Numbers are great, aren’t they? Just look at all the things you can do with them. You can add, subtract, divide. You can calculate the number of atoms in the known, observable universe, or the times you had to ask your daughter to tidy her room; use them to order more than one pizza, underestimate the pace of global warming or exaggerate the size of things as various as planets and fish that got away. For quantitative assessment, numbers rule.

The trouble starts when we confuse matters of quantitative value with qualitative value, a danger I found myself pondering afresh this week as debate raged over the perhaps terminal travails of Twitter. Of all the explanations offered for the platform’s apparent decline, the one never mentioned was maths, but I think that’s where the platform’s problems lie, being a concentrated reflection of our own. In a week when the withdrawal of a teenage social media maven (Essena O’Neill, 612,000 followers) from Instagram caused such a stir, it’s also worth asking whether this might mark the start of a broader social media unravelling.

First to Twitter, which, after years of steady growth, appears to have stalled. Back in January, Jason Calacanis, one of the beadiest commentators on these issues, predicted that the impending arrival of video on Twitter would entice 100 million new users. It didn’t, and neither did the powerful new capacity to live-stream images, using the platform’s Periscope adjunct. Twitter remains in essence an immensely useful application, turning individuals into mini-broadcasters, while allowing them also to create their own bespoke news service simply by choosing who to “follow” on the site. So why is the San Francisco-based company laying off almost 10% of its workforce, after posting a near-$600m loss last year as user growth flatlined?

Twitter has certainly made some bad decisions. Last week’s announcement that the useful “favourite” button would be replaced by a soppy heart-shaped “like” tab was one of them, leaving no way to acknowledge something without appearing to celebrate it (tsunami in Japan? Super!); the 2010 decision to shun third-party developers, thereby reinforcing the corporate bubble, was another. Some commentators point to the rise of notional rivals such as Instagram and Snapchat, but these impact on Twitter no more than the success of women’s football impacts on prawn farming in Malaysia – they’re different things.

Far more credible are complaints about Twitter’s slow response to the explosion of misogynistic trolling three summers ago. This was not just Twitter’s problem: a few years back, the aforementioned Calacanis sat down opposite me in a restaurant and asked bluntly, “Why are you such as asshole?” I blushed. He blushed. And this, he explained, was the point, because while saying what he’d said confused and unsettled me, it also cost him. “Now the hairs on the back of my neck are standing up,” he said, “because I’ve said something I feel I shouldn’t have.” Online, this human reflex is lost.

Caitlin Moran has pointed out that Twitter had been a place women liked and in which they’d felt free up to then, so the company’s mealy-mouthed response to trolls, no doubt influenced by Silicon Valley’s house libertarianism, was doubly disappointing. Certainly, some high-profile women left, but I don’t buy this as the whole story. The Daily Mail has been trolling the whole of Britain for decades and doing just fine on it, after all.

So to the numbers and why Twitter’s problems are not just Twitter’s problems. As our gatekeepers and arbiters of power have become more remote; and the possibility of meeting a bank manager who knows you, of talking to the person who decides what your child will learn, invests your pension, mediates your relationships, has receded, so a new way of assessing the value and efficacy of these things had to be found. What would you use for this but numbers? Which is why the people with the most influence on our 21st century lives (far more than the politicians we elect, as 2007-8 demonstrated) tend to be number crunchers – financiers, accountants, computer coders, marketeers.

And here’s where it gets interesting, because seen like this, Twitter starts to look less like an inept outlier than a microcosm, even test case. Why? Because Twitter’s problem is the same as everyone else’s, in that worth, value, status in its realm are measured in numbers, specifically numbers of followers. In order to get followers, users can a) be celebrities or b) be super-entertaining. Or, given the inconvenience of those paths to popularity, two more common routes are c) seeking out and following people who will automatically follow you back and unfailingly following all who follow you and d) buying software that accomplishes the same thing in seconds.

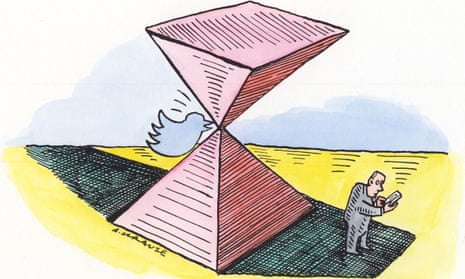

So you’re being followed by 2,000 or 20,000 people – now what? Experience teaches me that genuinely tending to the tweets of more than 200 people becomes impractical (and unenjoyable) unless you treat it as part of your profession. What this implies is a law of diminishing returns, with everyone sending out tweets few people have the time or energy to read or act upon. Essentially, Twitter, like the economy it is part of, is eating itself: it has become a social pyramid scheme whose enormous strengths are undermined by its own – our own – market-derived metrics, which tell us nothing about the quality of the experience. Indeed, in what terms do we value Twitter as an entity? Number of users. Stock price. The spiralling presence of marketers on Twitter is a symptom, not a cause, of its problems: an expression of the flawed global logic at its heart.

So, converting the world into numbers in order to process and make decisions about it: what does this remind us of? That’s right. We are becoming our computers. An idea that might sound shocking, but will come as no surprise to anyone familiar with the work of the media philosopher Marshall McLuhan, whose “the medium is the message” is the E=mc2 of societal motion. “We make our tools and then they make us,” he said.

Don’t we just. A few years ago, I wrote a book called Totally Wired, about Josh Harris, the first internet millionaire in New York, whose view of the web darkened as the 1990s progressed, until he found himself staging a series of extravagant happenings aimed at illustrating what it would do to us. “At first you’re going to like it,” he said, “but pretty soon you’ll find yourself fitting into smaller and smaller boxes and you won’t like who you are.” Essena O’Neill seems to feel the same way, so it could be that Harris’s predictions are about to come true.