan.

-

Sperm whales dive incredibly deep to hunt, and in the Pacific they swim so far away from each other that they may never see the same whales twice in their lifetimes.

-

In the Caribbean, there are two sperm whale clans, each speaking a different dialect.

-

When sperm whales meet each other, they often exchange a unique coda, or word, which identifies their clan.

-

Sperm whales in the Caribbean have a dramatically different culture from whales in the Pacific.

-

Researchers studying sperm whales identify individuals from their unique tail shapes.

-

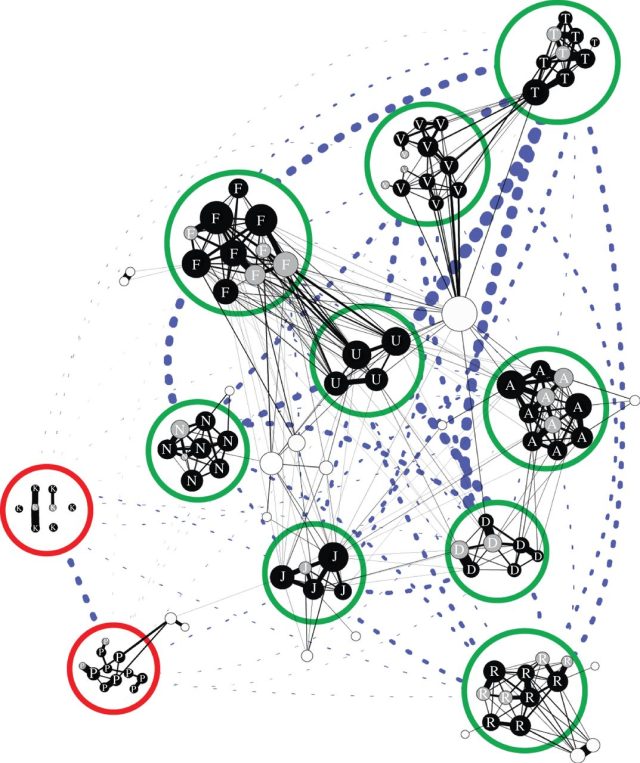

Here are some of the sperm whales of the Caribbean.

-

Researchers can also identify sperm whales by the markings on their bodies.

-

Sperm whales in the Caribbean, like the ones in this family unit, tend to be more "individualistic" than the ones in the Pacific.

-

Every sperm whale identifies him or herself using a call known as "five regular." It's five rapid clicks, with a slight variation for each individual.

-

When sperm whale families meet up, they often exchange codas in such rapid succession that it sounds like a human family reunion.

-

This sperm whale is basically goofing around.

-

Using drones, researchers can follow sperm whales more easily, watching from above.

-

Shane Gero and his team recently discovered a new clan of two families in the Caribbean, who have their own dialect and traditions.

-

This research vessel came all the way from Nova Scotia to do observations of Caribbean sperm whales.

-

Recording the whale's dialects.

Sperm whales share something fundamental with humans. Both of our species form groups with unique languages and traditions known as "cultures." A new study of sperm whale groups in the Caribbean suggests that these animals are shaped profoundly by their culture, which governs everything from hunting patterns to babysitting techniques. Whale researcher Shane Gero, who has spent thousands of hours with sperm whales, says that whale culture leads to behaviors that are "uncoupled from natural selection."

Gero and his colleagues recently published a paper on Caribbean whale culture in Royal Society Open Science, in which they describe the discovery of a new clan. Though this clan may have lived in the Caribbean for centuries, it's just coming to light now because sperm whales live and hunt in vast territories. This makes them hard to track. Like many scientists who study these wide-ranging creatures, Gero observes them by lowering specialized microphones into the water and recording the sounds they make to communicate.

Scientists working throughout the world have identified 80 unique "codas," the sperm whale equivalent of words, which they produce by emitting sounds called clicks. Each sperm whale clan has its own dialect, a unique repertoire of codas shared only with the other families who make up their clan. In the Pacific, there are five known dialect clans, and many of them co-exist in the same general regions without ever interacting. Atlantic whales have their own dialects too, and in the Caribbean there are two known clans.

Sperm whale society is very complicated, and every whale belongs to multiple social groups. Individuals spend most of their time in small family units, and multiple families converge to form larger groups. All the groups who share a dialect form a clan, and members of a clan may be so widely dispersed that they never meet one another even though they speak the same language. Families are made up of adult females and calves, while adult males tend to roam widely between clans and sometimes even swim from one ocean basin to the other. But even these general social structures vary a lot between oceans.

Gero says that Caribbean sperm whales spend most of their time in families of 5-7 animals rather than multi-family groups. Within these families, it's possible to observe friendships forming between individuals who spend more time together than with other family members. Caribbean whales also form friendships at the family level; often the same two families will swim together over the years while others basically ignore each other. In the Pacific, by contrast, scientists have never observed friendships between individuals. No two adult whales are ever spotted together more than once. That said, clans in the Pacific are much more tightly knit. Pacific sperm whales who speak the same dialect will form groups without any apparent preferences for certain families or individuals. Though these are clan differences, there are cultural differences at the family level too. In some families, calves are nursed by multiple females, while in others the calf nurses only from its biological mother.

It's likely that clan differences originated as responses to environmental challenges. In the Pacific, sperm whales roam over vast distances, and the animals' natural range stretches from pole to pole. By comparison, whales in the Caribbean are rarely more than 400 kilometers apart, which isn't much when you consider that they can swim up to 50 km per day. Pacific whales, whose ranges are on the order of thousands of kilometers, are less likely than their Caribbean counterparts to meet the same whale again. As a result, they may not be as choosy about which clan members they befriend. Whales in the Pacific are also more vulnerable to predators like orcas, so it's probably more advantageous for these whales to help all members of the clan equally, as a defense against attacks. Gero describes Caribbean whales as more "individualistic," while their Pacific cohorts have "an us-versus-them attitude" about their clans.

Sperm whale speech

A lot of the information we have about whale culture comes from analyzing their dialects. By recording individual whales in conversation, Gero and other researchers have tracked families, groups, and clans over time. In the Caribbean, for example, there's one distinct coda that Gero and his colleagues have heard repeatedly over the past 30 years. Called the 1-1-3 coda, it's a series of two clicks followed by three clicks in a rather catchy rhythm. Each family teaches new calves the coda, precisely duplicating the pattern used by every family in the clan. "This is an indication that that call is really important for all the families," Gero told Ars. "It's a marker of their cultural heritage. They're basically saying, 'I'm from the eastern Caribbean.'"

There are 20 unique codas among Caribbean sperm whales, but there is one coda that they share with sperm whales throughout the world. It's known colloquially among human scientists as "five regular." Every sperm whale broadcasts this series of five rapid clicks, but with slight variations that serve as the whale's "name" or signature call. A whale might use the five regular as a greeting, or as a signal to a distant companion that she's still in the area.

Gero said sperm whales use language to find companions and allies, just the way humans do. "Among early humans, language was used as shorthand for suite of values and behaviors and norms," he explained. "Groups of people walked around and met strangers and used language to decide whether to cooperate. A shared language meant shared norms, including where you lived and how you gathered food. Having these dialects means that sperm whale society is socially segregated. It means that cultural identity is important to these animals." And language is the vehicle they use to express culture.

Of course, human culture is dramatically different from whale culture. Humans are obsessed with making tools, from pottery bowls to computers, and whales don't appear to have any material culture or art. But as Gero puts it, "There’s no doubt that these animals are sharing and learning in an inheritance system [of language] that’s completely distinct form genetics. It's uncoupled from natural selection."

Cultural evolution and extinction

Richard Dawkins' 1970s book The Selfish Gene popularized the idea that small units of meaning called memes evolve like genes. But long before that, evolutionary biologists had observed units of culture, like sperm whale codas, spreading through populations. Sometimes the presence of a particular cultural idea means one clan survives when another one doesn't. But just as often, a piece of culture is more like the 1-1-3 coda. Its rhythm can't prevent whales from being eaten by predators, or show them where the tastiest octopuses live. Instead it just serves as a form of identity with other whales, a signal that says they can share resources and knowledge.

Sperm whale clans are diverse, but even at the family level we can see behaviors that are completely unique. When adolescent males leave home, they strike out for the seas beyond the clan. For a long time, scientists thought this journey began when the young males got a burst of testosterone that sent them wandering. But recently, through close observation, they discovered that it's the adult females in a family who initiate these walkabouts. When a male reaches his late teens, and his mother gives birth to another calf, the family stops including him in their social rituals. Males respond very differently to this treatment. Some meet up with other young males and form small groups, roaming the seas together. The males communicate using "clacks" instead of "clicks," abandoning the dialects of their clans until they return home many years later.

But Gero and his colleagues observed one male who refused to leave home. He followed his family for two years after they pushed him out, finally leaving only once he'd met another young male whom he could team up with. No one is entirely sure why one male leaves quickly while another stays with his family, nor do they know what happens to the roving males who move between clans as they search for mates. What we do know is that when adult males approach a new clan, they speak in codas "that we've never heard before," Gero said. We've only just begun to untangle the complexity of these animals' cultures.

Knowing that sperm whales have cultural identities means that we can no longer think of different whale groups as interchangeable. A sperm whale from the Caribbean acts and communicates very differently from a Pacific sperm whale, and conservationists worry about preserving this kind of diversity. "What does it mean to lose a sperm whale culture?" Gero asked. It wasn't a rhetorical question. The whales in the Caribbean have a calf mortality rate of 29% during the first year of life. The families who identify themselves with the 1-1-3 clan are suffering from a steady population decline, Gero said, as they die from "ship strikes, getting tangled in fishing gear, and chemical contaminants from agriculture." If the 1-1-3 clan goes extinct, we can't fix that by plunking a new group of sperm whales into the Caribbean—the newcomers wouldn't have the cultural background to survive in that specific environment. "It would be like asking a New Yorker to survive in the Amazon," Gero said. "Maybe they would last a few days, but they wouldn't do as well as the local people."

There are roughly 200,000 sperm whales in the world today, but each one comes from a unique culture, with its own dialect and traditions. "It’s easy to forget that they are always out there hunting, and babysitting, and playing, and avoiding predators; while we watch a match for the EURO2016, check Twitter, and order pizza," Gero mused. "Their lives go on mostly unnoticed by ours, but they have been out there roaming the oceans for generations before we came along, and the weight of that shared history should greatly affect our motivation for ocean conservation." By "shared history" Gero doesn't just mean how long we've spent on the planet with these enormous, deep-water hunters. He means humans and whales' shared experience of history itself, of cultural identity, and knowing where you fit into a social world that's defined by something greater and more ineffable than genetics.

Listing image by Photo Courtesy of The Dominica Sperm Whale Project

reader comments

87