The first question Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg was asked at a company Q-and-A last week was whether he’d ever consider adding a “dislike” button. He didn’t say no. Instead, he kicked off his response by saying, “We’re thinking about it.”

Let me attempt a rough translation of what Zuckerberg meant by that: “Why yes, tech reporters and news anchors of the world, please do flood the airwaves and Internet with 11 million fluffy ‘what-if’ stories about my company on this slow news day in December.” It was, in other words, a canny answer from a publicity perspective. But was it true? Is Facebook really thinking about adding a dislike button?

The short answer is “no,” for reasons that run deep in the company’s DNA—and that Zuckerberg would be loath to explain honestly. But the way Zuckerberg answered the question is surprisingly revealing—and troubling, coming from perhaps the most influential man in online media today. And it helps explain why Facebook is so much more conducive to baby photos, viral hoaxes, and false cheer than it is to intelligent discussion of news and ideas.

Zuckerberg’s full response is in the video below, and well worth watching if you want to see a powerful billionaire attempt to explain how something that’s clearly in his own company’s economic interest is actually in the interest of humankind at large.

The key lines are these:

Some people have asked for a dislike button because they want to say, “That thing isn’t good.” And that’s not something that we think is good for the world. So we’re not going to build that.

That’s actually a pretty clear response—if a somewhat disingenuous one, as I’ll show. But first, what is Facebook thinking about building, if not a dislike button for people who dislike things? Zuckerberg didn’t say, exactly, but he did drop some clues.

When people share “sad moments in their lives,” or “tough cultural or social things” on Facebook, Zuckerberg said, others don’t always feel comfortable pressing “like.” To address that, he went on, the company has been exploring ways for users to easily convey emotions like surprise, laughter, or empathy. That’s consistent with past reports that Facebook has experimented with a “sympathize” button that could appear in place of the like button on sad, angry, or downbeat posts. But Zuckerberg noted at the end of his response that “we don’t have anything coming soon.” That makes sense: Facebook’s algorithms are intelligent enough today to discern a happy post from a sad one most of the time, but not with 100-percent accuracy. (It’s also perfectly fine in most cases to hit the like button on a friend’s post when sympathy is your real intention.)

What’s really interesting about Zuckerberg’s comments is not the substance of his answer, but the way he justified it.

Here’s what he didn’t say: A “dislike” button on Facebook would dissuade people from posting, liking, and sharing as freely as they might otherwise. For a company that trades in data about users’ behavior, more behavior is almost always better. Its algorithms optimize for “engagement,” which includes posts, likes, clicks, shares, and comments. Among the metrics Facebook does not optimize for: honesty, exchange of ideas, critical thinking, or objective truth.

Seeing dislikes on other people’s posts might dissuade you from mindlessly liking them yourself. Seeing dislikes on your own posts might make you think harder about what you’re sharing. Either way, it’s a barrier to engagement and, as such, an impediment to Facebook’s growth.

And just imagine how the brands that pay Facebook’s bills would feel about seeing dozens, hundreds, tens of thousands of dislikes on their own posts. Zuckerberg would have a lot to answer for on his next earnings call with investors.

All of these are legitimate business reasons for Facebook to keep shrugging off calls for a dislike button, although there might be ways around each. (For instance, the dislike option could be disabled on posts by brands, and there could be an option for users to disable it on particularly sensitive personal posts.)

But again, these aren’t the reasons Zuckerberg cited in his Q-and-A. Instead of talking about why the dislike button would be bad for Facebook, he insisted it would bad for society at large. He literally said that giving Facebook users a way to disapprove of the site’s content is “not something we think is good for the world.” Later he added that if Facebook ever does add buttons for emotions other than liking, the company would “need to find out the right way to do it so [it] ends up being a force for good and not a force for bad.” Can’t wait for the A/B tests on that one.

One way to view this is that Zuckerberg is simply bullshitting us. He knows this is really about Facebook’s financial interests, but he understands that would sound unseemly, so instead he feeds us bromides about what’s good for the world. If so, then fine: No one really expects a CEO to be totally frank about his company’s motivations.

The more worrisome possibility is that, on some level, Zuckerberg actually believes what he’s saying. This would imply one of two things: One possibility is that he has become so wrapped up in his company’s mission—to “make the world more open and connected”—that he sees any obstacle to its continued growth as bad for humanity. That sort of false identification of one’s self-interest with the interests of everyone else can lead to grandiosity and a conviction that the ends justify the means. It’s pretty standard-issue in Silicon Valley.

The other possibility is more mundane but no less worrisome. It’s that Zuckerberg fails to appreciate the critical roles of conflict and disagreement in a free society—that he believes we’d all be better off if we were impeded from expressing negative sentiments. “If you don’t have something nice to say, don’t say anything at all” is an admirably mature stance—for a first-grader. In a man who has become perhaps the most powerful force in media, it’s quite the opposite.

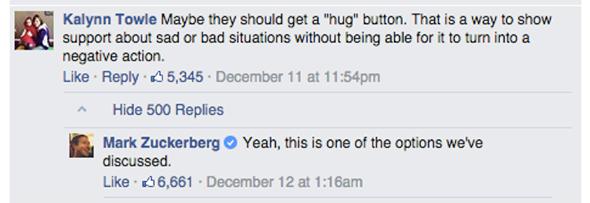

This matters because Facebook has become the largest driver of traffic to news and opinion sites around the Web. And because its algorithms are more influential in determining what people see than any editor on the planet. And the like button now influences not only the distribution of news, but how it’s produced and framed. (No media entity is ignorant of the fact that headlines conducive to Facebook sharing are likely to help its bottom line.) It’s part of the reason that, at a time when Twitter was ablaze with debates about race, the use of force, the militarization of the police, and the rights of protesters in a democracy, Facebook was drowning in ice bucket challenges. One sees itself as a forum for real-time news and commentary; the other thinks the best alternative to a like button might just be a “hug” button.

Screenshot courtesy of the author

According to Facebook, at least 6,661 people like that idea. How many people dislike it? We’ll never know.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.