John Paul Getty’s formula for success was to rise early, work hard and strike oil. But a dependence on the black stuff can create its own problems, especially when the price tumbles as it has over the last few months.

The price of a barrel of Brent crude has almost halved from $115 in the summer to stabilise around $60 last week. Most forecasters expect the cost of oil to remain low well into next year.

Getty became a billionaire oil magnate after four years of speculative drilling in the Saudi Arabian desert proved to be worth the risk. Now the house of Saud appears willing to wait almost as long for its own victory. The plan, agreed with Opec, maintains output, ignoring demands for cuts to push the price back up again.

As the dominant Opec member, and keen to protect its own market share, the Saudis have forced the others to take the long view with a strategy that aims to put out of business all those producers that have flooded the market in the last few years and dragged the price lower.

US fracking firms, where production costs are high, should be the first to feel the financial pain. But there will be collateral damage to others too. Iran may find itself running out of cash. And then there is Russia, which is heading for a deep recession next year as gas prices follow oil to lows not seen in 10 years. There will be winners too. The UK, now a net importer of oil, has already benefited by an estimated £3m-a-day reduction in fuel costs. Businesses will gain from cheaper energy, and cheaper petrol in effect puts more cash in consumers’ pockets.

Taken in the round, global GDP could rise by 0.2% to 0.5% as the wheels of trade are lubricated a little more.

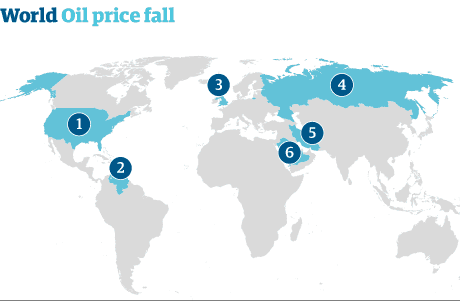

1. The US

There is a popular theory that the US wants to see oil prices low for some time to undermine Vladimir Putin’s ambitions in eastern Europe, put pressure on Iran and spur a global economy desperately in need of cheap energy. In the US alone, each $10-per-barrel drop in the price of oil boosts GDP by 0.1%, according to Swiss investment bank UBS.

Fracked oil and gas across the central plains of the Dakotas, Kansas and Nebraska, coupled with oil from Canadian tar sands, has slashed demand for oil imports to the US – resulting in the world market for oil and gas being flooded. Alongside rising supply is waning demand, especially as Japan looks to switch back on its nuclear power stations and China’s manufacturing sector growth slows.

Yet a prolonged period of low prices could put the entire fracking industry out of business. Frackers have a break even point of $110 a barrel or above and have few resources to maintain uneconomic production.

Frackers have pushed output from 5m barrels a day in 2008 to 8.5m in June this year. Gas production is up by a third since 2005. One US academic estimated that one shale find in south Texas added $87bn to the US economy in 2013. The closure of one well after another, which is already happening, is not therefore something the White House can ignore.

2. Venezuela

Only a couple months ago, a standard Barbie doll sold for about $200 in Venezuelan shops. In the runup to Christmas she can be bought for as little as $2.50, while stocks still last, following President Nicolas Maduro’s bizarre effort at subsidising festive consumerism.

Worse, the cash used to buy Barbies will soak up much of the country’s foreign currency, already depleted after years of corrupt import scams and now the falling oil price.

One of the worst-hit members of Opec, Venezuela has a oil price beak-even point of $117 a barrel. Such is the inefficiency of its industry and the profligacy of its government that some industry experts expect it to run out of money next year. Instead of Father Christmas, Maduro may then have to turn into the Grinch, imposing even greater levels of austerity on an already beleaguered nation.

3. UK

In 2005 the UK became a net importer of oil, complicating its relationship with a source of bumper revenues over the previous 25 years. The recent fall in the oil price helps the balance of payments and gives a price cut to consumers worth £3m a day, but it hits an industry that keeps much of Scotland’s west coast in employment and provides the exchequer with significant if declining tax revenues. The boss of Wood Group, an oil engineering firm, said 15,000 jobs could go next year as output drops to 800,000 barrels a day. Nicola Sturgeon, Scottish National party leader, is likely to be recalibrating her stance on North Sea oil as a secure base for the finances of an independent Scotland (her predecessor, Alex Salmond, based his economic rationale for independence prior to the September referendum on oil at $113).

Such is the power of fluctuating oil prices to influence economic decision-making that it was mentioned last week as not only putting extra pounds in shoppers pockets for Christmas spending, but also depressing the inflation rate to the extent that Bank of England officials must delay interest rate rises scheduled for next summer.

4. Russia

President Vladimir Putin dismissed concerns at his annual press conference last week that Russia could default on its debts should oil prices remain low next year. But he was kidding few that Russia can prosper with prices at $60. Russia’s parliament recently approved a three-year budget that assumed an oil price of $100 a barrel in 2015-17.

The finance ministry now expects oil to trade at $80 next year, and the economy to contract by 0.8%. Budget revisions are ruled out. Nevertheless, with oil and gas accounting for 70% of exports and 50% of tax receipts, anything less than $100 a barrel will mean big budget cuts and far deeper recession.

It looks as if infrastructure spending will be sacrificed to protect welfare and defence budgets – with the incursion into Ukraine aiding the armed forces’ demand for a 30% budget boost.

Russian companies that borrowed from western banks are also in trouble. The corporate sector tapped the west for cheap credit and must pay the interest on the loans in dollars at a time when a collapse in the rouble means dollars are more expensive. Oligarchs have lobbied Putin to help pay their loans. So far the president has said no, preferring to rely on the central bank defending the rouble by pushing interest rates to 17%.

5. Iran

As one of the targets for both Saudi and US foreign policy, Tehran is in a bind. The government has increased spending to placate its westernised middle class at the very moment US sanctions and the low oil price are both eating into its budget. The US hopes that a deal is possible limiting Iran’s nuclear ambitions while the Saudis want an end to Iranian-funded jihadis in the region. The first is possible and the second unlikely, but cash-for-terrorism could be more circumscribed following a prolonged period of low oil prices.

6. Saudi Arabia

The desert state has amassed a $1trn war chest to see it through periods of lower prices. Only last week a clearly relaxed finance minister Ibrahim Alassaf said his 2015 budget would go ahead despite “challenging” global economic conditions.

Alassaf has championed the kingdom’s “counter-cyclical” fiscal policy, which helped build up a mountain of foreign assets when oil prices were high. So while the world’s top oil exporter is believed to need an average crude price above $90 a barrel to balance its budget, and a first budget deficit since 2009 will involve the sale of foreign assets to balance the books, it can survive for many years at $60 a barrel.

And why would it do this? To limit the global production of oil and gas over the longer term, especially fracked oil and gas in the US and Europe, which have previously depended on Middle Eastern supplies. And, like the US, it wants to bring Iran to heel.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion