What’s the story?

It’s been called the most contested acronym in Europe, a putative free-trade deal between the world’s two richest trading powers that will either unleash untold prosperity or economic and cultural ruin, depending on your point of view.

The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) is an ugly mouthful, and not just in name. The aim is not just to reduce tariffs between the EU and US but to remove regulatory barriers and standardise rules so that companies can access each other’s market more easily.

It has the potential to be the biggest trade deal ever concluded.

But there are formidable pitfalls and obstacles along the way. Europeans hope the talks, which embark on an eighth round this week after almost two years of deliberation, will result in access to financial services in the US. Washington is resisting.

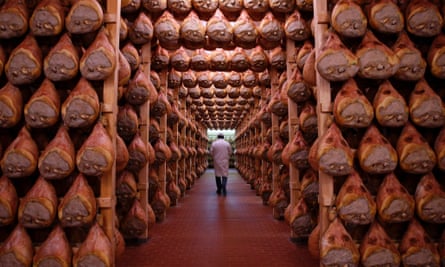

The Americans are eyeing up the food markets that serve the EU’s 500 million mouths. Europeans are concerned this will bring lower US food standards to a continent that prizes its Italian hams and French champagnes.

Above all, public scepticism to the trade accord is spreading across Europe, where growing numbers are suspicious of their political leadership and disenchanted by two decades of globalisation.

How did this happen?

The treaty has been in the works for 12 years, and came about as it became apparent that bigger global trade deals would be hard to achieve. Negotiations started in 2013 and involve at least 100 participants.

The deal would unite the world’s two biggest economies, responsible for 60% of global GDP, in a market of 820 million consumers. For its proponents, it could add as much as 0.5 percentage points to American and European economies, freeing up trade and creating jobs. European car exports to the US could more than double if the right deal is reached, negotiators say. Other industries that stand to benefit include pharmaceutical, energy, clothing and food and drink.

While formally a free-trade pact, the Americans and the Europeans are very much aware that the TTIP is about much more than mere money. Politically and geo-strategically, both sides say that a successfully concluded pact will cement the transatlantic relationship at a time when it has been fraying. Moreover, given the deadlock and the glacial pace of world trade negotiations, the TTIP will create a template for global trade that the big emerging economies, not least China, might feel obliged to follow.

The issues

The biggest problem with TTIP is that the most significant gains are to be made from an area that the public is queasiest about: deregulation. Negotiators know that just removing tariffs is the easy bit – and not worth nearly as much as reforming, reducing and/or harmonising the differing regulations that govern business and industry in the US.

But one person’s regulation is another’s protection, and opponents of TTIP argue that it could threaten consumer protection, social rights, health, the environment and data protection. Some even fret that it could open the door to privatisation by allowing, for example, US health companies to run parts of Britain’s publicly owned National Health Service. The Europeans have already secured the exclusion of audio-visual services to protect the French film industry, a neuralgic issue for leaders in Paris. The question is: will the long list of other exceptions that already include GM food and hormone-fed beef dilute the deal to make it less worthwhile?

An even bigger stumbling block is another clunky acronym, ISDS (Investor State Dispute Settlement), which would allow businesses to sue governments for action that would hurt future profits. Supporters of the bill have argued that ISDS plays an essential role in ensuring smooth transatlantic negotiations. Critics fret that it would bypass national laws and subjugate the interest of governments to those of big business.

Indeed, democratic legitimacy is another big concern. The European public has grown sceptical in recent years of globalisation and the way it puts power and profit into the hands of big business rather than democratically elected leaders. More than 1.3 million people have signed a public petition against TTIP. There are also concerns about the transparency of the negotiations, which have thus far been held in secret with little communication about the exchanges.

Moreover, the deal must be ratified by all 28 government chiefs in the council of ministers, by no means a foregone conclusion: Greece’s new ruling party Syriza has warned it has no intention of approving the pact.

Where can I find out more?

Opponents use the hashtag #stoptafta

For getting to grips with the arguments over potential threats to sovereignty, read Owen Jones in the Guardian on the threat TTIP poses to democracy

The Guardian’s Brussels correspondent Ian Traynor tweets at @traynorbrussels and has written on European divisions over TTIP

Policy experts at the thinktank European Council on Foreign Relations have put together a proposed compromise on the deal

The EU trade negotiating team tweet at @EU_TTIP_team

The EU published its initial TTIP position papers here and its negotiating texts here