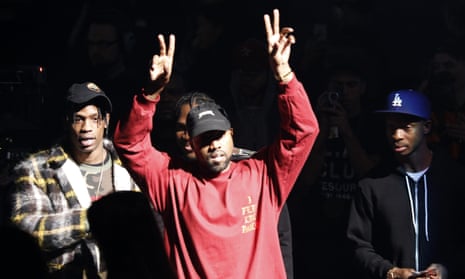

On 8 January, Kanye West announced via Twitter that his seventh studio album, then named Swish but now titled The Life Of Pablo, would be released on 11 February. That day, which was later punctuated by an album premiere event at Madison Square Garden, came and went, but the album was not available to stream or purchase anywhere, save for low-quality audio rips from the event that made their way online.

The album was eventually released a few days later on 14 February, so by traditional standards, that should have meant but the album was done, finished, whole. Except Kanye still doesn’t believe that the album is complete yet – despite its current widespread availability – and is supposedly still working on it.

This unprecedented situation forces reconsideration of what an album is today, or what it might become over the next few years. We’ve previously explored the modern album release cycle and the changing role of the album, but what if the definition of an album is also changing?

The 12in, long-playing vinyl album was first introduced by Columbia records in 1948, its 20-minutes per side corresponding roughly to the movements of a symphony. In the ‘60s, with bands such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones exploring the boundaries of pop, the studio album evolved from an assemblage of singles and lesser tracks to a more unified work which moved through two halves – the first side and the second side.

A generation later, while the CD took away the need to interrupt the flow of music, and also allowed musicians to make much longer records (the limit was 74 minutes, set by Sony president Norio Ohga when the format launched in 1980, as that was the length of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony), the album did not fundamentally change.

Even when the internet became the primary way fans consume music in the 2000s, and it was easier than ever to buy one track at a time and construct playlists, rather than slog your way through filler, artists still largely released albums in the traditional way, as if they remained fixed physical objects rather than computer files in flux. Once an album was out, there was no changing it – aside from remasters or deluxe editions a few years down the road, like the Beatles’ re-release of Let it Be, which stripped out Phil Spectors’ orchestration.

Nevertheless, such releases are generally regarded as curios for fans, rather than part of the artist’s canon. Records that revisit old songs, like the famously perfectionist Kate Bush’s peculiar 2011 album Director’s Cut, which sought to “correct” tracks from her two albums The Sensual World and The Red Shoes, are few and far between and usually regarded quizzically by fans – few said that they preferred the new versions to the originals.

But the internet is mutable, and digital products can be altered after they’re released. Video games already do this, offering patches and updates for years after the game’s original release date with the intention of improving the gameplay experience. Should albums be subject to the same treatment? Could this be the internet’s contribution to the evolution of the album as a format?

That depends on if the album is seen as a time capsule chronicling a creative period with a definite beginning and end, or as something that can continue to evolve, which is only completed when the artist has had enough of upgrading it. Artists have often seized the chance to upgrade and update their old material in concert, but now they can – in theory – do it on record too. But is this something that we, the listeners, really want?

Arthur William Radford once said that “half of art is knowing when to stop”. This idea ties into the “creator’s curse”, which was nicely defined by webcomic Cyanide and Happiness: “When you’re done making something, you improved while working on it. So you’re never fully satisfied with your own work, so you make more! Then it goes on like this forever and ever! Isn’t that neat?”

The urge to perfect something can mean that interesting flaws get airbrushed out. For instance, while U2 was working on their 1997 album Pop, their manager had booked the band’s upcoming tour before the album was completed. Various circumstances led to the band not having as much time as they wanted to work on the record, and the band was ultimately unsatisfied with the product upon its premature release.

Like The Life Of Pablo, U2’s Pop went through multiple titles alarmingly close to its release, and the band also tried to “fix” their album with markedly different track edits that were either released as singles or featured on the compilation album The Best of 1990–2000. Today, however, Pop is a fan-favorite U2 album, and it was even well-received at the time as a bold and experimental record, although it was a comparative sales disappointment. As for the updated songs, those are seen as auxiliary, not truly a part of the album, and not a right to the album’s wrongs.

So as it stands right now The Life Of Pablo might have what West sees as flaws, but isn’t the relatively rough nature of the album perfectly representative of the madness that led up to its release? Doesn’t it perfectly define this period of his life? Kanye may have put it best himself in a recent tweet: “I’m an artist… the definition of art - or at least my definition – is to be able to see the truth and then express it...”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion