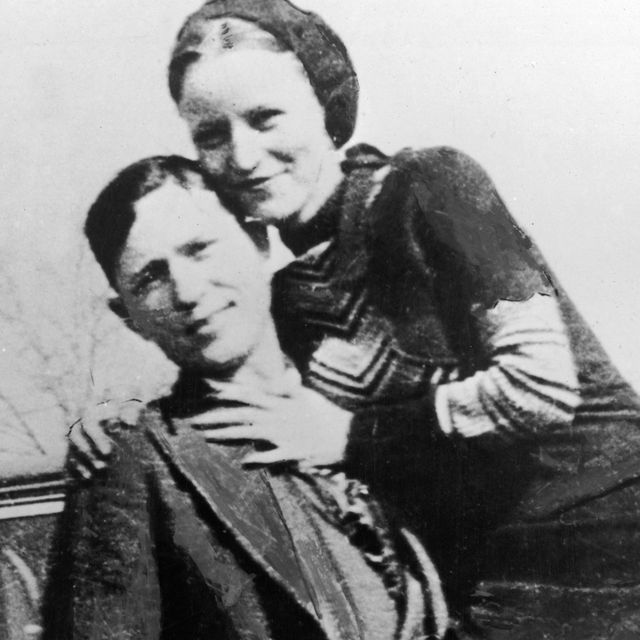

Possibly the most famous and most romanticized criminals in American history, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were two young Texans whose early 1930s crime spree forever imprinted them upon the national consciousness. Their names have become synonymous with an image of Depression-era chic, a world where women chomped cigars and brandished automatic rifles, men robbed banks and drove away in squealing automobiles, and life was lived fast because it would be so short.

Of course, myth is rarely close to reality. The myth promotes the idea of a romantic couple in stylish clothes who broke the bonds of convention and became a threat to the status quo, who didn't fear the police and lived a life of glamorous luxury outrunning them. The reality was somewhat different. Sometimes incompetent, often careless, Bonnie and Clyde and the Barrow gang lived a hard, uneasy life punctuated by narrow escapes, bungled robberies, injury, and murder. They became one of the first outlaw media stars after some photos of them fooling around with guns were found by police, and the myth-making machine began to work its transformative magic. Soon fame would turn sour and their lives end in a bloody police ambush, but their dramatic and untimely end would only add luster to their legend.

While the longevity of the story of Bonnie and Clyde may be more of a testament to the power of myth and media than to the couple’s actual attributes, there is no question that their story continues to fascinate writers, musicians, visual artists and filmmakers.

We explore nine facts about the real Bonnie and Clyde that you may or may not find in movie versions of their story.

Bonnie and Clyde became famous, but not for what they had hoped

As a boy born into the family of a poor farmer, Clyde “Bud” Barrow’s great love was music. Bud loved to sing and play an old guitar on the farm. He taught himself how to play the saxophone, and it seemed as if he might pursue a career in music. Influenced negatively by his older brother Buck as well as a shady friend of the family, however, it wasn’t long before young Bud’s interests turned from playing songs to stealing cars.

Little Bonnie Parker also loved music growing up in west Texas, and she also loved the stage. She performed in school pageants and talent shows, singing Broadway hits or country favorites. Bright and pretty, she told friends that they would see her name in lights one day. She was a big movie fan and imagined a future for herself on the silver screen.

Fame would come to both Clyde and Bonnie, but not as they had envisioned. Bonnie would eventually appear on the screen that she dreamed of, but only as part of newsreel reports detailing the exploits of her and Clyde’s criminal misadventures. Their fame spread through (often inaccurate) reports of their criminal activities in local newspapers and true crime magazines. Although they at times reveled in the attention, most of the time it made their lives more difficult since they could be more easily recognized by larger numbers of people.

Clyde and Bonnie never quite surrendered their dreams. Bonnie’s movie magazines were usually found left behind in the stolen cars that police recovered, and Clyde carried his guitar until he had to leave it behind during a police shootout (he later asked his mother if she would contact the police to see if they would return it; they said no). Clyde loved music right up until the end—found in Bonnie and Clyde's ambushed “death car” was his saxophone.

Bonnie and Clyde didn’t spend much time robbing banks

Movies and TV have tended to portray Bonnie and Clyde as habitual bank robbers who terrorized financial institutions throughout the Midwest and south. This is far from the case. In the four active years of the Barrow gang, they robbed less than 15 banks, some of them more than once. Despite the effort, they usually got away with very little, in one case as little as $80. The few successful bank robberies associated with Bonnie and Clyde were mostly committed by Clyde and criminal associate Raymond Hamilton. Bonnie would sometimes drive the getaway car, but often she was not involved at all, staying at a hideout while the rest of the gang robbed the bank.

Banks were a complicated proposition for Bonnie and Clyde, and when they were on their own, they rarely attempted bank jobs. They more commonly robbed small grocery stores and gas stations, where the risk was lower and the getaways easier. Unfortunately, the “take” from these kinds of robberies was also usually low, which meant they had to perform robberies more often just to have enough money to get by. The frequency of these robberies made Bonnie and Clyde easier to track, and they found it more and more difficult to settle anywhere for very long.

Bonnie didn’t smoke cigars

The most famous picture of Bonnie shows her holding a pistol, her foot up on the bumper of a Ford, a cigar clamped in her mouth like Edward G. Robinson in Little Caesar. This is part of a collection of comic photographs clearly made for Bonnie and Clyde’s own amusement. They were found on undeveloped film that was abandoned at the gang’s Missouri hideout when police attacked the house. In one picture, Bonnie points a rifle at Clyde’s chest, as he half surrenders with a smile on his face; another picture shows Clyde kissing Bonnie in exaggerated movie-star fashion.

These photographs, as well as Bonnie’s poems, also found at the hideout, were largely responsible for making Bonnie and Clyde famous. Newspapers all over the country reprinted the cigar picture. All evidence shows, however, that Bonnie was a cigarette smoker like Clyde (Camels seemed to be their preferred brand). The mythic image of Bonnie as a mean mama puffing away on a stogie is just that: an image. On the other hand, Bonnie liked to drink whiskey, and several eyewitnesses from the time remember seeing her drunk. Clyde shied away from alcohol, feeling that it was important for him to be alert in case they needed to make a fast getaway.

Bonnie died a married woman – but not to Clyde

Not generally known is the fact that Bonnie got married when she was 16. Her husband's name was Roy Thornton, and he was a handsome classmate at her school in Dallas. The decision to marry was not hard for the young girl to make; her father was dead, her mother worked a hard job at a factory, and Bonnie herself had little prospect of doing much else but waiting tables or working as a maid. Marriage seemed like a way out.

The marriage was a disaster. Unbeknownst to Bonnie, Roy was a thief and a cheat; she referred to him later as a “roaming husband with a roaming mind.” He would disappear for long periods of time, and when he returned he would be drunk and abusive. Bonnie took to sleeping at her mother’s. Eventually, one of Roy’s schemes backfired, and he ended up with a five-year sentence for robbery. He was still in prison when he heard of his wife’s death in the company of Clyde Barrow.

Bonnie died with her wedding ring still on her finger. Divorce was not really an option for a known fugitive.

Bonnie and Clyde both had trouble walking

Convicted on multiple counts of stealing cars and robbing stores (as well as one jailbreak), Clyde was sentenced to 14 years at Eastham Prison Farm, a notoriously harsh hard-labor penitentiary, in 1930. Clyde only served a year and a half of his sentence thanks to his mother, whose pleas to the governor of Texas resulted in Clyde’s parole. In those seventeen months, however, Clyde had been starved, violently abused by guards, and raped repeatedly by another prisoner (who he eventually stabbed to death, with one of Clyde's “lifer” friends accepting responsibility for it).

Unable to take “the bloody ‘Ham,” as it was nicknamed, Clyde decided to hobble himself in order to escape the difficult work detail. Using an ax, he or a fellow inmate chopped off two toes on his left foot. Little did he know that his mother’s plea would be successful six days later. Clyde’s balance was never the same, and his walk was slightly hobbled from then on. He also had to drive in his socks, since he couldn’t balance correctly on the pedals of a car while wearing shoes.

Clyde was driving in his socks in the summer of 1933 when Bonnie would suffer an even greater injury. Clyde, known for his reckless fast driving, did not see a “detour” sign for a road that was under construction. He missed the turn and plunged down into a dry riverbed. The shattered car battery spurted acid all over Bonnie’s right leg. Bonnie was carried to a nearby farmhouse, and only the quick application of baking soda and salve stopped the burning away of her skin and tissue.

Bonnie’s leg would never be the same after the accident. Because the couple had a lot of experience with nursing gunshot wounds, the leg eventually healed, but not properly, since Clyde could not take her to a real doctor. Witnesses described Bonnie as hopping more than walking for the last year of her life, and often Clyde would simply carry her when she had to get somewhere.

Bonnie and Clyde were devoted to their families

Unlike many of their contemporaries in the criminal world, Clyde and Bonnie were not lone wolves depending only on each other and a small group of like-minded criminals. They both had devoted families who stuck by them through their worst times, and they constantly made every effort to stay in touch with and support their relatives.

Bonnie and Clyde made frequent trips back to the West Dallas area, where their families lived, throughout their criminal career. Sometimes they would return for visits multiple times in one month. Clyde’s standard method was to drive quickly past his parents' house and throw a Coke bottle with a note out of his car window; his mother or father would recover the bottle, which contained directions on where to meet outside of town. Although the parents initially didn’t like each other (Bonnie’s mother blamed Clyde for ruining her daughter’s life), they learned to cooperate by speaking in code on the telephone and arranging rendezvous.

When Bonnie and Clyde had money, their families benefited from their largesse; when they were struggling, wounded or destitute, their families helped them with clean clothes and small amounts of money. At the time of his death, Clyde was attempting to purchase land for his mother and father in Louisiana. Eventually, several members of the Barrow family would serve short jail terms for aiding and abetting their famous relatives.

Ironically, Bonnie and Clyde’s devotion to family would be their undoing. Barrow gang member Henry Methvin seemed to share a similar devotion to his family. Clyde and Bonnie took this as evidence of Henry's trustworthiness and did all they could to make sure he saw his own family as often as possible. Henry, however, conspired with his father to betray Bonnie and Clyde by alerting the police to their whereabouts in return for his own pardon. It was on a trip to pick up Henry from his father’s house that Bonnie and Clyde were ambushed.

Bonnie and Clyde were unwilling killers who released more people than they hurt

On the run constantly, Bonnie and Clyde could never rest easy; there was always a chance that someone would become aware of their presence, notify the police, and create the opportunity for bloodshed. This happened over and over through their short and violent career—violent because, once cornered, Clyde would kill anyone in order to avoid capture and a return to prison. Fourteen lawmen died along the way. If it were possible, however, Clyde would more often abduct someone (sometimes a cop), make a getaway, and then release the person somewhere down the line. In more than one instance, he gave the unharmed kidnapped victim money to get back home.

Public opinion turned against Bonnie and Clyde after reports of the murder of two motorcycle cops on Easter Sunday, 1934. Sleeping late in their car near Grapevine, Texas, Bonnie, Clyde and Henry Methvin were taken by surprise by the policemen, who suspected a car of drunks. Clyde’s injunction to Henry to kidnap the cops, “Let’s take them,” was misinterpreted as an encouragement to fire, and Henry blew away patrolman E.B. Wheeler. The situation beyond saving, Clyde fired on the other cop, a rookie named H.D. Murphy, whose first day it was on the job. Murphy was about to get married, and his fiancée wore her wedding gown to the funeral. The public, who had often cheered the brash and brazen outlaws, now wanted to see them caught—alive or dead.

Bonnie and Clyde were difficult to embalm and they knew their embalmer

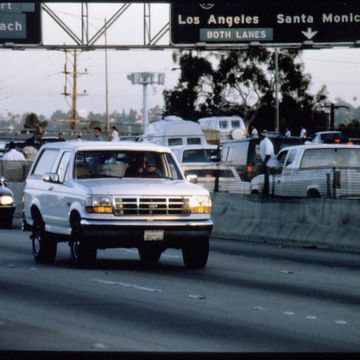

Bonnie and Clyde famously died in a hailstorm of bullets shot at their car by an assembled posse of Texas and Louisiana lawmen. Stopping to help Henry Methvin’s father fix his apparently broken-down truck on a Louisiana road, Clyde pulled the car to a stop when the posse opened fire without warning. Approximately 150 rounds later, Bonnie and Clyde lay dead in their car, which was pockmarked with several holes. Not taking any chances, the leader of the posse, Frank Hamer, even approached the car and fired several additional shots into the already dead Bonnie’s body. Her hand still held part of the half-eaten sandwich that would be her last meal.

The coroner’s report detailed 17 holes in Clyde’s body and 26 holes in Bonnie’s body. Unofficially, there may have been many more. C.B. Bailey, the undertaker assigned to preserve the bodies for the funerals, found that the bodies had so many holes in them in so many different places that it was difficult to keep embalming fluid in them.

Assisting Bailey was a man named Dillard Darby, who had been kidnapped by the Barrow gang a year earlier after his car had been stolen by them and he’d tried to retrieve it. At the time, Bonnie was morbidly tickled to discover that the man they’d kidnapped was an undertaker, and she asked Darby to take care of the gang’s mortuary needs in the future. Little did Clyde and Bonnie know when they gave Darby five dollars and released him that day that he would indeed attend to them after death.

Bonnie liked to write poetry

In school, Bonnie liked to make up songs and stories. She also liked to write poems. Once she was on the run with Clyde, she had plenty of new material to write about. Stewing in jail for a short spell in April 1932, Bonnie wrote ten poems that she grouped as Poetry from Life’s Other Side. They were poems about the lives of criminals and the women who suffered because of them, including “The Story of Suicide Sal,” about a woman who joins a gang and is left to rot in prison by an uncaring man:

Now if he returned to me some time, Tho he hadn’t a penny to give, I’d forget all this “hell” he has caused me, And love him as long as I live.

Bonnie continued to write her poems as the Barrow gang moved towards its inevitable end. Written shortly before her death, the autobiographical poem called “The End of the Line” showed no illusions about her and Clyde’s situation:

They don’t think they’re too smart or desperate, They know the law always wins; They’ve been shot at before, But they do not ignore That death is the wages of sin.

Some day they’ll go down together; And they’ll bury them side by side, To a few it’ll be grief— To the law a relief— But it’s death for Bonnie and Clyde.

Bonnie and Clyde did go down together, her head at rest on his shoulder in their death car, but they were buried separately. Bonnie’s epitaph reads “As the flowers are all made sweeter by the sunshine and the dew, so this old world is made brighter by the lives of folks like you.” Clyde’s reads, simply and accurately enough, “Gone but not forgotten.”