UPDATE 2 (Feb. 3, 4:40 pm): This story has been updated to include the presence of Jonathan Burkan at the Jeb Bush dinner.

UPDATE 1 (Feb. 3, 9:30 am): This story has been updated to include the presence of Jerry Langer at the Jeb Bush dinner.

This morning, The New York Times will hit doorsteps with a front-page take-down detailing Chris Christie’s “Fondness for Luxe Benefits When Others Pay the Bills.” Parties with Bono at King Abdullah’s palace and $30,000 hotel bills cannot be expected to play well in Iowa, where last night a new Des Moines Register poll showed Mr. Christie tied for eighth place with the support of only 4 percent of Republican caucus goers.

Three years ago, Mr. Christie was begged by a Republican establishment dismayed at a weak field of candidates to run for president. Today, amid what many consider the strongest field the GOP has offered in years, even some of Mr. Christie’s most loyal supporters are looking elsewhere. To understand how we got from there to here, one has to understand how Mr. Christie got from there to here.

If Chris Christie becomes the President of the United States, people wanting to visit the house he came home to as a newborn in 1962 will find neither a rustic cabin nor a rolling estate. Instead, they would confront a bracing cityscape typical of American urban reality.

The starting point of Chris Christie’s American Dream was in Newark, although the landscape has changed much since the time he lived here.

|

Mr. Christie’s old Newark neighborhood, in the shadow of West Side High School, is a snapshot of the struggling city so many former Newarkers left behind as part of the “white flight” to the suburbs that the Christie family joined in 1967 when they too fled, to leafy Livingston in Western Essex County.

At the corner of South Orange Avenue and South 14th Street, one three-story building facing the high school stands vacant, its windows rimmed by craggy, shattered glass, a lone, leftover curtain flickering in a permanently open window. Around the corner, across a muddy lot littered with empty single-serving liquor bottles and an abandoned couch, one man, a cigarette dangling from his lip, checks all the doors in the middle of the day. Whether he is acting as neighborhood watchman, or seeking an opportunity for something less wholesome is unclear. At the same time, a few doors down from a boarded-up house, another is getting fixed up, its neat ivy-covered trellis a testament to hard work and hope.

The starting point of Chris Christie’s American Dream was here, although the landscape has changed much since the time he lived here. His road toward its realization, and how it shaped Mr. Christie’s politics and policies, will be more closely scrutinized as he stands on the brink of a run for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination.

The particulars of Mr. Christie’s life can be framed in ways familiar from both literary fiction and TV pop culture.

Fictitious mob boss Tony Soprano, for instance, was born in Newark, moved with his family to the near suburbs of Essex County, and then to the Caldwells as he rose up through mafia middle management. The stories of Pulitzer Prize-winning author Philip Roth, a Newark native, depict several American Jewish characters that left his hometown, seeking brighter horizons in places like Short Hills and further west.

Three important chapters in the arc of Mr. Christie’s story are similarly set. He was born and spent his earliest years in Newark, spent the rest of his childhood in nearby Livingston, and eventually moved to Morris County’s Mendham, as his professional success grew and his political career blossomed. Any reader interested in the tale of Mr. Christie’s life, one that soon could see a presidential campaign chapter, wants to know which one contains the theme most revelatory to the story’s final outcome.

The neighborhood Mr. Christie lived in as a young child was nothing like it is today. New Jersey State Assemblyman Tom Giblin was raised in Newark, and he remembered it in the early 1960s as an Italian-Irish working-class enclave.

“The neighborhood wasn’t a crime-ridden area. People were looking for their kids to get into public service—the police department, fire department, municipal government, the Board of Education. The emphasis was not on getting into college to the degree it was later on,” said Mr. Giblin, 67, himself having fled Newark for the suburbs of Western Essex County before running for the Assembly against the incumbent—a Livingston guy called Tom Kean. “A lot of kids were vocational school graduates, and they got jobs in the union trades. It was a way to security.”

Today, the neighborhood in Newark’s West Ward is considerably less secure, plagued by a high crime rate, including many of the more than 90 homicides committed in the city in 2014. Newark’s unemployment rate lingers at just under 11 percent, considerably higher than the state’s 6.5 percent rate, according to September 2014 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Christies would leave Newark for Livingston in 1967, when Chris was 5 years old, just before a cocktail of economic, political and racial tensions led Newark to explode in that summer’s civil disturbances that scarred Newark in ways still felt. According to Robert Curvin, a senior policy fellow at the Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University, former vice-president of the Ford Foundation, longtime Newark resident and author of Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation, a troubled school system was a critical accelerating factor in Newark’s decline.

“If you don’t have good schools, you’re not going to keep your people,” Mr. Curvin said, citing detrimental patronage-based hiring in Newark’s schools during the administration of Mayor Hugh Addonizio, who was convicted on federal corruption charges in 1970. “[The movement to the suburbs] changed industrial cities across the entire country. Growth was almost like a religion, and to build the suburbs was almost like a grand mission. Whether or not the demographics had to turn out the way that they did is another question. It could have been different.”

Referring to the state of public education, in the book Chris Christie: The Inside Story of his Rise to Power by reporters Bob Ingle and Michael Symons of The Asbury Park Press, Mr. Christie would note that his parents’ decision to leave Newark played a key role in his future career. “I don’t think I’d be governor,” Mr. Christie said.

Mr. Christie is the product of suburban public schools, but prompted by either principle or politics, he has not lost sight of the needs of urban schools. Mr. Christie stood with then-Newark mayor and current U.S. Sen. Cory Booker, D-NJ, and Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg in 2010 when the social media titan pledged $100 million to revamp Newark’s schools, which were placed under state control in 1995. It is unclear whether the dramatic attempt to jump-start school reform in Newark has had any lasting effect.

![cjclhs1980[1]](https://observer-media.go-vip.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/02/cjclhs19801.jpg?w=138) Mr. Christie’s decision to appoint Cami Anderson to head Newark’s public schools in 2011 has created what many see as an educational impasse, especially after Ms. Anderson launched her school reorganization scheme, known as the “One Newark” plan, in September. Meant to improve the city’s public education system by increasing student options, the plan has left many parents angry, confused and frustrated. A widespread community backlash included vociferous student, parental and teacher protests. Prominent local politicians also spoke out, including state Senate education committee chair Teresa Ruiz, who stated that “the trust is gone” in Ms. Anderson’s leadership of the city’s schools. Yet Mr. Christie doubled down on his support for Ms. Anderson and her plan, renewing her contract for three more years in June.

Mr. Christie’s decision to appoint Cami Anderson to head Newark’s public schools in 2011 has created what many see as an educational impasse, especially after Ms. Anderson launched her school reorganization scheme, known as the “One Newark” plan, in September. Meant to improve the city’s public education system by increasing student options, the plan has left many parents angry, confused and frustrated. A widespread community backlash included vociferous student, parental and teacher protests. Prominent local politicians also spoke out, including state Senate education committee chair Teresa Ruiz, who stated that “the trust is gone” in Ms. Anderson’s leadership of the city’s schools. Yet Mr. Christie doubled down on his support for Ms. Anderson and her plan, renewing her contract for three more years in June.

Mr. Christie’s fundamental belief that New Jersey’s urban schools can do better by their children is rooted in his support for charter schools and one in particular, The Robert Treat Academy. Founded by Stephen N. Adubato Sr. in 1997, Robert Treat is one of the highest performing schools in New Jersey, public or charter.

Unlike Mr. Christie’s parents, Mr. Adubato did not flee Newark for the suburbs after the 1967 riots. Instead, the passionate and at times provocative Mr. Adubato, who hung prints of Machiavelli in his office, built his North Ward Center, begun in 1970, into a non-profit powerhouse and a political power base whose influence extends beyond the center’s neighborhood. The center, its headquarters in a citadel-like 19th-century mansion, runs a pre-school, a job-training and language-training center, an adult medical day care center and youth recreation programs.

Mr. Adubato achieved this success by embracing his new neighbors when they changed from Italian to Latino. And while never holding elected office, Mr. Adubato held the reins of a classic, urban Democratic political machine that rewarded his allies and punished his enemies, with a ferocious get-out-the-vote machine always remembering those politicians, especially in primary races, who helped his social services programs (and punishing those who failed to do so).

One sure sign of this quid pro quo relationship: The day after his victory in the 2009 gubernatorial election, Mr. Christie himself arrived at the Robert Treat Academy and paid tribute to Mr. Adubato’s influence.

“As I traveled all around the state, campaigning for governor there was only one school I talked about more than any other school in New Jersey,” Mr. Christie told the students. “I wanted for every child in the state to get an education like all of you are getting.”

Mr. Christie told a gaggle of news cameras that morning that Robert Treat set an example for other public schools.

“It is not as if we are walking around in a dark room saying I wish we could just find the light switch,” Mr. Christie said. “The light switch is on. It’s here.”

Mr. Adubato, 82 and in declining health, no longer does interviews. But Joe Parlavecchio, a fellow political power broker from Newark’s Ironbound neighborhood, spoke to what the power of local organization ability can achieve.

“He knew the demographics were changing. He didn’t resist it. He embraced it,” said Mr. Parlavecchio, who has known Mr. Adubato for 45 years. “I don’t want to say that you can only amass power the way Steve did, when you can do it the elected way, the way Gov. Christie did. But all politics is local. And Steve understood that.”

After Mr. Christie’s family left Newark, Mr. Christie lived the life of a typical suburban kid of the 1970s growing up in the upper-middle-class suburbs west of New York City, a kid who loved baseball (he’s a lifelong Mets fan), rooting for the Dallas Cowboys and listening to Bruce Springsteen.

Mr. Christie’s childhood home on West Northfield Road in Livingston sits amid modest Cape Cods in the type of post-war suburban neighborhood that could be anywhere in America. It is easily accessible to Newark on Interstate 280, a road completed in the early 1970s when middle-class families left New Jersey’s largest city in droves. With no train station and no single downtown, Livingston’s nearly 30,000 residents are spread out in a type of suburban sprawl that typifies the kind of development that defines much of New Jersey.

A wide, grassy oval stretches in front of the neo-colonial Livingston High School, where Mr. Christie graduated in 1980. The school was a hotbed of high achievers during that period—in addition to the future governor, actor Jason Alexander, White House advisor Alan Krueger, and best-selling author Harlan Coben, who remains close to the governor today, all patrolled the LHS hallways. Livingston in the late ’70s displayed a clear divide between middle class and rich. Just as the Livingston Mall, which opened in 1972 with famous-in-Newark retailers like Bamberger’s, M. Epstein, and Hahne & Company, was trying to compete with the Short Hills Mall down the street, working-class Livingston gathered at places like The Landmark, a humble watering hole that makes frequent appearances in Mr. Coben’s books. In a town where opulence was often on display, the Christie family had less, which surely fed the ambitions of the family’s eldest child.

A wide, grassy oval stretches in front of the neo-colonial Livingston High School, where Mr. Christie graduated in 1980. The school was a hotbed of high achievers during that period—in addition to the future governor, actor Jason Alexander, White House advisor Alan Krueger, and best-selling author Harlan Coben, who remains close to the governor today, all patrolled the LHS hallways. Livingston in the late ’70s displayed a clear divide between middle class and rich. Just as the Livingston Mall, which opened in 1972 with famous-in-Newark retailers like Bamberger’s, M. Epstein, and Hahne & Company, was trying to compete with the Short Hills Mall down the street, working-class Livingston gathered at places like The Landmark, a humble watering hole that makes frequent appearances in Mr. Coben’s books. In a town where opulence was often on display, the Christie family had less, which surely fed the ambitions of the family’s eldest child.

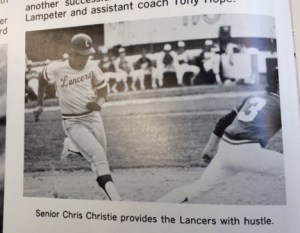

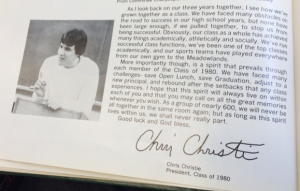

In his senior yearbook, Mr. Christie can be seen playing for the baseball team and is listed as president of his senior class. His black-and-white senior class headshot, one among hundreds with mostly Italian, Irish and Jewish last names, seems muted compared to the colorful politician who later emerged.

At the same time, some glimmers of the adult Mr. Christie were evident during his adolescence. The future governor believed in private enterprise. At Cammarata’s Pizza Pantry, Mr. Christie worked behind the counter, delivered pizzas and did whatever else needed to be done to support the small business. In Livingston, you were either a Cammarata’s guy or a Bonvini’s guy. As we’ve seen with the Dallas Cowboys, the governor is someone who picks a team and sticks with it.

“Livingston has changed a lot. It’s a lot more affluent. We cater to mostly blue-collar guys, the cops, the firemen,” said Cammarata’s owner Dana Stefanelli, 47, as the pizzeria’s ovens produced thick, steaming pies. “Our families came at the time of the riots in Newark, and this was the place to come. The first generation came off the boat and stayed in Newark. Then the second generation moved up here to provide a better life for their family. Then the next generation moves further out. I think politicians are full of crap, but Mr. Christie was a working-class, middle-class kid. He worked.”

Across town at Jay’s Shoe Box, a little girl runs the length of the store wearing one pink boot and one silver boot before her mother tells her to pick one or the other. Owner Ted Wickner remembered that Mr. Christie used to help kids pick out shoes when he worked there.

“He was a high school kid who needed a job, so we gave him a job,” said Mr. Wickner, 56, whose family has run the store for about 60 years. “People today are more aware about your economic situation. Years ago, people here didn’t care about what car you drove and how big your refrigerator was. We still have a six o’clock whistle. When we were kids, we knew that meant it was time to run home and go eat dinner. There were no fences in anybody’s backyard. Our parents weren’t micro-managing us. No one was micro-managing us. We took care of ourselves.”

“He was a high school kid who needed a job, so we gave him a job,” said Mr. Wickner, 56, whose family has run the store for about 60 years. “People today are more aware about your economic situation. Years ago, people here didn’t care about what car you drove and how big your refrigerator was. We still have a six o’clock whistle. When we were kids, we knew that meant it was time to run home and go eat dinner. There were no fences in anybody’s backyard. Our parents weren’t micro-managing us. No one was micro-managing us. We took care of ourselves.”

Chris Christie’s political interests gelled in high school. While Livingston symbolizes suburban sprawl in many ways, pockets of patricians still lived in town while Mr. Christie was growing up. The future 55th governor of New Jersey knocked on the front door of the Livingston estate of the man who would become the state’s 48th governor, Tom Kean, to volunteer for Mr. Kean’s first gubernatorial campaign in 1977.

In May of that year, five LHS students met at Livingston High School early on a Saturday morning. They drove to a Republican State Committee event at the War Memorial Building in Trenton—two seniors in the front seat and three lower classmen in the back. One of those in the backseat was Mr. Christie; another was David Wildstein, the friend of the future governor who would later be appointed by him to a position at the Port Authority, where he would play a role in the Fort Lee Bridge Scandal bedeviling the governor. (Mr. Wildstein is also the founder of the Observer‘s sister site, PolitickerNJ.) All four gubernatorial candidates spoke and the LHS boys supported their hometown hero, handing out Styrofoam hats with “Byrned Up? Let’s Raise Kean” bumper stickers on them, referring to Brendan Byrne, who won re-election despite the boys’ best efforts. On the way back to Livingston, the seniors stopped to buy beer. It was Mr. Christie’s first political rally and also his first beer. He was 14.

According to Don Schwartz, a now-retired photography teacher at Livingston High School, a class trip to Washington, D.C., left him transfixed. “Chris took many pictures of the government buildings—the White House, the Capitol and so on,” remembered Mr. Schwartz, 70, who was Mr. Christie’s class adviser during his senior year. “He processed the pictures in the dark room when we got back and he made the prints. I guess something caught his eye.

“When he was the starting catcher on the school baseball team, there was a transfer student who came in during his senior year who beat him out,” Mr. Schwartz added. “Many athletes would go to the bench and just retreat. But Chris didn’t do that. He was supportive and enthusiastic, and the team went on to win the state championship. Above all, Chris always wanted to win.” That transfer student, by the way, was Marty Writt; the son of a Livingston cop, Mr. Writt was drafted by the Cleveland Indians.

After high school, Mr. Christie channeled his ambition at the University of Delaware and Seton Hall Law School. He married his wife, Mary Pat, began his family of four children, settled in at a private law firm, Dughi & Hewitt, and made partner. After buying a starter home in Cranford, the Christies moved farther to the west, just past Morristown to Mendham.

Mr. Christie didn’t pick Mendham by accident. The city of his birth was out of the question for a Republican aspirant, and even leafy Livingston, with its growing numbers of socially liberal Jews and labor-friendly Catholics would be tough. As newlyweds, the Christies had first lived in a starter apartment in Summit and then a home in Cranford, but those posh suburbs sit in the aptly named Union County, another Democratic stronghold. Off to Mendham, in highly Republican Morris County, the Christies headed.

A nuance of New Jersey politics bears explaining here. In most New Jersey counties, the county party awards the line on which its favored candidate sits on the ballot. That position invariably goes to the incumbent, which makes it almost impossible to defeat him—that’s what keeps the county bosses powerful. So it’s become “uncouth” in New Jersey to challenge incumbents from one’s own party and those who do are thought of as cowboys and malcontents. But Morris is one of only two counties in the state that doesn’t award a line—the perfect home for an ambitious politician who puts personal goals above party harmony.

It was after he moved to Mendham that Mr. Christie launched his political career. It didn’t go so well. In 1993, the young lawyer tried to primary his fellow Republican, Senate Majority Leader John Dorsey—Mr. Christie was kicked off the ballot for lacking the required signatures. The next year, he joined an insurgent slate for freeholder—N.J.’s equivalent to “county commissioner.” It was an exceptionally nasty race, even by New Jersey’s low standards. Mr. Christie’s rivals filed defamation lawsuits against him; in his next freeholder election, he sued his opponents. The Star-Ledger concluded that Mr. Christie was “remembered for his political ambitions and angry conflicts” in an “early political career [that] was marked more by bitter campaigns than by policy initiatives.”

Bitter and ambitious is right. Three months after winning that first freeholder bid in 1994, Mr. Christie ran for State Assembly, again primarying Republican incumbents. Mr. Christie and his running mate (Assemblymen run in pairs) were lampooned as the “millionaire ticket” and one particularly nasty mailer caricatured Mr. Christie in diapers throwing a tantrum. Mr. Christie and his running mate lost—Mr. Christie was the low vote-getter of the four major candidates and then Mr. Christie lost his re-election bid for freeholder, coming in dead last.

It seemed as though Mr. Christie’s career as a candidate was finished. He resumed his full-time legal career, drawing closer to Dughi & Hewitt partner Bill Palatucci, who became and would remain Mr. Christie’s advisor and much-feared fixer. After raising money for George W. Bush in the 2000 presidential campaign, Mr. Christie was appointed U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey, a position he held from 2002 to 2008.

Champions could call Chris Christie’s personal story a pattern of effort, critics one of expediency. But if Mr. Christie wants to finally burst from the backstage into the Oval Office, there could soon be a reckoning regarding one result of that constant drive for the next best thing: His record as New Jersey’s governor.

|

New Jersey, which has close to 9 million residents, is the most populous state to have just one U.S. attorney. At the time Mr. Christie served in the already powerful position, New Jersey had no statewide elected office besides governor (excluding senators, who of course serve outside of the state), such as lieutenant governor, that could even come close to rivaling its influence. Mr. Christie’s appointment was controversial in the legal community because he was a corporate lawyer and lobbyist with no criminal or trial experience. Still, he beat out formidable candidates like John Peter Suarez, the director of gaming enforcement, Attorney General John Farmer, and Rosemary Alito, the sister of future Supreme Court Justice (and another Christie predecessor as NJ USA) Samuel Alito. Some speculated at the time that Mr. Christie made a side deal with then-Sen. Robert Torricell, who along with Sen. Jon Corzine (himself later to be defeated by Mr. Christie) agreed not to stand in the way of President Bush’s choice.

Mr. Christie used this unique legal bully pulpit to generate a reputation for corruption-busting that built his statewide stature, a platform he used to propel himself to victory over Democrat Mr. Corzine in the 2009 gubernatorial election. Yet Mr. Christie’s high conviction rate of more than 100 public officials in a state that has a reputation of having a gift for graft was not without controversy. While Mr. Christie took down important politicos such as a Democratic State Senate president and a Republican county executive, critics pointed to those who escaped his full fury. During his tenure as U.S. attorney, Mr. Christie authorized seven deferred prosecution agreements.

It helped to be Mr. Christie’s friend.

During his tenure as U.S. attorney, Mr. Christie authorized seven deferred prosecution agreements, including one that required pharmaceutical company Bristol-Myers Squibb to endow a business ethics chair at Seton Hall Law School, Mr. Christie’s alma mater. In the case of Zimmer Holdings, Mr. Christie recommended that former Attorney General John Ashcroft—i.e., Mr. Christie’s former boss—receive the outside monitor contract worth as much as $52 million. In another DPA, Mr. Christie appointed the former U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, David Kelley, to oversee Biomet Orthopedics Inc., a medical supply companies accused of paying kickbacks to doctors who used their products. The appointment raised eyebrows—the Philadelphia Inquirer declared “Poor judgment has tarnished the former prosecutor’s reputation”—because Mr. Kelley’s office had investigated Todd Christie in a stock-fraud that resulted in charges against several others but not in charges against the governor’s younger brother. The decision was made to not prosecute him.

Then there was Herbert Stern, Mr. Christie’s friend and mentor, as well as his predecessor as New Jersey U.S. attorney. As the Observer reported in a profile last year, Mr. Christie’s 2005 investigation of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, one of the largest medical schools in the country, revealed it to be a “veritable parking garage for politically connected no-show jobs,” with prominent New Jersey politicians placing brother-in-law types in lucrative positions. Mr. Stern’s firm, Stern & Kilcullen, became the monitor of the UMDNJ’s deferred prosecution agreement, earning at least $3 million for its efforts. The lead Stern & Kilcullen monitor performing the work was John Inglesino, Mr. Christie’s longtime friend and like Mr. Christie, a former Morris County freeholder. Meanwhile, according to New Jersey’s Election Law Enforcement Commission, Mssrs. Stern, Kilcullen, Inglesino and their wives contributed nearly $24,000 to Mr. Christie’s 2009 bid for governor.

Mr. Christie’s Republican slate mate at the time of that first Assembly run, Richard Merkt, is not surprised by Mr. Christie’s continuing ambitions.

“In my view, he was exactly who he was then as he is now,” said Mr. Merkt, 65, of Mendham, who eventually served in the Assembly from 1998 to 2010. “I believe that the guiding principle in his political career has been what will advance his political interest. Mendham was a prestigious place for him to hang his hat. I don’t think he’s ever changed from being an Essex County guy. His style, his gestalt, certainly didn’t change when he came to Mendham. He was obviously a man in a hurry. I think I remember him saying something like ‘I’ve accomplished what I wanted to accomplish as a freeholder’ when he said he was running for the Assembly, and that said it all. We both got shellacked. The next time I ran, my wife said, ‘You better run alone.’ ”

“The interesting thing is that I don’t recall even reading anything written by him,” added Mr. Merkt, who competed against Mr. Christie in the 2009 GOP New Jersey gubernatorial primary. “Most of us in political life at some point write books or articles. First, I don’t think he’s ever liked the idea of a written record. Second, I think he much prefers media that allow him to control the situation. Sound bites are great for him, and he’s extremely talented at them.”

A trip to the Mendhams (it is comprised of both a township and a borough) is a journey back to the state’s rural Colonial heritage. The borough’s Main Street has white clapboard buildings in the center of town. The more than 100-year-old post office in the Brookside section of the township, across the street from where Mr. Christie votes, could easily be the backdrop of a Norman Rockwell painting. Signs advertising doll fashions and dog walkers, and seeking drivers and cleaning ladies, hint at the disposable income available in town. Somewhat incongruously, a portrait of U.S. Army Gen. George Patton is tacked up on the post office’s community bulletin board. Then again, many homes in the area, including the Christie house on top of a hill, seem fit for a multi-starred general. By any measure, making it to Mendham seems to signify that you have “made it” in general.

Mr. Christie’s move to Mendham was not completely a self-driven Horatio Alger story. Mary Pat Christie’s success working on Wall Street helped provide the funds needed to build a lifestyle far from the governor’s working-class roots. The governor’s brother, Todd Christie, has also done well in the financial services industry, and he has been a big financial backer of Republican candidates. The Christie brothers together raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for George W. Bush’s 2000 presidential campaign.

Whether or not Mr. Christie gets to affect all of America depends on whether or not he gets through the 2016 GOP primaries, with tough potential challengers such as former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, U.S. Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky and U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas waiting in the wings.

The aforementioned anecdotes from Mr. Christie’s life and background show someone driven to succeed. Champions could call his personal story a pattern of effort, critics one of expediency. But if Mr. Christie wants to finally burst from the backstage into the Oval Office, there could soon be a reckoning regarding one result of that constant drive for the next best thing: His record as New Jersey’s governor.

Mr. Christie’s poll numbers have dipped in recent months in part because he has spent a large amount of time out of state over the past year, both as the Republican Governors Association chairman and as a presidential hopeful who is building up a national network. There are considerable concerns mounting in New Jerseyans’ minds as of late. The state and federal investigations focused on the shutting down of access lanes to the George Washington Bridge, also known as Bridgegate; a sluggish state job recovery following the recession; successive downgrades of New Jersey’s credit rating by rating agencies; questions about the distribution of post-Hurricane Sandy aid; an ongoing downward spiral of Atlantic City casino closures; and a reversal on his signature pension reform agreement with public employees, saying that the state could not afford to make the pension payments required by the accord—all of it has led New Jerseyans to increasingly question Mr. Christie’s leadership. And as New Jersey’s property tax rate, the highest in the nation, remains the state’s bête noire, Garden State residents are increasingly choosing not to stay, with half saying that they want to move, according to the Monmouth University Polling Institute.

While Mr. Christie touted the progress of the South Jersey city of Camden in his recent State of the State address, a speech laced with national ambition, there is no end in sight to the turmoil in Newark’s schools. One week before his speech, a state legislative committee, cheered on by some Newarkers who made the trip to Trenton to watch, excoriated Cami Anderson’s leadership of the city’s schools. Mr. Christie might have shined a flashlight on Camden in front of a national audience. But it seems like he stopped looking for that light switch he mentioned in Newark the day after he was elected governor.

Mr. Christie is definitely looking for money: In January, he announced the formation of his political action committee geared toward a 2016 presidential run. The fight for funds among the Republican donor class is expected to be fierce, even in Mr. Christie’s home state. Lawrence E. Bathgate, a prominent New Jersey attorney who served as the Republican National Committee’s finance chairman under Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, has become a vocal critic of the governor, in a way that was unimaginable before Bridge Gate, when Mr. Christie’s people demanded—and received from all major GOP players—that anyone who wanted a future in the state sing off the same Chris Christie song sheet. Mr. Bathgate has called the governor’s post-Sandy reconstruction policies “stupid” and said his plan for sand dunes violated Republican doctrines of property rights and limited government.

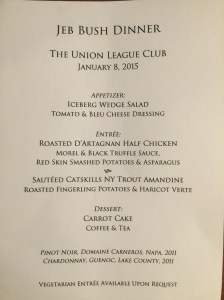

Mr. Bathgate has done more than take pot shots. On January 8, he convened a dozen or so New Jersey and New York financial heavyweights. The menu consisted of roasted D’Artagnan half chicken or Sauteed Catskills NY trout Amandine and … Jeb Bush. The Observer is the first to report that the group addressed by the former governor of Florida included not just Mr. Bathgate, but Gail Gordon, who had been on Mr. Christie’s finance committee; former Mercer County Executive Bob Prunetti; Domenic DiPiero, founder of Newport Capital; Jerry Langer of Langer Transport, who had served on Mr. Christie’s transition team; Tom Gallagher from Princeton, who’s the CEO of Miami International Holdings; Monmouth County power lawyer Brian Nelson; former head of the Republican Jewish Coalition Cheryl Halpern; and the Minority Leader of the State Senate Tom Kean, Jr. (Despite Mr. Christie’s friendship with Mr. Kean’s father, the former governor, Mr. Christie tried to depose the younger Kean in a ham-fisted coup attempt that failed). The group was joined by a few non-New Jersey finance bigs as well, including Former Ambassador to Belgium Bruce Gelb; John Sargent (the son-in-law of Brenda LaGrange Johnson, who was ambassador to Jamaica); Theresa Kostrzewa, a Romney donor from North Carolina who had already jumped ship to Jeb; NYC-based UBS wealth manager Jonathan Burkan; plus longtime Bush family finance hand Jack Oliver.

Those not from places nicknamed “The Soprano State” might not comprehend how shocking it is that a group of this weight gathered in support of someone other than the state’s leader. But consider that in 2012, when Mr. Christie had yet to declare which GOP candidate he’d be supporting, all 21 of the 21 GOP county chairmen also withheld their endorsements until the leader was ready and then all 21 joined him in supporting Mitt Romney. At the time, one backer of Rick Perry said he’d never seen anything like it, where an entire state party’s apparatus was brought to bear behind its leader. So the idea that a room could be convened with high-profile donors in support of someone who’s actually going to be opposing Mr. Christie is stunning.

Perhaps most surprisingly of all, the group also included State Senator Joe Kyrillos. The presence of Mr. Kyrillos at the dinner sent shockwaves throughout the state’s GOP. A former state chairman, Mr. Kyrillos has ties to Jeb Bush, who headlined the NJ GOP gala in 2003 and did an event for Mr. Kyrillos’ U.S. Senate campaign in 2012. But that cannot compare to the Christie-Kyrillos friendship. Twenty years ago, the governor introduced Mr. Kyrillos to his wife, Susan. Mr. Kyrillos, who is respected throughout the state and wildly popular in his Monmouth County district, served as chairman of the governor’s 2009 run and even swore him in when he won his first freeholder race in 1995. As The Star-Ledger put it, “Kyrillos’s attendance is particularly notable given his long and deep personal relationship with the governor.”

With New Jersey donors and elected officials suddenly displaying an independent streak, Mr. Merkt commented on the New Jersey governor’s bid to play in the big leagues.

“Be careful what you wish for,” Mr. Merkt said. “There are many things that happen in New Jersey that you can get away with because of the state’s political culture, and because New Jersey is in somewhat of a media vacuum, dominated by New York City and Philadelphia in its northern and southern halves. I think the rules change dramatically when you step into the presidential arena and are subject to a much greater level of scrutiny.”

Just this week, we saw an example of a candidate who might not be ready for the national stage just yet. Against a backdrop of an outbreak of measles at Disneyland, the governor was asked about vaccinations while on a three-day junket to England to bolster his foreign policy credentials. He replied that parents “need to have some measure of choice” about vaccinating their children, a reply widely seen as pandering to the anti-science right wing of the GOP in a way very much at odds with his pragmatic persona. The media pounced, with the WaPo’s blogger-in-chief Chris Cillizza writing, “When you are running to be the leader of the country, you can’t get away with saying things like this.”

Inside Mendham’s Black Horse Pub, where Mr. Christie often goes with his family, people are taking a pause from the winter’s cold. Sitting at the bar is Bob Sponheimer, who has made a trip in life similar to Mr. Christie. Born near the Grand Concourse in the Bronx and raised in Teaneck, Mr. Sponheimer began a career in finance and settled down in Summit, another affluent suburban town not far from Mendham. But the journey to the suburbs, unlike many of his neighbors, didn’t convince him to switch from Democrat to Republican.

“It’s the Bronx in me. The only one in my family who didn’t vote for FDR was my grandmother because he drafted her son,” said Mr. Sponheimer, 74. “The attitude out here, what changes people, is that they have it, and they don’t want anybody else to have it. As you become more accomplished, you get hit left and right about taxes and where they are going. A lot of people think it’s ‘them,’ and they’re the ones who are hurting us. The truth is a hell of a lot more complicated than that. But nobody looks at nuances anymore.”

The poet Robert Frost told JFK just before his inauguration to “be more Irish than Harvard,” a reminder of immigrant, urban toughness as a guiding force more powerful than elitism. For Mr. Sponheimer, if Chris Christie wants to be president, he has to make another choice, one that calls him back to his earliest home.

“He’s got to be less Jersey. He should be somewhat Newark, but without all of the gruffness,” Mr. Sponheimer said. “Christie is a political animal, and he’s good at it. Sometimes I like him, other times I don’t know where he’s coming from. If he could be part of that working-class identity, he could do well. He’s a tough Jersey guy who has to learn how to relate to Middle America.”

Mark Bonamo is the senior reporter at PolitickerNJ. The Washington Post recently included Bonamo on its list of “best state political reporters.”