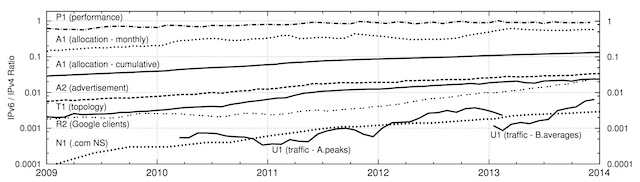

In a paper presented at the prestigious ACM SIGCOMM conference last week, researchers from the University of Michigan, the International Computer Science Institute, Arbor Networks, and Verisign Labs presented the paper "Measuring IPv6 Adoption." In it, the team does just that—in 12 different ways, no less. The results from these different measurements don't exactly agree, with the lowest and the highest being two orders of magnitude (close to a factor 100) apart. But the overall picture that emerges is one of a protocol that's quickly capturing its own place under the sun next to its big brother IPv4.

As a long-time Ars reader, you of course already know everything you need to know about IPv6. There's no Plan B, but you have survived World IPv6 Day and World IPv6 Launch. All of this drama occurs because existing IP(v4) addresses are too short and are thus running out, so we need to start using the new version of IP (IPv6) that has a much larger supply of much longer addresses.

The good news is that the engineers in charge knew we'd be running out of IPv4 addresses at some point two decades ago, so we've had a long time to standardize IPv6 and put the new protocol in routers, firewalls, operating systems, and applications. The not-so-good news is that IP is everywhere. The new protocol can only be used when the two computers (or other devices) communicating over the 'Net—as well as every router, firewall, and load balancer in between—have IPv6 enabled and configured. As such, getting IPv6 deployed has been an uphill struggle. But last week's paper shows us how far we've managed to struggle so far.

In an effort to be comprehensive, the paper (PDF) visits all corners of the Internet's foundation, from getting addresses to routing in the core of the network. The researchers also got their hands on as many as half of the packets flowing across the Internet at certain times, counting how many of those packets were IPv4 and how many were IPv6.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...