Thousands of young people rallied in Madrid to denounce the forced exile who are suffering from austerity policies. A generation are being forced to choose between unemployment, job insecurity or emigrating abroad. Betsabe Donoso/Demotix. All rights reserved.

Europe is facing deep and inter-linked political, economic, financial, constitutional and cultural crises, with the rise of xenophobic hate as well as high levels of unemployment, especially among young people, a betrayal of Europe’s post-war values. Rather than offer a new model to replace the chaos of the Westphalian system of nations, the EU itself is in chaos. Under such circumstances, do its media, old or new, properly hold Europe’s leaders, its institutions and decisions, to account?

The panel of speakers facing a packed sunlit courtyard on a Sunday morning in early October, this year, at the Internazionale Festival in Ferrara, mostly agree in one way or another that they do not. Hosted by Eutopia magazine, the session is chaired by Eric Jozsef, Eutopia’s Managing Editor, and on the panel is John Lloyd, Contributing Editor to the Financial Times and Director of Journalism at the Reuters Institute for Journalism, myself as an editor of openDemocracy’s Can Europe make it? debate, and Giuseppe Laterza, the Italian publisher who recently launched Eutopia.

John Lloyd opens the discussion by referring to the report he co-authored with Cristina Marconi, well summarized in the Eutopia article, Holding Europe to no account: a media question. Here the authors explain that it is hard to engage the general European public with the work of EU institutions at the best of times: except in crisis, the EU is boring, its decisions long drawn out, largely devoid of drama, hard to televise and unpopular.

I am uneasy about laying this problem at the feet of the European public. Take the UK for example. True enough, the US elections in all their onstage razamatazz have been more of a regular media feature in our lives than the European elections, including last May’s. We have come to take this for granted.

But what might have made a difference? A public debate over the effectivity of austerity as the EU-wide policy that it is? We have had nothing like that in the UK. The closest we came was the recent mass lynching of the Labour party leader by the Westminster circus and its media for forgetting to pay due lip service to the priority of cutting the national deficit in his speech to Labour Party conference. The three mainstream parties have signed up to a pact to mention this in all major speeches, as if they think the British public might otherwise begin to wonder if there was an alternative. It is big news if someone breaks rank, even inadvertently – surely a lamentable example of missing the wood for the trees!

On the other hand, this is a debate you can access in Can Europe make it? Here was Frances Coppola, of the FT, writing for us in the week of the festival:

“The connection between long periods of fiscal austerity and the rise of far-right nationalist parties is well established – the early 1930s in Germany is a good example…. I fear that, because of the unholy alliance between those who want closer European union and those who want tight money and mercantilism across the whole of Europe, Europe is heading for the rocks. And this ship is not for turning.”

Whatever one thinks, this prognosis is surely not boring for Europeans? Complex, maybe: but hardly devoid of drama or personality. And yet, as the author says herself, this argument too will essentially fall on deaf ears.

True it is not what Europe’s powers that be want aired. But more than this, if Europe is largely invisible today, this is because of the cultivation over time in many if not most of our democracies, of a certain type of politics which increasingly has Europe in its thrall. A process of ‘majority reassurance’ coupled with enemy images of the foreign, has undermined solidarity both within our societies and across Europe. In this democratic sleight of hand that passes for governance in an age of globalization and financial crisis, the traditional media is not a passive victim. They do most of the spade work.

The 'National Us'

At its most populist, the only game in town is the reconstruction of a nostalgic, idealized, monocultural ‘National Us’ – a little rechristianization of Italy here, re-laicisation of France there, the prime ministers of Germany, Spain and Britain all confirming that multicultural societies ‘don’t work’, governments adopting an increasingly anti-immigrant stance, and Great Britain, of course, heading for Brexit. From this perspective, nothing much exists beyond one’s own borders that is not threatening. Only a strong and selfish national government can save you from whatever it is. This is the ‘common sense’ of our times and the right wing populist parties, plus a certain kind of separatist movement, plus the anti-Europeans, far more than the political mainstream, increasingly benefit from its narrative monopoly, aided and abetted by the tabloids and popular tv.

If you only read the headlines when you walk past a newsstand in Britain, there is no good news about Europe to be had, just as there is none on immigration, but a drip-drip-drip effect that after a while, must influence your point of view. After a while, the EU disappears, except as John Lloyd says, ‘as a chamber which each nation can blame when something goes wrong’ - as it increasingly does.

But if it is knockabout that we want, a trend to watch must be the rising presence of the EU’s 140 out of 751 so-called ‘populist’ MEPs - who while not at all a united force - are likely to become a loud, disruptive voice in the European parliament. Not too inclined to waste much time on the core co-decision work of European Parliamentary committees, they will nevertheless happily address their remarks directly over the heads of the EU to their respective fan bases. And with Marine le Pen topping the presidential polls in France, we may soon be wishing for a little more boredom.

No, I don’t think we can lay this problem at the door of a mistaken European public. ‘Europe’s credibility crisis’ on which our tabloid press and popular tv are quick to report, is surely real enough. What these media don’t tell you, because it doesn’t suit them, although they cover themselves with a certain all-pervasive cynical tone, is that this is a crisis in governance as we know it, and not just the European variety.

When many Europeans voted against the Establishment in May, we can be quite sure that we were dealing with a protest vote directed at governance in general - a popular discontent, not at all misplaced, that has its roots in dissatisfaction with the widening gap between people and the political class tout court. The crisis of governance I am talking about is the absence of convincing representation and interaction. One particularly stark instance of this is the whole exercise of building Europe, in which the people have been pretty comprehensively left out. And this, I want to argue, is where new media comes into the equation.

New media in Europe and several new types of invisibility

Of course, new media are not going to fix the notorious problem of the European democratic deficit. Indeed, despite unprecedented efforts made by EU institutions to communicate in the last elections (including some new media efforts in advance of many member states), there is a mutual disconnect between European institutions and users of new media that is even more profound.

But the challenge here is rather different from those presented by the obscuring vistas of the National Us. New media was well described by David Sifry in a survey for the Economist a decade ago, as the ‘conversation’ that has broken out between people ‘formerly in the audience’, and this space of much more complex flows of laterally scaled belonging poses a historic challenge to the traditional conception of a ‘public’, both to the EU and to governance in general, that is not going to go away. The reason for this lies in the very nature of the beast.

Of course there are many excellent online sites which offer European debate and debate on Europe – we have the RSS feeds of some of the best on our Can Europe make it? pages. But, whereas in my day, people might identify themselves as readers of the Guardian, the Economist or the Financial Times, now my young co-editors are not going to rely on a single source of information. They would rather use social media (e.g. Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter) to read the news recommended by friends, or the people they follow (who can be politicians, celebrities, but also family members) or, look at the links on Reddit shared by members of the same 'subreddit', or community of interest.

As much as in the past, this is an identity-defining process. But much less in the hands of journalists and editors who create news to fit their outlets' broad orientation, and more than ever in the hands of readers who will make up their own mix to reflect their interests and the image of themselves they seek to project. Take the Europe subreddit – a sort of polis of ideas – a particularly good example of debate without an editor in sight – with a stream of information accessed from all over the net, filtered by communal consensus and personal preference. Have a look at EU Citizens: what is your honest opinion of the European Union? on the Europe subreddit if you haven’t already – it’s pretty good.

One important feature of this type of ‘conversation’ was well articulated by Steven Weber, also in 2004, when comparing open source to modern religious communities. He said that: “ It is the leader who is dependent on the followers more than the other way around… the primary route to failure for them is to be unresponsive to their followers.” In this case, the leader is anyone who wants to start an online discussion.

Secondly, poll after poll shows that young people are more informed today than ever. Why so, if like their forebears, they will see headlines and summaries of articles appearing on their Facebook feed without actually reading the pieces in full? What they do ingest on the web today is pluralist content, a wide availability of sources, and many angles on every issue. Social networks are an excellent way of getting the news that matter to all your circles of friends, whatever their geographic origin or location. People have to make choices about what they believe all the time: they are not passive consumers any more.

So for example, both my editors use and admire the Europe subreddit. As my Greek editor puts it: “I like the decentralised, user-oriented, democratic feel of reddit as you actually feel that you are engaging in a real, horizontal, non-hierarchical debate as opposed to one structured and moderated by a traditional and distant media outlet.” But he was also particularly keen on Guardian coverage of the rise of Marine le Pen’s influence in different regions of France, while my Czech Swiss editor, now in Lebanon, where his Facebook page gets news posted regularly by friends from there as well as the US, UK, France, and Switzerland, is currently interested in Github – a collaborative software programming platform which he says he could well imagine being the inspiration for a new type of 'social' law-making in the EU.

In short, the new culture that is developing in the digital commons is transnational, more egalitarian, more transparent to its users, less deferential, more diverse and above all, self-authored.

So, if you are looking for a debate on Europe from the point of view of old media - those one-way hub-to-spoke structures running from a high cost centre to cheap, reception-only systems at the periphery, with no communication between end points and no return loops to send observations back to the core – it is likely to be so disaggregated as to be rather invisible, and always going on somewhere else. There is an important analogy here I think with the old politics, those one-way forms of political representation that simply no longer represent increasingly articulate and diverse populations, the people, ‘formerly the audience’, who wish to collaborate, to have meaningful lives, and to make a contribution to that ‘conversation’.

This has many implications for those of us who are working in new media, and also for the political institutions. For the time being, any encounter between the European Union and this kind of empowered community is likely only to throw into further relief the absence of a meaningful people power. There is much evidence of this gathering sense of disconnect, but take two recent examples from openDemocracy:

1. First Puzzled by Policy? as interviewed recently in our feature, ‘Participation Now’. This is a European Commission-funded online e-participation platform to facilitate citizen involvement in the policy-making process, that has been working on migration policy in Hungary, Italy, Spain, Greece for three years. They are trying to foster the involvement of citizens when there’s a low level of trust.

The policy makers did want this feedback, but they and the project soon came up against a fundamental problem: where actually does feedback fit into traditional policymaking processes based on expert opinion? You are in a chicken and egg situation: you need the policymakers and politicians to confer legitimacy on the whole process, guaranteeing that the time and effort people put in will be effective. But the politicians and policymakers require a critical mass of users before it is ‘worthwhile’ committing their time. That can’t happen overnight.

It’s the same on openDemocracy. Whoever wants an audience on our platform for their ideas has to build concentric circles around the original group, translating out their ideas for a wider audience. But at each stage, what you do know is that you can’t instrumentalise people – there must be something tangible in it for them, otherwise it won’t work.

2. Or take Halldor Svansson, the first Icelandic Pirate to sit in a majority coalition as a city councillor in Reykjavik today, who at 34 years of age chairs the committee on Administration and Democracy. He thinks the political class simply doesn’t understand the impact of smartphones on the inherent complexity of the horizontal spaces of public communication. But he also thinks that the initiative, to reconnect, has in part to come from the politicians themselves…saying, ‘we don’t want to rule on our own’. That’s why he is willing to live in a half way house, and try and change things from within. His problem is that he knows full well, IT seen as ‘cosmetic’ won’t be trusted. People want in.

In the same way that citizens are interacting with all aspects of their life, shopping, banking and so on, it will come to be expected in politics as well that more public services are available online and that there’s more interaction. Svansson and his colleagues in Iceland see social media and e-democracy as the two faces of the same coin, mechanisms to inform, organize and engage with policymakers - but they know they have to make a difference.

So far, these 'cosmetics' are used only to show a modern face to the world when the institutions themselves are outdated. For now, policymakers and politicians and citizens speak different languages… neither seeing the other. It is difficult to translate people’s issues into policy at the other end. Perhaps this will be the particular skill set of a future type of democratic politician, using the new media.

Something else is happening

However, if the cosmetic use of IT by existing institutions isn’t going to work, this doesn’t at all mean that nothing is happening. What it does mean is that when it happens it comes as a big surprise, every time. Look at the rejection of the ACTA treaty in the European Parliament. Did Timothy Garton Ash, who runs the Free Speech Debate see that coming? No. “Who would have thought ACTA would be one of the biggest mass movements in Poland in the last ten years? And intellectual property rights the biggest mass mobiliser on free speech issues of the lot!” Then there is the widespread use of internet-mediated political action in the Spanish and Turkish and other uprisings. Let’s add to this the Scottish referendum. A fantastic nationwide debate which led to more than a 90% turnout in the referendum, driven by a vibrant Yes campaign in the new media… Again – a big surprise to the status quo.

Philippe Agrain on Eutopia has drawn up a list of these new social movements which he rightly says are all the more powerful and attractive because they combine radical political reform with the commitment to the building of a better daily life. How have the present European post-democratic leaders responded to such initiatives? He points out, by stigmatising and surrounding them in an ever more hostile regulatory framework. So to return to our opening question, maybe we have to conclude that at a profound level, Europe today opposes the prefiguring of a genuine European demos.

Our European coverage?

Where does openDemocracy fit in? We’d situate ourselves firmly in that other halfway house that Jeremy Rifkin describes as a “hybrid economy, part capitalist market and part Collaborative Commons”. We adopted ‘creative commons licensing’ in 2005 and we see oD as a digital commons, not a commodity but a shared resource; an independent, public interest space, and a counter to the corporate media.

We publish around 70 articles a week, receive over half a million visits every month, and are read in every country on earth. Our content is frequently cited, cross-posted and re-published globally. Our archive contains over 25,000 articles. Our readership shows strong growth across the world – a 63% rise in visits this year compared to last - and is very diverse. It includes many who regard themselves as “influencers” - scholars, journalists, activists and policy makers.

Social media is “our new front page”. openDemocracy has over 37,000 followers on Facebook and 25,000 on Twitter. Of all our visits, over 20% now originate from social sharing. The front page and our editorial recommendations are much less of a driver than once they were. Nowadays, rather than telling people what to read in some centralized fashion, what is proving successful is the practise of growing themed hubs, centres of interest, with their own oD audiences - a set of diverse, but altogether longer-term relationships.

In 2011 we began to build another of these, Can Europe Make It? (CEMI), with its own front page, social media promotion, Facebook page, and e-mail, to address what we thought of as the absence of a demos. We built our page as a huge question mark hanging over the vacuum embracing most Europeans, caught between remote EU institutions and subterranean Europe, between Reinventing the Left and Tributaries of the Right. We wrote: “This is a page aimed at the millions of Europeans who are puzzled about where to turn for an explanation of Europe’s multiple crises, let alone some redress. No longer relying on the political Establishment, we hope that together, we may begin to formulate a way out of the impasse which afflicts our continent.”

We came up with our ‘Joining the dots’ feature, to track European deep structure across its national silos, for example, on Football and Politics, on The surveillance state in Europe or of course, The media; and we combine this with our ‘Spotlight on’, e.g. Spain and Catalonia, or the Icelandic constitution, having discovered the paradox that the more ‘local’, intimate and knowledgeable our coverage is, the more the rest of us find we have in common with it. For the Euro-elections, we decided to pretend that there was a European demos and that it is possible to have a transnational debate… and put this theory to the test by creating our own mini-European ‘You Tell Us’ forum for 15 young bloggers from across the continent. Many of them found it a “life-changing” experience, and we were rewarded with refreshing writing on precarity, political apathy, the rise of the far right and migration, and European democracy, in what is our single best-read feature so far.

Can Europe Make It? has grown significantly since 2011, and now publishes around 1/8 of the openDemocracy output. We saw a tripling of visits last year, 80,000 visits in September, and growth in readers from all European countries, whose stay on these pages is longer than anywhere else on openDemocracy. Visits from Turkey have doubled to 100,000 since May 2013 - as openDemocracy covered the Gezi Park demonstrations and Turkish presidential elections. Facebook fans from Italy, Spain, Turkey and Greece are particularly numerous. In 2014, oD was nominated Citizen Media of the Year for the European Democratic Citizenship Awards, and eminent commentator Ulrike Guerot recently said of us: “ a unique outlet, open to unorthodox views and committed to fostering a genuinely democratic exchange on how to save our storm-tossed continent.”

Can new media hold Europe to account?

This timely discussion comes at a point when we all have good reason to get to grips with two large and complex phenomena and their interaction – the European Union, and the peoples of Europe. For the latter, not just in Scotland, I am convinced that there is a huge, lurking potential for engaged electorates to ‘come out’ of the woodwork, if they think they can make a difference to European developments - not just the usual propaganda, pro and contra Europe.

As for the EU, here are three of the stories Can Europe make it? will be covering next, in our own attempt to hold Europe to account. All are starkly characterized by a disinclination on the part of our leaders to let those ‘formerly in the audience’ onto the world stage with a measure of self-determination over their lives.

First, there are the controversies over TTIP – the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, and a whole series of chaotic attempts by the EU presidency to rush through 'secret courts' for investors to sue governments who try to protect their citizens and public services. Across Europe there is mounting outrage against the idea that public courts aren’t good enough for corporations, and that they should enjoy a parallel, secret and hugely powerful legal system of their very own. Moreover, when ‘Stop TTIP’ - an alliance counting over 240 organisations from across Europe - tried to use the new mechanism set up by the Lisbon Treaty of the European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) to repeal the negotiating mandate for TTIP, this “major improvement" of the “democratic life of the European Union” was refused them. Their response?

“Democracy arises through social intervention and participation in the political process; it is not something to be granted or denied by Brussels. That is why in early October, we will be launching a self-organised European Citizens’ Initiative. The European Commission is trying to ignore us; we will ignore the European Commission. And of course we´ll challenge the Commissions´ decision at the European Court of Justice.”

Our second project deals with an unprecedented, fundamental attack on our civil liberties and collective freedoms, which would have remained unknown were it not for Edward Snowden. Our Europe-wide feature, Closely Observed Citizens, monitors the emerging surveillance state and the fightback in the courts by some of the very same EU governments who seem so eager to join this new Five Eyes club. Those of our European representatives who are fighting this new authoritarianism to protect the rights and privacies of European citizens would like us to recognize the unique platform for the fightback which the EU provides. But will they be able to win the trust and support of those European citizens, before the chill factor turns us into frightened suspects, one and all?

Thirdly, we have a partnership on Precarious Europe: three young editors setting out from Scotland, Bosnia and Italy, gathering the stories of those who don’t have a loud enough platform or the necessary skills to blog, finding out how they are organising themselves, against a background of 22.5 per cent youth unemployment across Europe ranging from Germany’s 7.6 per cent to Greece’s 59%. These levels of unemployment are one more hostile act against a civilised European future, and under all these conditions, old or new media, we must surely find a way to hold our politicians and their leaders to account.

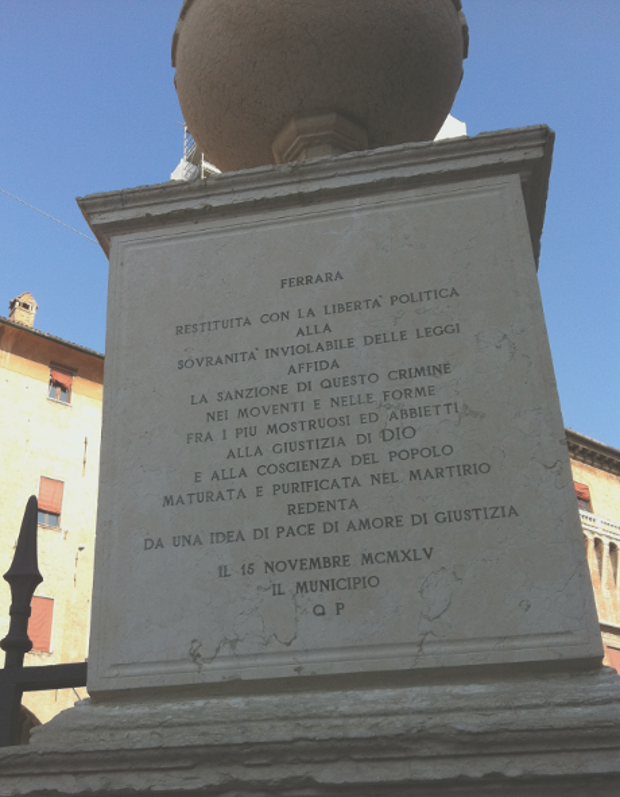

Monument at Ferrara Castle

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.