On 25 August 1830, a riot broke out during a performance of

Daniel-François Auber’s La Muette de Portici in Brussels. The disturbance was carefully timed to start during the duet Amour sacré de la Patrie, and by the end of the performance, the Belgian revolution, ensuring the country’s eventual independence, had begun. Opera has brought people to the barricades, helped to overthrow monarchies and governments, and to end occupations and empires. Many of its composers believed, and still believe, in its ability to change the structures of society, and politicians in turn have believed in its potential for both ideological justification and propaganda. This week, our five operas take on the establishment, asking questions that are as relevant now as when they were written.

Mozart: Le Nozze di Figaro

Le Nozze di Figaro is so closely bound up with the mood and thought of Europe on the eve of the French Revolution that Georg Solti’s Paris performance, televised on July 14 (Bastille Day) 1980, seems in many ways the most appropriate choice for it. It features three of the greatest Mozart divas of of its day - Gundula Janowitz as the Countess, Lucia Popp as Susanna and Frederica von Stade as Cherubino - alongside José Van Dam’s spirited yet level-headed Figaro and Gabriel Bacquier’s brutally unpleasant Count. The production, by the progressive Italian director Giorgio Strehler, plays it very straight, but with quiet anger and a painstaking attention to detail. For something radically different, try Claus Guth’s 2006 Salzburg staging, in which the opera is re-invented as an internalised psychodrama that owes much to the films of Ingmar Bergman. It won’t be to everyone’s taste, but it’s wonderfully conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, while Bo Skovhus and Dorothea Röschmann realise the Almavivas’ marital hell more vividly than any other singers I know.

Beethoven: Fidelio

Jürgen Flimm’s 2004 Zurich Opera production of Fidelio sets Beethoven’s

only opera firmly during the Napoleonic wars, which were roughly contemporaneous with the period (1805-1814) of its composition. In evoking the political convulsion that accompanied its genesis, Flimm emphasises that the opera is not only a demand for freedom and individual dignity, but is also a reminder of the lengths to which we must sometimes go in order to achieve them. Camilla Nylund is the single-minded, self-controlled Leonore doggedly struggling to rescue Florestan (Jonas Kaufmann, in one of his greatest performances) from Alfred Muff’s sadistic, even Sadean Pizarro. Note how Rocco (László Polgár) and Jaquino (Christoph Strehl) are morally compromised by their collaboration, willing or otherwise, with Pizarro, while Marzelline (Elisabeth Rae Magnuson) is repeatedly in danger of becoming a casualty of Leonore’s quest. Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s conducting, meanwhile, is idiosyncratic but awesome.

Verdi: Don Carlo

Verdi’s name was synonymous in his lifetime with both the ideology and realisation of Italian independence, and his output as a whole constitutes opera’s most extended analysis of the conflict between the rights of the individual and the forces of church and state that seek to control them. His immense adaptation of Schiller’s Don Carlos, comparatively unsuccessful in his lifetime, is now regarded my many as the most comprehensive statement of his political concerns, though nothing in Verdi’s humanism is such that he is able to extend to the tyrannical figure of Philip IV of Spain the same compassion he extends to his effective victims.

The upload above is of the famous 1978 La Scala production, conducted at white heat by Claudio Abbado, with Plácido Domingo and Margaret Price sounding particularly glorious as Carlo and Elisabetta. The great Russian bass Yevgeny Nesterenko is the troubled, deeply affecting Philip, his compatriot Elena Obraztsova, in one of her finest performances, the majestic Eboli. Giorgio Strehler’s production abandons his more familiar naturalistic approach (as in Figaro, above) in favour of a series of slow, symbolic processionals that suggest the lives of individuals and nations caught up in the relentless progress of history.

Mussorgsky: Boris Godunov

Yevgeny Nesterenko in 1978, again, but this time at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, in a powerhouse performance as Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, the tsar who has murdered a child in order to obtain the throne, and whose mind and empire are both falling apart under the resulting psychological strain. He’s haunting and unforgettable - watch his death scene from 2:29:55 onwards if you don’t want to see the entire opera - as are Vladislav Piavko and the Soviet Union’s star mezzo Irina Arkhipova as the Pretender Dmitri and Marina. Rarely has the most insincere love duet in the entire repertoire - both characters are manipulators on the make - sounded so beautiful. The production has all the painstaking historicity of Soviet productions of the time, and every role is superbly taken - a reminder of what a great company the Bolshoi was in its heyday. Purists might object to the edition, which seems to mix bits of Rimsky-Korsakov’s version with Mussorgsky’s original, and has some cuts and re-orderings. Nesterenko, as far as I’m concerned makes it essential viewing: for a fuller text and a more modern take, with the opera updated to the 20th century, and the emphasis very firmly placed on the politics of revolution and regime change, try Herbert Wernicke’s 1998 Salzburg production, conducted by Claudio Abbado: you can watch it here.

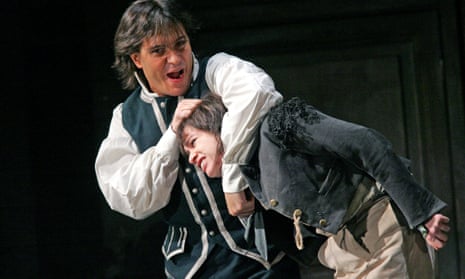

Britten: Billy Budd

The work of a gay man and a pacifist, Billy Budd is nowadays most commonly viewed as either a study in sexual repression or as an analysis of the metaphysics of evil. The narrative, however, deals with a miscarriage of justice in the British navy in the aftermath of the French Revolution, when fear of mutiny was at its height, and the opera inveighs angrily against a system that confuses law with genuine justice and fails to protect those it is ostensibly designed to help. The upload is a BBC production from 1966, made in the days when the Beeb regularly recorded operas in the TV studio. Directed by Basil Coleman and conducted, superbly, by Charles Mackerras, it features beautifully modulated performances from Peter Glossop as Billy and Britten’s partner Peter Pears as Vere. The real revelation, though, is Michael Langdon’s Claggart, tremendously sung and often quite disturbingly malign. Coleman makes a virtue out of having to confine the whole thing to a studio, and the shipboard atmosphere is very claustrophobic. The production was shot - as indeed the opera was written - at a time when sex between men was a criminal offence in this country. Most recent productions have made more of the gay subtext, though we still find it here in Langdon’s lingering gazes at Billy, and his hovering round his crew’s hammocks while they sleep.

Other fine interpreters of the title role include Peter Mattei, Bo Skovhus and Nathan Gunn. For a different take on the story, watch Peter Ustinov’s film of the Herman Melville story on which the opera was based: Ustinov himself plays Vere, opposite Robert Ryan’s Claggart, and Terence Stamp’s extraordinarily attractive Billy.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion